Beyond the Classroom and the Cell: An Interview with Marc Lamont Hill

Beyondthe Classroom and the Cell: An Interview with Marc Lamont Hill byDavid J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

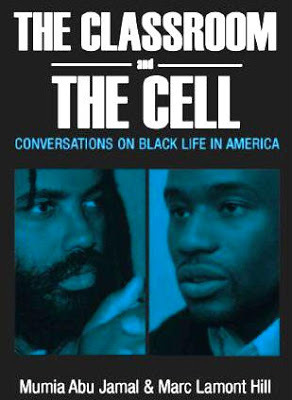

MarcLamont Hill and Mumia Abu-Jamal are two of the most visible intellectuals of mygeneration. Separated by the wallsof injustice, The Classroom and the Cell:Conversations on Black Life in America brings these two giants in thestruggle for justice together.

Discussing family, life and death,hip-hop, love, politics, incarceration and so much more, this book highlightstheir prominence and passion in the fight to "make America again." As Susan L. Taylor describes in herendorsement of the book: It "gives voice to what is rarely heard: AfricanAmerican men speaking for themselves without barriers or filters, about themany forces in their lives." Inspiring and illuminating, informative and insightful, The Classroom and the Cell: Conversations onBlack Life in America is a conversation about issues and about theseprominent figures. Amazing as thebook is, I had the opportunity to talk to Marc Lamont Hill to discuss the bookand its power.

David J. Leonard: How did the book come about?

Marc Lamont Hill: The book really emerged naturally out of myrelationship with Mumia. I havebeen working on his defense, advocating for him for years, but it was in 2008when we actually started a direct personal relationship. He called me out of the blue, right inthe middle of the Democratic primaries, and we talked. He reached out and told me that he readmy work and that he had seen me on TV; he appreciated the work. It was all love so we rapped about thework; we talked about Obama, we talked about whether or not he could beatHilary Clinton and that almost became the source of our weeklyconversations.

Hewould hit me every Friday at 5:30. We would just talk and as we began to talk more we developed a critiqueof Obama and what it meant for him to become President. We also talked about our lives, aboutour children, and about the other intellectual interests we had; we talkedabout culture and so much other stuff that we developed a bond and friendshipthat continues until now. After awhile, we said lets do some work together.

Initiallywe thought we would write a book, a more traditional book on black life inAmerica. It was an interestingproject. We started to writeessays together and the thing that we noticed was that we were melding ourvoices into one; we were losing our distinctiveness, we were losing the thingthat made our conversations so rich: we had similar politics, we had similarvalues, but we also different perspectives, we came from very different places,we occupy very different social locations.

Wedecided that instead of trying to transform these conversations into somethingelse we would spotlight the conversations in the tradition of CornelWest and bell hooks, and JamesBaldwin and Margaret Mead.

Wedecided to do a book of conversations, talking about the things that matter tous, the stuff that we care about. Politics came up, issues of life of death, leadership, education, loveand relationships. Over the courseof a year, we talked every Friday at 5:30 and that became the basis of many ofthe chapters in the book. Betweenprison visits, letter writing and phone conversations we produced this book,which I hope reflects the depth and breadth of our conversations as well was thedeep love, commitment and respect we have for each other

DJL: When I was reading I was thinking about theWest-hooks and Baldwin-Mead dialogues of the past, but this book felt differentbecause of the level of respect and the love between the two of you; it felt moreintimate than what we often get with dialogues and discussions between twoprominent public figures. You givereaders not only your assessment about the world, but also insight aboutyourselves.

MLH: That is what we wanted to do. We have each writtena lot; we each occupy public lives and because of that, certain parts of who weare get exposed all the time; our ideas, our perspectives, our ideologies allget revealed. But we wanted tolocate ourselves in this work. We wanted to give more perspective on who arewe, but we really wanted to go deeper, to show who we are, to expose our anxietiesand fears; we wanted to link the ideas to our personal stories. We wanted to tell a different story andwe also wanted people to know that people conversing in this book are peoplewho care deeply for each other and can model a kind of love ethic necessary forsocial change. It shouldfeel more personal because it was.

