A New Kind of Vaccine for COVID-19

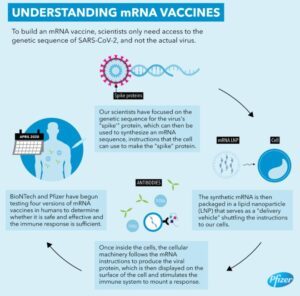

Pfizer’s description of how an mRNA vaccine works (click for larger version)There has been a lot of talk about Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and a reader asked me to comment on it. The company claims it is more than 90% effective at preventing the disease, which is better than what most health-care experts were expecting. If true, that news is exciting enough. To add to the excitement, it is a new kind of vaccine that has great potential, if it works the way it is supposed to. There is another company trying to produce a similar vaccine, but it looks like Pfizer is in the lead, so for the purpose of this article, I will focus on its version.

Pfizer’s description of how an mRNA vaccine works (click for larger version)There has been a lot of talk about Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and a reader asked me to comment on it. The company claims it is more than 90% effective at preventing the disease, which is better than what most health-care experts were expecting. If true, that news is exciting enough. To add to the excitement, it is a new kind of vaccine that has great potential, if it works the way it is supposed to. There is another company trying to produce a similar vaccine, but it looks like Pfizer is in the lead, so for the purpose of this article, I will focus on its version.

Let me start by saying that I have no connection to Pfizer or any other pharmaceutical company. I am a science educator who writes about science issues like this one. I am also not a medical doctor or medical researcher. I am simply a nuclear chemist who has broadened my knowledge base by writing (or co-writing) a series of textbooks used by home educators and teachers in Christian schools. Thus, I am no expert on these matters. However, I get most of my information by reading the scientific literature, which allows me to avoid a lot of the misinformation found in the standard media outlets and (even worse) social media.

Before I talk about Pfizer’s vaccine in particular, I want to explain how this kind of vaccine works. To understand that, remember that a traditional vaccine uses a weakened/inactivated form of the pathogen whose infection it wants to prevent (or a chemical mimic of that pathogen). This causes your body to react as if it is being infected by the real thing. As a result, it mounts a defense that is specific to that pathogen and remembers how to fight it. That way, if you get infected by the real thing, it can mount a swift immune response. This process takes advantage of your acquired immune system. However, you also have an innate immune system, and the active ingredient of the vaccine does not stimulate it. As a result, traditional vaccines have additives, called adjuvants, which are designed to stimulate your innate immune system. That way, everything in your immune system works the way it is designed to work.

This new kind of vaccine takes a different approach. Rather than injecting you with a weakened/inactive version of the pathogen (or a chemical mimic), it injects you with the instructions that your cells need in order to make a protein that is found on the pathogen. These instructions are coded in a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA), which is the way a cell expects to receive such instructions. Some of the cells in your body will make the protein according to those instructions and “display” it, which will cause your immune system to think it is being attacked by a pathogen. This will stimulate your acquired immune system to respond. It will then remember that response so if you get attacked by the real thing, it is ready.

You can’t just inject mRNA into the bloodstream, however, as it will be removed rather quickly. Thus, the mRNA is enclosed in a fatty membrane called a “lipid nanoparticle.” The membrane and its mRNA can enter your body’s cells. Once that happens, cells recognize the mRNA as instructions for making a protein, and it is sent to a protein-making center called a “ribosome.” Interestingly enough, the membrane-enclosed RNA also stimulates the innate immune system, so this kind of vaccine needs no adjuvants, at least based on what has been seen so far.

But what happens after the mRNA is used at the ribosome? After a while, it decays away and is recycled by the cell. Why? The DNA in the nucleus of each cell contains instructions for making the proteins that the cell needs to make, but it never leaves the nucleus. As a result, the instructions are sent from the nucleus in the form of mRNA. Thus, there is a lot of mRNA in the cell, and all used mRNA decays and is recycled as a matter of course. This kind of vaccine just adds one more mRNA to the cell, and the cell treats it like it treats any other mRNA.

But wait a minute. If mRNA comes from DNA, is it possible that this mRNA can somehow interact with your DNA, fundamentally changing it? Not based on what we know about the cell. DNA is found in the cell’s nucleus, and mRNA cannot enter the nucleus; it can only leave the nucleus. Thus, there is no way this mRNA can affect your DNA. There is a class of viruses called “RNA retroviruses” that have the ability to take their RNA and convert it into DNA, which can then enter the nucleus. However, that virus has a special chemical (a reverse transcriptase enzyme) and other support chemicals to get that job done. With this kind of vaccine, there aren’t any chemicals like that, so as far as we know, there is no way for this mRNA to even come close to the cell’s DNA.

Why would you want a vaccine like this? Because it has several advantages over a traditional vaccine. First, there are no adjuvants. Every time you add another chemical to anything that goes in the body, you have increased the possibility of side effects. Fewer chemicals should mean fewer possible side effects. Second, since this is fully synthetic, it is relatively fast to produce. Thus, it is thought that this kind of virus can be made for situations just like this one, where the sudden introduction of a pathogen produces a new disease that is infectious. Third, the development of the vaccine doesn’t require the virus itself. All you need is the sequenced genome. Thus, there no chance of a virus-related accident during production.

Regarding Pfizer’s version of this vaccine, not much is known. The early clinical trial has been published, and its results are very encouraging. Only 45 volunteers were involved. 36 got the vaccine, and 9 got a placebo. Those who got the vaccine produced more antibodies than what is seen in patients who have recovered from COVID-19, indicating that the vaccine produces a more than adequate immune response. Almost all of the volunteers who got the vaccine reported pain at the injection site, and many reported headache, fatigue, and fever, which were dependent on the dose that was given. Only 2 of the 9 placebo-injected people reported such side effects. There were no severe side effects for anyone. A later clinical trial involved 195 participants and two versions of the vaccine. One version produced fewer side effects than the other, but the immune responses in the participants were similar to those in the first trial. Once again, then, very encouraging results.

Of course, both clinical trials had small test groups, which is why the current clinical trial (for the version that produced fewer side effects in the second trial) has 43,538 participants. Unfortunately, the data related to that trial are not available, since it is not over yet. However, based on the information I linked previously, that trial has reached a milestone: 94 patients have tested positive. This is important, because 94 infections among the participants is statistically significant enough to conclude whether or not the vaccine is protective against the virus. Based on what the company is saying, more than 90% of those cases must have been in the group that received the placebo, which means the vaccine provides strong protection against the disease. However, we don’t know that yet, since the data have not been released.

Nevertheless, Pfizer cannot get emergency authorization for this vaccine until the trial has been going for two months, because the side effects must be tracked for at least that long. Supposedly, that milestone will be reached by the third week of this month. The clinical study will continue until at least 164 of the participants have been infected so that a better estimate of the vaccine’s effectiveness can be determined. I am personally very excited about this vaccine (and other candidates like it), but until more data are published, I will withhold judgement. However, if the data from the current clinical trial are as good as the data from the early one, I will be eager to get an injection.

I will add one note of caution. This kind of vaccine has never been used before, except in clinical trials. Thus, nothing is known about its long-term effects, except what is predicted based on our current knowledge of cellular processes. Those who are more cautious about medical interventions should take that into account. Of course, I must also add that we don’t know what the long-term effects of COVID-19 infections are either, so one must weigh both unknowns when making any decision related to the disease.

I will keep my readers apprised of any new developments.

The post A New Kind of Vaccine for COVID-19 appeared first on Proslogion.

Jay L. Wile's Blog

- Jay L. Wile's profile

- 31 followers