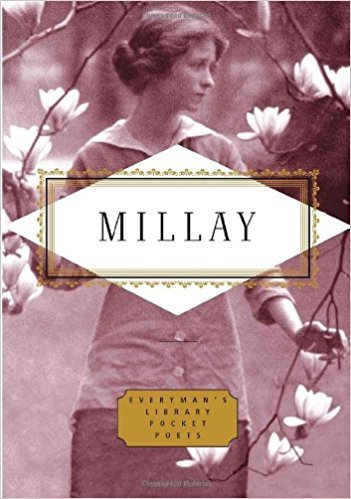

A Few Figs from Thistles by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1921)

Presented here is the full text of A Few Figs from Thistles: Poems and Sonnets by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892 – 1950). A Few Figs from Thistles was her second collection, published in 1921.

As a poet, Millay is considered as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre. Wildly popular, and actually famous as a poet in her lifetime, she’s no longer as widely read and studied, though still well regarded in the field of poetry.

The poetry in this collection explored love and female sexuality, among other themes. In the poems, including the oft-quoted “First Fig,” Millay both celebrates and satirizes herself.

Here are a few reviews, analyses, and commentaries on Millay’s inaugural published work, which is in the public domain:

Analysis on JStor

Bolstered by Thoughts

What’s Up with the Title?

Another Night of Reading

. . . . . . . . .

See also: 12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . .

A Few Figs from Thistles (1921) – full text

First Fig

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

. . . . . . . . .

Second Fig

Safe upon the solid rock the ugly houses stand:

Come and see my shining palace built upon the sand!

. . . . . . . . .

Recuerdo

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable—

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry;

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry,

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed, “Good morrow, mother!” to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, “God bless you!” for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

. . . . . . . . .

Thursday

And if I loved you Wednesday,

Well, what is that to you?

I do not love you Thursday—

So much is true.

And why you come complaining

Is more than I can see.

I loved you Wednesday,—yes—but what

Is that to me?

. . . . . . . . .

To the Not Impossible Him

How shall I know, unless I go

To Cairo and Cathay,

Whether or not this blessed spot

Is blest in every way?

Now it may be, the flower for me

Is this beneath my nose;

How shall I tell, unless I smell

The Carthaginian rose?

The fabric of my faithful love

No power shall dim or ravel

Whilst I stay here,—but oh, my dear,

If I should ever travel!

. . . . . . . . .

Macdougal Street

As I went walking up and down to take the evening air,

(Sweet to meet upon the street, why must I be so shy?)

I saw him lay his hand upon her torn black hair;

(“Little dirty Latin child, let the lady by!”)

The women squatting on the stoops were slovenly and fat,

(Lay me out in organdie, lay me out in lawn!)

And everywhere I stepped there was a baby or a cat;

(Lord God in Heaven, will it never be dawn?)

The fruit-carts and clam-carts were ribald as a fair,

(Pink nets and wet shells trodden under heel)

She had haggled from the fruit-man of his rotting ware;

(I shall never get to sleep, the way I feel!)

He walked like a king through the filth and the clutter,

(Sweet to meet upon the street, why did you glance me by?)

But he caught the quaint Italian quip she flung him from the gutter;

(What can there be to cry about that I should lie and cry?)

He laid his darling hand upon her little black head,

(I wish I were a ragged child with ear-rings in my ears!)

And he said she was a baggage to have said what she had said;

(Truly I shall be ill unless I stop these tears!)

. . . . . . . . .

The Singing-Woman from the Wood’s Edge

What should I be but a prophet and a liar,

Whose mother was a leprechaun, whose father was a friar?

Teethed on a crucifix and cradled under water,

What should I be but the fiend’s god-daughter?

And who should be my playmates but the adder and the frog,

That was got beneath a furze-bush and born in a bog?

And what should be my singing, that was christened at an altar,

But Aves and Credos and Psalms out of the Psalter?

You will see such webs on the wet grass, maybe,

As a pixie-mother weaves for her baby,

You will find such flame at the wave’s weedy ebb

As flashes in the meshes of a mer-mother’s web,

But there comes to birth no common spawn

From the love of a priest for a leprechaun,

And you never have seen and you never will see

Such things as the things that swaddled me!