DJL: I thought the chapter on lovewas very powerful. It brought theentire book together, because the conversations and the book itself seem tocome from not just the love and respect you have for each other, but also thelove and respect you both have for the issues, the communities, and the voicesand histories so often unloved and disrespected. I thought it was a powerful way to anchor the book, asit is a living example of the power of that love ethic

MLH: We hope so. That was our goal. This isthe stuff that moves us. This isthe stuff that wakes us up in the morning; the ideas we wrestle with everysingle day. The love chapter inmany ways anchors the book because that is what this is all about: a profoundlove for each other, a profound love for our people, and people everywhere. We hope the book puts a spotlight on theissues that matter most to the people who have the greatest need. We hopefully we can then link that tochange, to social transformation. But it all comes back to love. We are trying to model a different level of love, to explore that levelsince we don't have the answers since we are wrestling and struggling with thisstuff as much as anyone else. Weare willing to do that in public and that takes an ethic of risk that will payoff in the end.

DJL: Indeed. As opposed to essays, the conversational approach allows you to wrestlewith those larger issues, going back and forth, reflecting on the complexityand contradictions, revealing that vulnerability so uncommon amongstintellectuals, public figures, and politicians. We are so often trying to prove that we have theanswers. The conversationshighlight the exploration, self-reflection, and vulnerability.

MLH: That is what it is all about. We live in as society where its not OKto wrestle with anything, where it is not OK to have contradictions, where itis not OK to change your mind. Think how we beat up on political candidates. Change should be a good thing, where people develop andgrow, but we live in a world where people are expected to have all the answersand not having the right answers is seen as a sign of weakness.

We come from a tradition where the more we learn, themore we explore, the more we realize what we don't know. And the more we realize what we don'tknow the more we become committed to investigation, to inquiry, to sitting atthe heel and learning at the elbows of people who know what we don't know. That is what we try to do with thebook. We offer a lot of knowledgebut also talk about our shortcomings, what we struggle with, personally andideologically. Even as we go overissues of race versus class, talk about the contours and contradictions ofmasculinity, or the sources of the prison industry, we are struggling with thisstuff, with each other and ourselves. We want people to know that is OK. You can't be a committed cultural worker, an active engaged intellectualif you constantly don't wrestle with yourself, constantly don't struggle todevelop a sharper and more coherent vision of the world.

DJL: When I originally heard about the book, myassumption was the it was going to be primarily about incarceration and the criminaljustice system. I thought it wouldbe an anchor and a central theme in the book, and while incarceration is atheme (and a chapter in the book), it does not dominate the book. Did you both make a conscious decisionnot to limit your conversations to that place?

MLH: It was and wasn't. At one level, we just let the conversations go where theytook us. Mumia had just finished Jailhouse Lawyers and he hasobviously written Live from Death Row . He has really engaged the prisonquestion in great depth. I alsohave written and lectured on that topic. We are both excited by that conversation and focus a great deal of ourenergies on criminal injustice and prison industry. But we also wanted to expand the conversation; we did notwant to reduce our intellectual scope and interest to that thing.

It was unconscious in that we just explored the topicwe are about. It was consciousbecause we called the book The Classroomand The Cell but did not reduce it to prisons and schools,our areas or expertise. We calledit The Classroom and The Cell becausein many ways those two locations speak to the condition and possibility ofblack folk, along with our respective positionalities. As we do the book, hesits on death row, although recently move to slow death row. And I am in an Ivy League school. To that extent, the classroom and thecell was about us, our condition, rather than the scope of the book.

DJL: One of the most profound aspects of the book restswith its ability to challenge what Angela Davis has described as prisons'ability to magically make people disappear.

