Servold, Bachelard, and Three Unnamed Children

Perfection is the thirteen-second clip that comes about three minutes into a film you could easily forget was released in 2020, Emerica’s Green. The skater is Dakota Servold dressed in all black but for his belt. He does three tricks on a narrow and pretty obviously non-American sidewalk through one of those small shared outdoor spaces that European apartment buildings are so good at. It’s an Oz-like yellow pathway of small squares that rattle under Servold’s and the filmer’s wheels and there’s an incline, the path drops and flattens as it leads through the grass and toward a set of stairs. The lawn is a deep, verdant green with trees in planters on one side and shrubs lining the building on the other. Fallen yellow leaves dot the yard.

He lands a fakie three-sixty-flip and swerves twice along the narrow path’s grade before regaining control just as it levels out. Momentum carries him through the path’s crook and he sets up for a clean and high-speed half-cab flip. Then he pushes twice, moving now very fast indeed, and crouches, digs in his back foot, and pops a back lip down a handrail made of narrow piping. As the camera brakes at the stairway’s top, Servold lands on top of some kind of manhole, and the shot cuts just as he’s about to collide with the bike rack against another apartment building.

But look at the three German children running alongside the path! Two have long blonde hair, one is in a dress, and the third, a boy, leads the pack. There’s an ongoingness to their running at the clip’s start, and soon the one in the blue dress falls out of the shot, and then the second one, with the ponytail, and meanwhile the third boy is fastest, barely keeping up as Servold powers toward the rail, but he fades too, leaving only Servold, the stairs, the back lip.

The more that I watch this clip, the more it feels to me like a small miracle of framing and motion. Only once at the very outset does any of Servold’s body leave the frame—some of his right arm on the fakie-three—and yet we never feel a distance. We could touch him if we wanted, just by reaching, except somehow these children are in the frame too, the lawn and whatever game they believe they’re playing. It’s an open shot, and inviting, but close enough to see the wear on Servold’s right shoe. There is nothing that quite wears-in like an Emerica, after all, and in fact the entirety of Green functions as a kind of reminder to the shoe-buying world that it’s not over yet, or not quite, for skater-owned shoe companies.

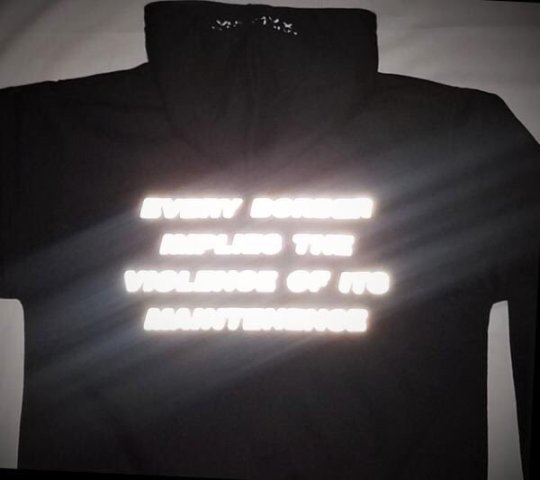

“Every border,” wrote Ayesha Siddiqi, “implies the violence of its maintenance.” It is true that the upkeep of skateboarding’s borders has demanded the kind of exclusionary harm that we’ve learned to diagnose (and in some cases, treat) as gatekeeping. It is also meanwhile 100% true that there is something one feels while watching Green that one doesn’t while watching, say, a RedBull skate video, or many of the edits that come tumbling out of the big footwear tubes. Though it’s also become harder and harder to talk about this stuff, largely because the blurred and confounding status of skateboarding’s once fairly defined borders.

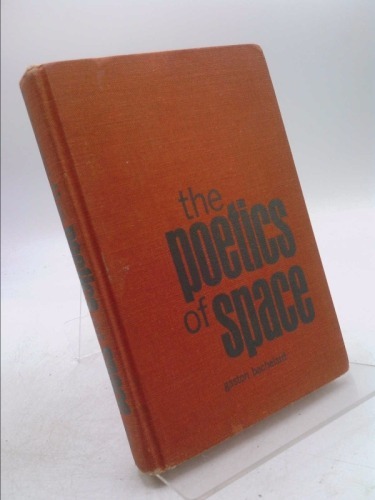

In a late chapter of The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard confronts the “profound metaphysics” of the outside / inside dialectic, the language of which is everywhere we look, each use of which “confers spatiality upon thought.” Over the years, as skaters have spoken in terms of “core” or “endemic culture,” we have abided by what Bachelard, quoting Jean Hyppolite, calls, “a first myth of outside and inside.” Can any of us belong to anything without defining that belonging by such a spatial metaphor? It is difficult. And it is a challenge faced by any community that is set off somehow from a broader population, any tribe or nation, any single self facing any single other. One wants belonging to have meaning, after all—meaning is the reward that belonging confides.

Our skate borders, by now, have been as gerrymandered as any in the US. The original “SB” in Nike SB was a message to skate retail outlets and their niche consumers—a gesture to distinguish between us and general athletes, a nod to both the specific needs of skaters and our specific commitment to style. It felt, back then, a little like respect. Over time, this respect was enough for Nike SB to leap from the confines of the skateshop into the broader marketplace. Along the way, “SB” morphed from request to claim, a credentialed bit of rhetoric in an argument that has, by now, achieved something like meaninglessness —what does it mean for Travis Scott and the Grateful Dead to have their names attached to an “SB” shoe? Truly: who fucking cares. In any case, “SB” means less to those of us who identify as “skaters,” surely, than whatever it means to those who don’t.

