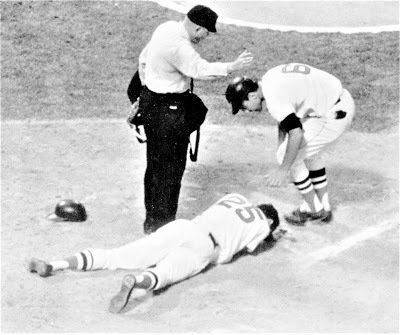

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967: Tony Conigliaro struck by pitch.

Mark Gray, the protagonist of "Blue Hill," is a young Red Sox fan when slugger Tony Conigliaro is beaned by a pitch during the Sox "Dream Team" of 1967. The pitch changed the real-life Tony C. -- and had a profound impact on the fictional protagonist of my new novel.

To learn more about the book, which published on October 6 - and to order in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

I close my eyes and I can see the sun setting over Fenway,can feel my hand inside my glove, a Wilson that Mom gave me for my ninth birthday. I hear Dad, happy for the first time since Mom took sick, explaining with uncharacteristic enthusiasm why the bleachers are the statistically proven best place to catch a Tony Conigliaro home run because of how he pulls the ball—nothing, of course, about how the bleachers are all we can afford. I didn’t come to that realization until much later.

“Today’s the day, Mark,” he said, “I feel it.”

I said: “Does He feel it, too?”

And Dad saying impishly: “Who—the Big Guy?”

This was Dad at his wickedest—you knew he’d be good for an extra Coke, a day like this.

“Yeah, the Big Guy,” I said.

“Oh, yes, He feels it, too,” Dad said. “I can tell, because we’ve been doing a lot of talking lately.”

Talk was what Dad called prayer, when explaining it to little kids.

Even if you’re only marginally into baseball, you know where this one goes.

Jack Hamilton was pitching for the California Angels when Tony C. came to bat. I had Dad’s binoculars and I followed Conigliaro as he left the warmup circle. The first ball was a strike. Conigliaro fouled the second off behind first base. The next pitch, a fast ball, caught Conigliaro in the left cheekbone. I heard it—I swear I did, three hundred and seventy-nine feet away—a sound like a hammer on wood.

Tony C. fell.

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967.

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967.The crowd went silent, and Fenway Park suddenly seemed frighteningly huge, and then the woman next to me began to cry.

She was a woman like Lisa: pretty, ponytailed, dressed in cut-offs and a tee shirt with Tony C.’s number. I remember having stared at her breasts when she wasn’t looking—how I saw Dad sneaking a look, too. I remember her telling me how she went every weekend to the club where Tony C. hung out. I remember the smell of the baby oil she rubbed onto her arms and legs, tanned to bronze, like Bridget Bardot, whose picture I’d secretly cut from a Look magazine from the library. I was a boy, discovering, awkwardly like all of us, sexuality.

I remembered all that and could not but wonder, sitting there at Fenway now with my own son more than thirty years later, where she was now and did she still feel good enough about herself to tan or did she heed the emerging warnings about skin cancer, and was she a grandmother—and did she have even the faintest memory of the boy sitting next to her that day.

I didn’t cry, at first.

I knew that any second, Tony C. would get up, brush himself off and take first base, and the next time he faced Hamilton, he would send his darn beanball all the way to Kenmore Square. Yaz would knock one out, too, and maybe George Scott also for good measure, and that would teach the Angels a thing or two about messing with the man.

But Tony C. didn’t get up.

He lay in the dirt, motionless, as men in white rushed out with a stretcher.

I started to cry then. Dad talked soothingly and held my hand, and when I didn’t stop, he led me out to Landsdowne Street. I didn’t know, of course, that he’d already decided I would never play baseball again, or that the tumor inside Mom would kill her before New Year’s Day.