MLH: We are grateful for that opportunity to challengethat belief. Prisons, likeslavery, are instruments of social death in so many ways. Yet, people are stillfighting and struggling. When wehave people like Mumia Abu Jamal screaming from the wilderness, it is areminder that people who are locked up inside the dungeons of America's prisons,are still alive, still kicking and have so much to offer. It is so easy to think about the peoplelocked in these dungeons not as human beings. It is easy to lose sight of that humanity. It is easy once we put that label ofcriminal on them to see them as a class, as an element of people who don'tdeserve our support, our love, and our investment. Mumia reminds us that these are people and these are peoplewith possibilities. If we listento Mumia's voice, if we cared what he was saying, if we read the prisonwritings of so many brothers and sisters who have been incarcerated, manyunjustly, we would have a whole different posture on prisons, on vulnerablepeople.

DLJ: This comes through the book as society systemicallyimagines those incarcerated as living in another world, yet the book revealsthe dialectics and engagement between those who are "free" and incarcerated peoples.

MLH: A day doesn't go by where I don't get a letter fromincarcerated brothers and sisters. What would be shocking to many is how much they are engaged with theworld, how much they are unpacking the complexities of the world, how much theyare reaching out folks, advocating for themselves, and bringing seriouscritique to bear. They are soalive and kicking. It is easier tohide that fact; it is easier to pretend that they are just sitting in a cagesomewhere.

DJL: We see this through the dehumanization ofincarcerated people, through the efforts to represent those locked up as "animals,"all in an effort to sanction, rationalize, and justify such an inhumanesystem. Your conversationshighlight the agency, the love, the families involved, the beautiful insightsand the humanity, which collectively disrupts the dominant narrative and theefforts to erase people from our consciousness.

MLH: Yeah, brother, that is was our goal.

DJL: You end each chapter with a list of books forfurther reading. Talk about that

MLH: Karla Holloway in her great book, Bookmarks: Reading in Black and Whites ,talks about the tradition of black writers leaving their bookmarks, who theyhave read, who they were reflective of what they were engaging. It was also about affirming thehumanity of black folks, the intellectual capacity of black folks by showingthat literacy, so often seen as the seat of reason and signpost of humanity,was something that we had. We arenot so committed to proving that we are literate but following in thattradition. We also wanted to leavea map of what we have read, what informs us; these are books that shapedus. I can't think aboutmasculinity without thinking about [Mark Anthony Neal's] New Black Man. I can't think about love without thinkingabout bellhooks. MichelleAlexander shapes my understanding of the prison crisis. We want people to know where we camefrom. In a practical sense, wehope that people would keep going with the conversation, and listing the bookswill hopefully help in that process. Just last week, I got a letter from a brother in prison who requestedJames Baldwin's Fire Next Time because it was on thelist. They wanted to go deeper onthis love thing

DJL: Ithighlights the ways that the conversations reflect on the past while imagininga future. Was there anything from your conversation that surprised you or leftan indelible mark? MLH: There are so many moments. It is easy to think about radicalfigures and political prisoners as very serious, as revolutionary actionfigures. Going more deeply withMumia, and I realized his full humanity – I had lost sight of that aswell. He is one of the mostplayful and funny people you could ever meet. He is hilarious. He is one of the most loving, caring and gentle people you would evermeet, something you would never know from the public representations ofhim. He really represents a complexmasculinity. All of that comesthrough our conversations. He is so strong. He hasbeen on death row for a crime he didn't commit – he is an enemy of the state –yet he is so strong. You can losesight that he hurts sometimes, that he endures pain like everyone else. He is away from his family, his life;he has been animalized for 30 years. As we are fighting for those incarcerated, as we are advocating forpolitical prisoners, we must remember that they are full-people, with a rangeof emotions and we have to keep track of all of them.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of CriticalCulture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. Hehas written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing inboth popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy ofpopular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, andpopular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis.He is the author of Screens Fade toBlack: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Marc Lamont Hill is Associate Professor of Education at the Teachers College of ColumbiaUniversity. Hill is co-author, with celebrated political prisoner, Mumia Abu Jamal, of the new book The Classroom and the Cell: Conversations ofBlack Life in America . Heis also the author of Beats, Rhymes, and Classroom Life: Hip-Hop Pedagogyand the Politics of Identity and host of Black Enterprise's Our Voices.

Published on February 16, 2012 10:55

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.