Hunger on the Wing (Conclusion)

One afternoon I looked in on the six or seven grasshoppers Ihad in separate jars and found that they had done something interesting. Wetorange strands, about the thickness and texture of a braided bootlace, lay intheir jars. A day or two later, I saw one of my captives in the act ofproducing such a strand. It pressed its hind end against the floor of the jarand arched its back, as if exerting downward pressure, and an orange strandsqueezed out from the rear, like toothpaste from a tube. This strand lookedslimier and smoother than the others I'd seen but was recognizably the samething. By the next day it had dried to look exactly like the other hoppers'strands, the pattern of its texture emerging as it dried. A day later it wasdry enough to see that what had appeared to be individual strands woventogether were merely dozens of pieces, shaped like sesame seeds, arranged in anorderly overlap—eggs, of course.

In Missouri in the 1870s, the egg masses of Rocky Mountainlocusts lay so thick in the beds of rivers and creeks that authorities offereda five-dollar bounty per bushel of them. This species, the only grasshopper inNorth America that typically shifted into the locust phase, had swarmed forhundreds of years, as proved by layers of locusts in glaciers dated at around750 years old. Presumably, they had swarmed for millennia before that. Butaround 1880 the swarms abruptly ceased, and the species went extinct. The lastlive specimens were collected in 1902.

No one knows why the Rocky Mountain grasshopper vanished,but changes in habitat are the most likely reason. In the late 19th century,the bison was virtually exterminated, as were the native peoples. Settlersdrastically reduced the numbers of beaver in the Rocky Mountains, removing animportant control on flooding. Cattle brought in by ranchers grazed andtrampled the riversides, and farmers plowed up their fertile soil. To fight offthe locusts, farmers tried all sorts of control measures, from contraptionscalled "hopperdozers" and controlled fires to fasting and prayer.What actually worked was to carry on farming. Plowing devastated the RockyMountain locust population, as did the planting of exotic trees, which broughtin many new predatory birds.

Hundreds of other grasshopper species thrived despite, oreven because of, these habitat changes. But according to Jeff Lockwood, anentomologist at the University of Wyoming, the Rocky Mountain grasshopper'snesting habits made it particularly vulnerable. (Many species prefer grassyhillsides for nesting sites.) The Rocky Mountain locust's boom-and-bustpopulation cycles also put it at risk. Despite the vast areas attacked byswarms—from Manitoba to Texas and from Wisconsin almost to the West Coast—thelocust's home base, the area where it could always be found in plague years aswell as other times, was a much smaller area in the northern Rockies.European-American settlement there quickly dispatched the species. It's theonly known case of a pest species exterminated by human action, and it was anaccident.

The extinction went unnoticed for a few decades—that such afecund creature could abruptly vanish was counterintuitive—and unmourned. Thefocus of 19th-century science was killing pests, not appreciating them. Westill don't know what effect the extinction has had. The swarms causedwidespread nutrient recycling and large-scale habitat disruption. CharlesBomar, an insect ecologist at the University of Wisconsin at Stout, hasspeculated that they served as some sort of cyclic ground clearing, much likeforest fires. But specific effects are difficult to substantiate, and no onehas proved any related extinctions.

Even the basic facts are in dispute. Daniel Otte, thecurator of entomology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia,suggests the Rocky Mountain locust is not extinct at all but has simplyrefrained from swarming in recent times, perhaps because of encroachingagriculture. Otte points out that almost no one can distinguish closely relatedgrasshopper species by sight. In fact, the integrity of the Rocky Mountainlocust, Melanoplus spretus, as a distinct species has only recently beendemonstrated through genetic analysis. The characteristics that distinguish M.spretus from its close, and still living, cousin Melanoplussanguinipes (the migratory grasshopper) are its proportions. Identifyingan M. spretus involves taking its measurements—the length of thevarious leg segments, for example—and comparing them with published figuresderived from statistical analysis. To complicate this problem, no one is surewhat the solitary phase of M. spretus looked like. The very idea ofgrasshoppers shifting phases came about just as M. spretus was dyingout. It's possible, Otte says, that Rocky Mountain locusts are nibbling at yourlawn right now, unrecognized. More likely, they're hidden in remote rivervalleys, reduced in number but still thriving.

This apparent extinction, far from creating a domino effectof further losses, may have created an opportunity for other grasshopperspecies. The red-legged grasshopper (Melanoplus femurrubrum), whichwas responsible for newsworthy outbreaks in Idaho in 2001, thrives on groundbroken by agriculture and other human endeavors. Its numbers have grown muchlarger since the extinction of its cousin. In 2002, patchy outbreaks ofclear-winged grasshoppers (Camnulla pellucida) in Colorado attaineddensities of 200 per square yard; a tenth of this number is considered a dangerto crops. Scientists have had some success in developing toxins andparasite-laden baits to combat grasshopper outbreaks. But applying pesticideson broad stretches of land has rarely proved cost-effective. Some pesticidesseem to make future outbreaks worse, because the predator and parasitepopulations they affect don't recover from the poisoning as fast as thegrasshoppers do.

Even though existing North American grasshopper speciesdon't migrate as readily as the Rocky Mountain locust did, some of them doswarm in less dramatic migrations. And their swarming potential may have moreto do with circumstances than with any inherent limitations. Bomar suggeststhese other species, especially the red-legged grasshopper and the migratorygrasshopper, are stepping into the niche the Rocky Mountain locust vacated. Hissuggestion brings back uncomfortable memories of the giant I found in mydriveway. "The potential for swarms is there," Bomar says."Eventually, one of these micropopulations is going to move out."He's intrigued by the scientific opportunity such an event would present. Forthe rest of us, it may be the return of an ancestral nightmare.

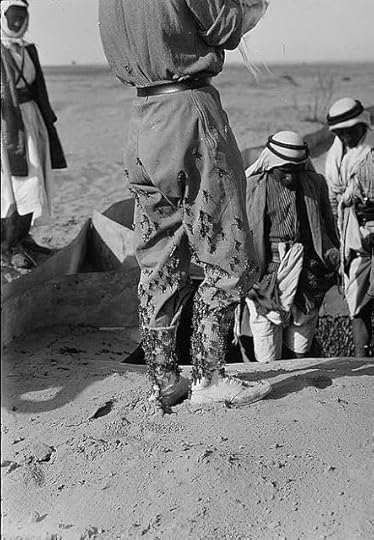

African locusts herded into a trap

African locusts herded into a trap A pitful awaiting immolation

A pitful awaiting immolation

Published on February 01, 2012 09:00

No comments have been added yet.