In defense of Brainstorming: against Lehrer's New Yorker article

Jonah Lehrer's recent article in the New Yorker Groupthink: the brainstorming myth, is a tragedy. It makes many poor conclusions and will do more harm than good.

The article is an attack on the concept of brainstorming, but his assumptions and reasoning are flawed.

I have no stake in brainstorming as a formalized thing. It's a method, and I've studied many idea generation methods. If done properly, in the right conditions, some of the them help. I'm not bothered by valid critiques of any of them. However, sweeping claims based on bad logic and careless thinking need to be addressed.

Here are 4 key things he doesn't mention, which shatter his conclusion:

Nothing matters if the room is filled with morons or strangers (or both). If you fill a room with stupid people who do not know each other, no method can help you. The method you pick is not as important as the quality of people in the room. The most important step in a brainstorming session is picking who will participate (based on intelligence, group chemistry, diversity, etc ). No method can instantly make morons smart, the dull creative, or acquaintances intimate. The people in Nemeth's research study, the one heavily referenced by Lehrer, had never met each other before and were chosen at random. A very different environment than any workplace.

Brainstorming is designed for idea volume, not depth or quality. Osborn's (the inventor of brainstorming) intention was to help groups create a long list of ideas in a short amount of time. The assumption was that later a smaller group would review, critique, debate, later on. He believed most work cultures are repressive, not open to ideas, and the primary thing needed was a safe zone, where the culture could be different. He believed if the session was lead well, a positive and supportive attitude helped make a larger list of ideas. Obsorn believed critique and criticism were critical, but there should be a (limited) period of time where critique is postponed. Other methods may generate more ideas than brainstorming, but that doesn't mean brainstorming fails at its goals.

The person leading an idea generation session matters. Using a technique is only as good as the person leading it. In Nemeth's research study, cited in Lehrer's article, there was no leader. Undergraduates were given a short list of instructions: that was the entirety of their training. Doing a "brainstorm" run by an idiot, or a smart person who has no skill at it, will disappoint. This is not a scientific evaluation of a method. Its like saying "brain surgery is a sham, it doesn't work", based not on using trained surgeons, but instead undergraduates who were placed behind the operating table for the first time.

Generating ideas is a small part of the process. The hard part in creative work isn't idea generation. It's making the hundreds of decisions needed to bring an idea to fruition as a product or thing. Brainstorming is an idea generation technique, and nothing more. No project ends when a brainstorming session ends, it's just beginning. Lehrer assumes better idea generation guarantees better output of breakthrough ideas, but this is far from true. Many organizations have dozens of great ideas, but fail to bring those ideas into active projects, or to bring those active projects successfully into the market.

1. Understanding Idea Divergence vs. Convergence

Lehrer writes:

"While the instruction 'Do not criticze; is often cited as the important instruction in brainstorming, this appears to be a counterproductive strategy. Our findings show that debate and criticism do not inhibit ideas but, rather, stimulate them relative to every other condition."

The intention of brainstorming is not to eliminate critique, but simply to postpone it. Workplaces are notorious for killing ideas quickly with phrases like "We tried that already" or "that won't work here" or even "that's too crazy" (List of familiar idea killers heard regularly in workplaces). Great ideas often seem crazy or weird at first and if they are discarded or criticized before given time to breathe they're lost before they had a chance to show their merit.

In ordinary life when people face big decisions, like where to go on vacation, it's common to come up with a big list of ideas, only adding items for a time. And then once the list seems reasonably long, only then does critique and debate start. This is known as divergence / convergence. You explore and add (diverge) and then cull and refine (converge). Most creative people, and processes, shift back and forth between divergence (seeking, exploring, experimenting) and converging (eliminating choices, simplifying, deciding). Brainstorming and nearly all idea generation techniques are divergence acts. And need to be paired with a separate activity that converges.

Simply put, there is an assumption in most research about creativity that only a singular method is ever used. This is wrong. Most successful creative teams use a combination of methods. Sometimes people work alone, sometimes in groups. Sometimes there is a formal activity, sometimes not. Sometimes the goal is to diverge, sometimes the goal is to converge. Their effectiveness is the combination of all of these activities over the course of a project. But most research assumes there is only one event for creativity that ever happens, and seeks to find the ideal event, which is absurd. I understand the focus on a single activity simplifies research, but it also limits the application of that research.

In Osborn's best book on the brainstorming method, Applied Imagination, he wrote on page 197:

"Although creative imagination is essential… judgement must play an even larger part."

And he details several processes for evaluating, critiquing, and reporting on ideas. On page 200 he states:

"A list of tentative ideas [e.g. the output of a brainstorming session] should be considered solely as a springboard for future action… as a pool of ideas to be screened, evaluated and further developed before solutions can be arrived at."

2. Reading the 2003 Brainstorming Study

The primary thrust of Lehrer's critique is based on a 2003 study by Nemeth (PDF), where students were divided into groups and given 3 different sets of instructions. In one group, no instruction was given ('Minimal'). In the second group, basic brainstorming rules were given ('Brainstorming'). In the last, brainstorming rules were given, plus students were allowed to critique each others ideas ('Debate'). But no group was trained in how to brainstorm, nor given an example of effective brainstorming to watch.

