Memoir and the Dangers of Nostalgia

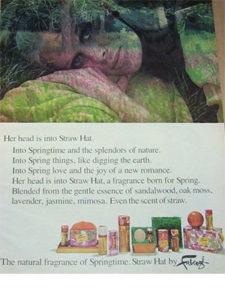

It’s 1974, and I’m eighteen years old. I drive a slant-six Plymouth Duster, and I wear my hair long and my jeans tight. I hang out at John Piper’s pool hall, where I play the pinball machines. When the weather’s good, I play basketball on the schoolyard. My game has never been better. I’m young and strong and a little cocky. I like to cruise the streets of my small town just to see who I can see and, of course, to let them see me. I have a girlfriend named Cathy, and I have that head-over-heels, pie-in-the-sky, catch-me-I’m-falling-in-love feeling about her. I have no way of knowing that thirty-eight years later I’ll marry her. At the time, I only know the scent of her Straw Hat perfume, a scent she claims now she doesn’t recall ever wearing, but I stand by my memory. I remember that perfume, and how it felt to hold her in my arms, and the sway of her hips, and the way she whistled her “s’s” when she called me, “Sweets.” These are the days of my glorious youth, days that now can seem so distant but at the same time can seem so near.

It’s 1974, and I’m eighteen years old. I drive a slant-six Plymouth Duster, and I wear my hair long and my jeans tight. I hang out at John Piper’s pool hall, where I play the pinball machines. When the weather’s good, I play basketball on the schoolyard. My game has never been better. I’m young and strong and a little cocky. I like to cruise the streets of my small town just to see who I can see and, of course, to let them see me. I have a girlfriend named Cathy, and I have that head-over-heels, pie-in-the-sky, catch-me-I’m-falling-in-love feeling about her. I have no way of knowing that thirty-eight years later I’ll marry her. At the time, I only know the scent of her Straw Hat perfume, a scent she claims now she doesn’t recall ever wearing, but I stand by my memory. I remember that perfume, and how it felt to hold her in my arms, and the sway of her hips, and the way she whistled her “s’s” when she called me, “Sweets.” These are the days of my glorious youth, days that now can seem so distant but at the same time can seem so near.

I’m recalling those days now because I want to say something about what it takes to look clearly at the various versions of ourselves when we write memoir. We have to look beneath the nostalgic recollection of our younger days in order to see the layers of truth that nostalgia tries to hide. We have to see the details that we tried our best to conceal when we were living those younger days.

The truth is my Plymouth Duster had a 198-cubic-inch, 125-horsepower engine that was built for economy and not speed. It’s true I wore my hair long and my jeans tight, but my hair was often a mess of thick waves that Cathy once tried to tame with a Ronco Trimcomb that my family owned. It was so dull and pulled so badly, I was nearly in tears by the time she was done. The sneakers I wore when I played ball often had holes in the bottoms, and I don’t know why I didn’t buy a new pair. The grain on the ball we used was so slick it was hard to shoot with any accuracy. I wasted so much money in that pool hall because I didn’t want to go home. I needed a place to be. The only thing completely true in the opening paragraph of this post is the way I felt about Cathy—that and the Straw Hat perfume, which I’ll continue to insist is accurate.

I stand by what I felt about Cathy—and continue to feel to this day—but to write truly about that time period, I’d also have to write about how out of place I felt when I first started attending the nearby community college—how I’d often sit in my car when I didn’t have a class, writing poems and feeling insecure. I’d also have to write about what it was like to be the only child of older parents—my mother was sixty-four in 1974, and my father was 61—and the fear I had that they would die while I was still young. My father and I had finally reconciled after a difficult childhood and early teen years, but I carried with me the memory of his belt against my skin and the ugliness of our words. I’d have to write about how desperate I was to find someone who would treat me with tenderness, and how that fact made me especially susceptible to falling in love.

We can’t romanticize ourselves or our pasts when we write memoir. We have to be honest. We have to come clean. We have to see the truths of our lives that lurked beneath the images we tried to present to the larger world. We have to be willing to put the details on the page that reveal the inner lives we lived. The contrast between the way we’d like to remember our younger selves and the truths we have to confront can make for powerful writing. We can’t let nostalgia seduce us. There’s always something more truthful on the other side of it.

The post Memoir and the Dangers of Nostalgia appeared first on Lee Martin.