Hunger on the Wing (Part 2 of 3)

The most vivid firsthand account of swarm behavior is surelythat of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the children's writer who chronicled the life ofher family on the American frontier. By 1874 Wilder's restless father had movedthe family to a homestead near Walnut Grove, Minnesota. Wilder vividly paintsthe heat of that summer: The edge of the prairie "seemed to crawl like asnake" with heat shimmer, and the pine boards of buildings dripped theirviscous sweat. The family's wheat crop, which promised to yield generously, washead-high. Then a cloud dimmed the day, moving in without wind. Its individualparticles glittered. The falling insects sounded like a hailstorm, and thissound was succeeded by the multitudes chewing (like the working of thousands ofscissor blades, some witnesses said). Prairie grasses and wheat and oat cropsvanished; beets, beans, potatoes, carrots, and corn were razed; willow and plumtrees were shorn. (Although the Ingalls family didn't grow these crops, othersnoticed the insects preferred to start with tobacco and onions when these wereavailable.) "Not a green thing was in sight anywhere" after a fewdays, Wilder concludes, echoing the Book of Exodus.

Only the family's chickens benefited, snapping up thewindfall of easy prey. (Some writers of the period noted that the chickens tookon the flavor of grasshoppers, and that they and their eggs became inedible.Others wrote that the grasshoppers themselves were edible, though the Ingallsfamily does not seem to have taken an interest in this option.) The family fellon hard times, and at night they could hardly sleep for the sensation ofcrawling on their skin. On Sunday they arrived at church with their bestclothes crawling with grasshoppers and stained with their brown spittle. Themeager creek thickened with scum, and the land twitched with dust devils. Thecow's milk went bitter and nearly dried up.

Today's American infestations are minor compared with swarmslike those, but they still devastate wide areas from the Pacific Northwest tothe Great Plains. About 2 million acres of Colorado have been eligible fortreatment against grasshoppers in a single year, and it is not uncommon forseveral counties at a time to be affected by infestations. In an ordinaryseason, grasshoppers eat about 20 percent of the fodder on rangeland; in areasof infestation, the percentage can increase to 100, affecting millions of acresat $5 to $10 per acre. On cropland, the devastation is even greater.

Although the Rocky Mountain locust, the species that wreakedhavoc here in the 19th century, does seem to have disappeared, its ecologicalniche may be only temporarily vacant.

At rest, the red-legged grasshopper, a close cousin of theRocky Mountain locust, looks vaguely mechanical. Two immense eyes take up thesides of its head. Roughly between these are three smaller eyes and a pair ofshort antennae. The hard, yellow-green underside of its thorax is marked withdeep indentations that resemble smiley faces doubled and distorted in mirrors.The abdomen is segmented. The rear of it ends in four blunt appendages closedtogether like pinching fingers. When the insect takes flight, its vitality isrevealed. The camouflaged forewings open to show the vivid hind wings, whichflutter loudly and too fast to be seen distinctly. The specialized hind leg isa marvel of complexity. It possesses sensory equipment as well as a comblike projectionused by the male to coax music from his wings, and its muscles are powerfulenough to accomplish some of the most impressive leaps, proportionallyspeaking, in the animal kingdom.

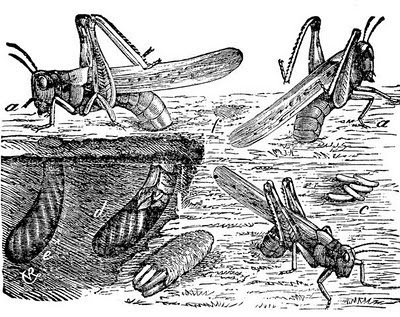

Rocky Mountain locusts laying eggs in topsoil

Rocky Mountain locusts laying eggs in topsoilMuch of the grasshopper's insides are taken up byreproductive equipment. The female's ovaries produce rows and rows of eggs,which are attached by stemlike parts to each other. The effect is somethinglike an orderly bunch of grapes, lined up mostly in neat rows, and glisteningwith moisture. However, the naked eye is impressed mainly by the fat blackstrand of digestive tract. Narrower in spots and girdled with knotty, fibrous projectionsnear the middle, it is essentially a tube. The dark color is that of chewedvegetation. At any given time, a substantial proportion of the grasshopper'sbody weight is its unconverted food. When a grasshopper is eaten by a mantis,the mantis typically eats around this unattractive vegetation. It is leftholding the digestive tract, which resembles the stick at the center of a corndog.