Did you read, earlier this year, Ariana Gil’s article, “The Best Don’t Get Caught: The Case of Supreme,” in Cultured Magazine? By now Supreme’s been sold again, the topic is exhausting, but Gil’s treatment of “one of the most mythical brands of all time” diagnoses with icy precision some hard truths about our little word. Gil turns to a framework proposed by new media scholar McKenzie Wark that treats branding as a third, complicating entry into the historic model of two dominant economic classes, capitalists and workers. A brand, so it goes, achieves its unified commodity value through the production of information vectors based on narrative and image data. Gil paints Supreme’s brand vector since its founding in 1994 as a balance of cool exclusion and delinquency, a pastiche that draws from homelessness, unemployment, and other unproductive activities, “from kicking wood to smoking dope to graffiti,” all of which become productive to Supreme’s own valuation. As a result, “what was once an ‘insiders’ club of self-identified ‘outsiders’” became, quite suddenly in 2017, a billion-dollar company when half of it was purchased by The Carlyle Group, the largest private equity group in the world.

Back to skateboarding, how about? Maybe, like me, you are equal parts intrigued and enraged by the current incarnation of Bill Strobeck. In 2015 I wrote that Ty Evans films skateboards, Greg Hunt films skate spots, and Strobeck films skateboarders, brutalizing the zoom function of a new generation of HD cameras to insist upon us a series of fingernails, blemishes, and other details of embodiment. By Candyland, that body interest reached a new level, and came at the cost of spots and tricks and also, regarding women and non-binary/genderqueer people on the street, basic human respect.

And so, a valuable exercise in forcing the question of just what exactly it is we’re watching when we watch a skate video: body, board, spot, contextual noise that surrounds spot, and so on. Bill’s gaze has a long history of being real good with skateboarders in motion but sometimes creepy and maybe sexist and definitely adolescent. And to my eyes, it’s never felt more like a prison than in Candyland. Which is a thing worth recalling—the myriad gazes so central to our consumption of skateboard media, the many thousand cameras in our pockets, are extensions of the tastes and values and aesthetics of whoever holds them. It is the obvious reason why a film of girls and women and nonbinary skaters shot by Shari White feels different—Shari’s camera does not leer—a point obvious but no less important for its obviousness.

Which all makes a clip like Dakota Servold’s three-trick line among socialized housing somewhere in Germany feel like a revelation. Green opens with a shot of Emerica shoes—a minor secret about Emericas at this point: the model does not matter; whatever the specifics of toe box and side paneling, they are all the same model and it is “the Emerica”—landing on the blacktop inside of a just-hopped Californian fence. And by virtue of necessary budget limitations and/or brand ethos, Green is a California video to the core, built of red curbs and palm trees and schoolyard blacktops. Having lost the twenty-year face of their brand, post-Reynolds Emerica exhibits no anxiety or insecurity, no desire to venture laterally or cater to anyone beyond their established demographic. And yet somehow, despite most of them being white dudes cut from the same motorcycling and flanneled and long-haired cloth, Green’s two song’s-worth of montage without name titles results in no confusion—you can mostly tell who they are! Jon Dickson continues his interpolation of a heftier, dockhand or mechanic version of Dylan Rieder, and it is both a powerful ode and powerful in itself, a reckless and gruff Dylan echo, stunning to behold.

And tucked amongst all of this denim and flannel and leather and hair, all the wearing and the tearing, we’ve got three German children running to keep up in the far right of a widescreen, high-definition frame. What a thing to be able to watch immediately on the heels of noticing Servold’s worn-out shoe. What a richness.

It brings me to that way of seeing we call “naturalism,” and turning once again to Annie Dillard, who wrote as well as anyone about the natural world. “I would like to know grasses and sedges—and care,” she tells us. Elsewhere, she has “just learned to see praying mantis egg cases. Suddenly I see them everywhere.” This is not a matter of theory or even comprehension, in fact what Dillard celebrates in her nature writing often has little to do with “meaning” at all. Dillard’s project is about metaphor as a tool to describe what is seen and what resists language. It is the enrichening of her lived experience that can only come of her learned competence. Of not just knowing but also caring, and from these two experiences becoming even more engaged. And so the cycle spins with each new level of engagement reverberating back into the body where knowledge and care live, an increasing richness of living.

People who have skateboarded long enough know that skateboarding, too, works this way. Seeing and caring work in tandem and echo. To care more about skateboard media is to change the way the body goes out and does it.

The filming of Emerica’s Green is not artful exactly but artfully proficient. In Tim Cisolino’s hands, the camera moves but does not jerk. The skaters and spots are framed deliberately. In Germany, following behind Dakota Servold, that means a wide-angle shot that holds space for the children to run alongside and play through the grass. It is a brief sequence, thirteen seconds out of a nineteen-minute film, that presents of speed and sound and several human bodies moving through the world. Of shoes that have been worn long enough to show wear. Under pressure as the last defense against Nike and Adidas and New Balance, Emerica’s choice was to turn to the viewer and encourage each of us to see what we could. Emerica know what we expect of them, and we know they know that we know, and so on. Were it any other relationship, we would call this intimacy.

A Christmas treat for you to read.