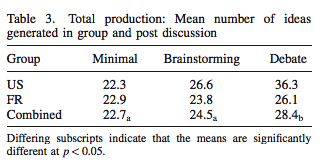

Is the debate group brainstorming, or not? They were given the same instructions, plus one additional one ('it's ok to criticize'). The results do show that the group that could critique generated more ideas: but not many more. For all the participants, it was a difference of ~4 ideas. 28.4 ideas for the "debate" group and 24.5 for the "brainstorming" group. About 14%. In the U.S. this number was much higher, closer to 30%.

But these columns are mislabeled. The debate groups was given brainstorming instructions, as well as an instruction to debate. It should be labeled "Brainstorming with debate". If the only instruction they were given was to debate, it'd be a fair comparison. But it isn't.

3. Is Brainstorming Useless?

Lehrer's writes:

"But if brainstorming is useless, the question still remains: What's the best template for group creativity?"

He's wrong. The data from Nemeth claims brainstorming (Column 2 in the table above) is more effective than giving people no advice at all, but not as effective as brainstorming where criticizing is allowed. I don't agree with Nemeth's conclusions, but Lehrer does, and assuming he'd read the study he'd have seen the table above which show brainstorming generated more ideas than the control group.

More importantly, he's asking the wrong question. There is no singular best template for group creativity. When I'm hired to advise teams, the first thing I do is study the culture of the team. My advice will be based on who they are and what will work for them, not on an abstract set of principles. Just as there isn't a best template for group morale, or teamwork, or group anything. Is there a singular best template for good writing? For being a good person? A singular template denies how divergent individuals, teams and cultures are. Nemeth's data shows a wide disparity between French and American success at brainstorming: clearly culture does matter.

Lehrer assumes there is a universal principle that, if discovered, would make everyone more creative. This works against the very idea of creativity: which is that each person sees the world in a different way, and it's through exploring those differences, rather than avoiding them, than new and different ideas can be found. For groups, this means each group has it's own strengths and weaknesses, and what will help or hurt their creative output will differ. Some teams are too freewheeling, others not enough.

4. Anecdotes, Data and MIT's mythical building 20

Lehrer goes on to discuss The legendary building 20 at MIT's Cambridge campus. He writes:

"Building 20 and brainstorming came into being at almost exactly the same time. In the sixty years since then, if the studies are right, brainstorming has achieved nothing – or, at least, less than would have been achieved by six decades worth of brainstormers working quietly on their own. Building 20 though, ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time, a space with an almost uncanny ability to extract the best from people. Among M.I.T. people, it was referred to as the magical incubator."

MIT is one of the greatest concentrations of brilliant people in the history of the world. The campus is filled with buildings where great things were invented. Lehrer offers no data about the number of inventions discovered in Building 20 vs. Building 19 or E15 (where the famed Media Lab resides). He mentions Building 20 "ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time", but there is no actual ranking. If you wanted to measure the magic of building 20 scientifically, you'd perhaps replicate the building in the middle of an empty field in Kansas, and fill it with average people. Does magic happen? More magic than other kinds of buildings in the same place? Nehmer's brainstorming studies were done with random college undergraduates who had just met. If you want to compare brainstorming to Building 20, you'd need to try to place some fair comparisons, which Lehrer does not do.

I agree environment matters, but there's plenty of evidence great things happen independent of environment. There was nothing magical about the buildings used for the Manhattan project. Nor for the NASA engineers who worked on the Apollo 11 moon landing mission. The car garage is the prototypical silicon valley environment for innovation, and many ideas that drive our tech-sector came from garages and cubicles. How does the legend of Building 20 compare with these other buildings? What shared lessons can be learned that incorporates these diverse examples of environment? Lehrer doesn't say. In building 20, what idea generation techniques did they use (and was brainstorming one of them?), or did they all just meet randomly in corridors? He also doesn't say. Did they work together at blackboards? At the cafe? I'm sure they used many different methods, and the combination of those methods matters.

5. The only lessons I can derive

The best lesson I can pull from Lehrer's mess of an article is this: creativity is personal. Building 20 was built cheaply and seen as a failure, which made it easier for motivated creatives to rearrange and redesign the environment. There were fewer rules than your typical building. They were allowed to take control over how they worked. The diversity of people forced people to hear different points of view. And the highly empowered and competitive pool of makers ensured things would ship, and not languish in bureaucracy or self-doubt.

If you want more creativity, hire people who demonstrate creativity. Do not expect to magically graft it onto people you hired for their rigid conservatism. Then give them resources and get out of their way. Let them decide what methods to use or not. If you want to know how to generate ideas in groups, go find a creative group and watch what they do. You'll learn more from observing that experience than Lehrer's article.

Related: A previous defense of Brainstorming against Marc Andresen, with supporting links.

Related posts:

In defense of brainstorming

Microsoft no more

#34 – How to run a brainstorming meeting

Do headlines make us dumber?

Last stop: Adobe