An Interview with Richard K. Morgan

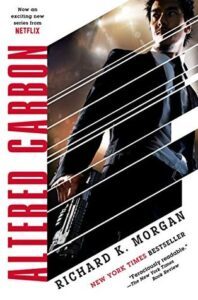

Richard K. Morgan is a Multi-talented bestselling author of the Takeshi Kovacs novels: Altered Carbon (2002), Broken Angels(2003), and finally, Woken Furies(2005). In Altered Carbon, the main protagonist Takeshi Kovacs is an ex-envoy now convict, downloaded into the body of a “nicotine-addicted ex-thug and presented with a catch-22 offer,” to discover who murdered the body of a billionaire in a locked room mystery. Kovacs is pulled into a never-dying society of the ultra-rich, where intrigue and conspiracy abound, and death means little if you have enough money. All set within a gritty and futuristic world. Broken Angels takes place thirty years later. Takeshi has again changed bodies, and now instead of a private investigator, he is a mercenary soldier, “and helping a far-flung planet’s government put down a bloody revolution.” Finally, in Woken Furies, Kovacs is back on his home of Harlan’s World, investigating Kovacs past relationships. Much to fans delight,

Altered Carbon was adapted to a Netflix series in 2018, starring Joel Kinnaman as Kovacs in season 1 and Anthony Mackie for season two.

In 2008, Morgan took a break from gritty science fiction with his series in A Land Fit For Heroes, starting with the first book, The Steel Remains, Morgan takes on a typical sword and sorcery novel but adds a gritty noir feel with more modern characters. “Ringil Eskiath—Gil, for short—a washed-up mercenary and onetime war hero whose cynicism is surpassed only by the speed of his sword.”

Additionally, Morgan has written more award-winning science fiction in the Black Man novels, first with Thirteen (2007) and Thin Air (2018.)

In the back and forth conversation below, Richard answers questions regarding the hero myth, influences, cancel culture, and more.

Your first novel Altered Carbon is the story of an envoy, now-convict Takeshi Kovacs. It created its own genre with a combination of the hard-boiled noir of Raymond Chandler and William Gibson’s Neuromancer’s feel. Did either of these writers influence you?

Very much so, yes. Gibson’s short stories in Omni Magazine in the early eighties were a crystallising moment for me – the moment I realised This! This is the sort of thing I want to write! The Chandler influence came later, and was consequent; everyone was referring to Gibson as The Chandler of SF, so I wandered over into the crime genre looking for this guy Chandler, to see what he was about. After that, I never looked back!

Cyberpunk as a genre came to mainstream attention in the early 1980s with Blade Runner and Neuromancer by William Gibson, though arguably, it is seen in the earlier works of Phillip K. Dick. Either way, cyberpunk is the evolution of technology, leading to a dystopic future. Where do you think cyberpunk is going as a genre in the future?

I don’t know that cyberpunk is “going” anywhere, any more than its non-SF antecedent “noir” has ever “gone” anywhere. I think in both cases what has ended up identified as a subgenre is in reality more of an aesthetic or, in musical terms, a backbeat. Cyberpunk showed up in the eighties as a conscious rejection of both the Big Shiny Futures of the Golden Age (an easy enough target!), but also the weird-ass speculations of the New Wave. CP was eminently pragmatic in both its approach to technology and to socio-political trends. Look, it said, Here’s some cool new tech, and look how little it’s actually changed the way humans behave. Cyberpunk insisted, in much the same way as noir, that we are our own worst enemies, that there aren’t really any Good Guys or Bad Guys, and that the human condition has some uncomfortable eternal verities to which we’ll likely always be subject. And to be honest, those were assumptions that had been kicking around in mainstream literary fiction for a very long time indeed. There is, in fact, a case to be made that all Cyberpunk really represented was the final unavoidable seepage of that modernist literary aesthetic into the rarified ghettoes of genre (just as the New Wave had smuggled in experimental writing a decade or so earlier). So, while there’s been a lot of talk about The Death of Cyberpunk, or how The Cyberpunk of Today Just Ain’t The Same As The Cyberpunk of Yesteryear (a sort of genre-based “Today’s Music Ain’t Got The Same Soul” whinge), the truth is that the aesthetic of Cyberpunk has taken the world by storm, sunk into every aspect of it at every level, and endures as a major defining factor in the stories that we continue to tell, not only in genre but across the whole literary firmament.

There has been quite a lot of societal and political upheavals in the world this year. Do you think that this year will affect your writing in the future? And if so, how?

It probably will at some point, but it’s hard to say how right now. I find that any new input needs to marinate for a while before I find a use for it. The car lease agreement I signed that triggered the idea of the sleeve rentals in Altered Carbon was something I encountered in Vancouver back in early 1991. It didn’t crop up in my writing until some time in ’93 or ’94. The argument I had with a buddhist that underlies the main storyline in the same novel happened even earlier. So yeah, all the shit that 2020 brought in will likely make its way into my fiction somewhere down the line, but as to when and how – watch this space!

I remember reading about that argument with a Buddhist, and I found that your statement, ‘So I’m suffering and I can’t remember what I did to earn this suffering? That’s not right, is it, because I’m not that person?’ And he said: ‘It’s the same soul.’ I said: ‘It doesn’t fucking matter. What matters is whether you, as an experiential being, remember it. Otherwise, I’m being punished and I don’t know why. That’s the height of injustice.’” to be true. It is the height of injustice when distilled like that as an idea and I can see how that reflected in Takeshi Kovacs. What other broad concepts would you like to tackle someday?

I remember reading about that argument with a Buddhist, and I found that your statement, ‘So I’m suffering and I can’t remember what I did to earn this suffering? That’s not right, is it, because I’m not that person?’ And he said: ‘It’s the same soul.’ I said: ‘It doesn’t fucking matter. What matters is whether you, as an experiential being, remember it. Otherwise, I’m being punished and I don’t know why. That’s the height of injustice.’” to be true. It is the height of injustice when distilled like that as an idea and I can see how that reflected in Takeshi Kovacs. What other broad concepts would you like to tackle someday?

I think if we’re talking about broad moral concepts, I tend to mix the same basic palette into most of what I write – I’m concerned above all with injustice and human stupidity, and Buddhism, for all its superficially non-judgemental appeal, is still a religion, still an example of human stupidity. (Not sure on this? Go ask the Rohyinga). My protagonists tend to be exasperated with the world, because I am too – as Quellcrist Falconer puts it “The human eye is a wonderful device; with a little effort it can fail to see even the most glaring injustice.” The brutality we cheerfully inflict on our fellow humans in the scramble for ascendancy, the self-serving lies we tell about it, the sheer infantile cognitive dissonance of the dynamic – that’s the enduring texture of the backdrop my stories tend to play out against.

You have written both a fantasy series in A Land Fit for Heroes and genre-bending series in Takeshi Kovacs and the novel Thin Air. Is the process of writing a fantasy novel different than a science fiction one?

For me, it wasn’t. In fact, I’d made myself something of a tacit promise that I’d simply hump all the usual noir furniture from my SF work over the fence into the field of fantasy and see how it panned out. Turns out it works there pretty much as well as anywhere else