After all’s said and after all’s done,

What should I be but a harlot and a nun?

In through the bushes, on any foggy day,

My Da would come a-swishing of the drops away,

With a prayer for my death and a groan for my birth,

A-mumbling of his beads for all that he was worth.

And there’d sit my Ma, with her knees beneath her chin,

A-looking in his face and a-drinking of it in,

And a-marking in the moss some funny little saying

That would mean just the opposite of all that he was praying!

He taught me the holy-talk of Vesper and of Matin,

He heard me my Greek and he heard me my Latin,

He blessed me and crossed me to keep my soul from evil,

And we watched him out of sight, and we conjured up the devil!

Oh, the things I haven’t seen and the things I haven’t known.

What with hedges and ditches till after I was grown,

And yanked both ways by my mother and my father,

With a “Which would you better?” and a “Which would you rather?”

With him for a sire and her for a dam,

What should I be but just what I am?

. . . . . . . . .

She Is Overheard Singing

Oh, Prue she has a patient man,

And Joan a gentle lover,

And Agatha’s Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,—

But my true love’s a rover!

Mig, her man’s as good as cheese

And honest as a briar,

Sue tells her love what he’s thinking of,—

But my dear lad’s a liar!

Oh, Sue and Prue and Agatha

Are thick with Mig and Joan!

They bite their threads and shake their heads

And gnaw my name like a bone;

And Prue says, “Mine’s a patient man,

As never snaps me up,”

And Agatha, “Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,

Could live content in a cup;”

Sue’s man’s mind is like good jell—

All one colour, and clear—

And Mig’s no call to think at all

What’s to come next year,

While Joan makes boast of a gentle lad,

That’s troubled with that and this;—

But they all would give the life they live

For a look from the man I kiss!

Cold he slants his eyes about,

And few enough’s his choice,—

Though he’d slip me clean for a nun, or a queen,

Or a beggar with knots in her voice,—

And Agatha will turn awake

While her good man sleeps sound,

And Mig and Sue and Joan and Prue

Will hear the clock strike round,

For Prue she has a patient man,

As asks not when or why,

And Mig and Sue have naught to do

But peep who’s passing by,

Joan is paired with a putterer

That bastes and tastes and salts,

And Agatha’s Arth’ is a hug-the-hearth,—

But my true love is false!

. . . . . . . . .

The Prisoner

All right,

Go ahead!

What’s in a name?

I guess I’ll be locked into

As much as I’m locked out of!

. . . . . . . . .

The Unexplorer

There was a road ran past our house

Too lovely to explore.

I asked my mother once—she said

That if you followed where it led

It brought you to the milk-man’s door.

(That’s why I have not traveled more.)

. . . . . . . . .

Grown-up

Was it for this I uttered prayers,

And sobbed and cursed and kicked the stairs,

That now, domestic as a plate,

I should retire at half-past eight?

. . . . . . . . .

The Penitent

I had a little Sorrow,

Born of a little Sin,

I found a room all damp with gloom

And shut us all within;

And, “Little Sorrow, weep,” said I,

“And, Little Sin, pray God to die,

And I upon the floor will lie

And think how bad I’ve been!”

Alas for pious planning—

It mattered not a whit!

As far as gloom went in that room,

The lamp might have been lit!

My little Sorrow would not weep,

My little Sin would go to sleep—

To save my soul I could not keep

My graceless mind on it!

So up I got in anger,

And took a book I had,

And put a ribbon on my hair

To please a passing lad,

And, “One thing there’s no getting by—

I’ve been a wicked girl,” said I;

“But if I can’t be sorry, why,

I might as well be glad!”

. . . . . . . . .

Daphne

Why do you follow me?—

Any moment I can be

Nothing but a laurel-tree.

Any moment of the chase

I can leave you in my place

A pink bough for your embrace.

Yet if over hill and hollow

Still it is your will to follow,

I am off;—to heel, Apollo!

. . . . . . . . .

Portrait by a Neighbor

Before she has her floor swept

Or her dishes done,

Any day you’ll find her

A-sunning in the sun!

It’s long after midnight

Her key’s in the lock,

And you never see her chimney smoke

Till past ten o’clock!

She digs in her garden

With a shovel and a spoon,

She weeds her lazy lettuce

By the light of the moon,

She walks up the walk

Like a woman in a dream,

She forgets she borrowed butter

And pays you back cream!

Her lawn looks like a meadow,

And if she mows the place

She leaves the clover standing

And the Queen Anne’s lace!

. . . . . . . . .

Midnight Oil

Cut if you will, with Sleep’s dull knife,

Each day to half its length, my friend,—

The years that Time takes off my life,

He’ll take from off the other end!

. . . . . . . . .

The Merry Maid

Oh, I am grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

I set my throat against the air,

I laugh at simple folk!

There’s little kind and little fair

Is worth its weight in smoke

To me, that’s grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

Lass, if to sleep you would repair

As peaceful as you woke,

Best not besiege your lover there

For just the words he spoke

To me, that’s grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

. . . . . . . . .

To Kathleen

Still must the poet as of old,

In barren attic bleak and cold,

Starve, freeze, and fashion verses to

Such things as flowers and song and you;

Still as of old his being give

In Beauty’s name, while she may live,

Beauty that may not die as long

As there are flowers and you and song.

. . . . . . . . .

To S. M.

If he should lie a-dying

I am not willing you should go

Into the earth, where Helen went;

She is awake by now, I know.

Where Cleopatra’s anklets rust

You will not lie with my consent;

And Sappho is a roving dust;

Cressid could love again; Dido,

Rotted in state, is restless still:

You leave me much against my will.

. . . . . . . . .

The Philosopher

And what are you that, wanting you

I should be kept awake

As many nights as there are days

With weeping for your sake?

And what are you that, missing you,

As many days as crawl

I should be listening to the wind

And looking at the wall?

I know a man that’s a braver man

And twenty men as kind,

And what are you, that you should be

The one man in my mind?

Yet women’s ways are witless ways,

As any sage will tell,—

And what am I, that I should love

So wisely and so well?

. . . . . . . . .

Four Sonnets

I

Love, though for this you riddle me with darts,

And drag me at your chariot till I die,—

Oh, heavy prince! Oh, panderer of hearts!—

Yet hear me tell how in their throats they lie

Who shout you mighty: thick about my hair

Day in, day out, your ominous arrows purr

Who still am free, unto no querulous care

A fool, and in no temple worshiper!

I, that have bared me to your quiver’s fire,

Lifted my face into its puny rain,

Do wreathe you Impotent to Evoke Desire

As you are Powerless to Elicit Pain!

(Now will the god, for blasphemy so brave,

Punish me, surely, with the shaft I crave!)

II

I think I should have loved you presently,

And given in earnest words I flung in jest;

And lifted honest eyes for you to see,

And caught your hand against my cheek and breast;

And all my pretty follies flung aside

That won you to me, and beneath your gaze,

Naked of reticence and shorn of pride,

Spread like a chart my little wicked ways.

I, that had been to you, had you remained,

But one more waking from a recurrent dream,

Cherish no less the certain stakes I gained,

And walk your memory’s halls, austere, supreme,

A ghost in marble of a girl you knew

Who would have loved you in a day or two.

III

Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow!

Faithless am I save to love’s self alone.

Were you not lovely I would leave you now;

After the feet of beauty fly my own.

Were you not still my hunger’s rarest food,

And water ever to my wildest thirst,

I would desert you—think not but I would!—

And seek another as I sought you first.

But you are mobile as the veering air,

And all your charms more changeful than the tide,

Wherefore to be inconstant is no care:

I have but to continue at your side.

So wanton, light and false, my love, are you,

I am most faithless when I most am true.

IV

I shall forget you presently, my dear,

So make the most of this, your little day,

Your little month, your little half a year,

Ere I forget, or die, or move away,

And we are done forever; by and by

I shall forget you, as I said, but now,

If you entreat me with your loveliest lie

I will protest you with my favorite vow.

I would indeed that love were longer-lived,

And oaths were not so brittle as they are,

But so it is, and nature has contrived

To struggle on without a break thus far,—

Whether or not we find what we are seeking

Is idle, biologically speaking.

The post A Few Figs from Thistles by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1921) appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.