That summer in Oklahoma, I caught some grasshoppers in jarsand fed them on weeds and grasses. They ate avidly, leaving nothing of myofferings. Their mouths had toothed jaws with multiple points of articulation,a complex arrangement that appeared to constitute two or three mouths workingat once. In fact, this equipment allowed them to chew both vertically andhorizontally. Typically, they chewed along a blade of grass, creeping up theblade several inches before going deeper. Or they chewed a hole through theblade, then expanded the hole until the blade was cut in two and it collapsed.

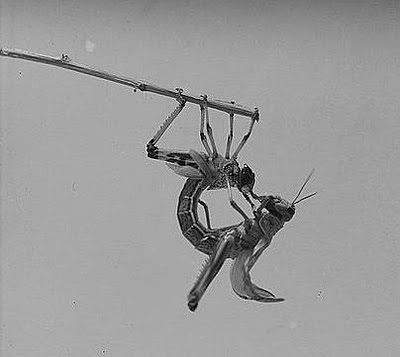

The jars didn't suit them: They were heavy, humid creatures,and in a day or two the glass was fogged with condensation, the bottom of thejar laden with their conical black feces and their spit. They died off quickly,even when placed in more commodious accommodations. I tossed a grasshopper intothe web of a black widow spider, assuming the spider would dispatch it quickly.Instead, the grasshopper's energetic struggles wrenched it loose from the web,though at the cost of a hind leg. I repeated this experiment with a differentindividual. This time the grasshopper's leaps freed it easily, and furtherleaping knocked the spider from its web. The spider lay on its back, kickingfrantically, as the grasshopper chewed its front leg.

It's such hunger that drives a locust swarm. A single desertlocust can eat its own weight in a day. Multiplied by a billion, this hungermay be the most demanding our planet has known. The mechanisms behind thebehavioral change from solitary grasshopper to swarming locust are not wellunderstood. In the laboratory, scientists have been able to provokegrasshoppers into a phase shift by pelting them with wads of paper for hours onend. This result suggests that the jostling the grasshoppers experience in agroup prompts the phase shift. Stephen Simpson of the University of Oxford has locatedthe hardwiring for this mechanism more precisely on the insects' hind legs. Aspot there (which Simpson calls "the G-spot—G for gregarization") isthe trigger that somehow provokes morphological changes. (Other research, nowlargely disproved, pointed toward pheromones found in the feces, most likelyproduced by gut-dwelling bacteria, as the stimulus to change.) It may be thatmultiple cues are involved, and perhaps different locust species use differentcues.

Population explosions occur in various animal species, fromrabbits to mayflies. Vast migrations occur in creatures as diverse as monarchbutterflies and wildebeests. But the phase shift and swarming of grasshoppersappears to be unique. It may provide a way to survive and reproduce when foodsupplies dwindle. In Africa, the desert locust's eggs can lie dormant in aridsoil for several years until rain triggers their hatching. The hatchling nymphsthrive on the brief lushness that desert rains bring. When they've devouredeverything in an oasis, they swarm to reach green regions beyond the desert. Inthe case of the Rocky Mountain locust, however, the swarming is moremysterious. These locusts never seemed to establish permanent populationsbeyond their home base in the Rockies.

When the young of swarming locusts hatch, they, too, areswarming locusts. The ability of grasshoppers to inherit traits their parentsacquired was once a puzzle, for it seems to bypass the gradual genetic changethat the theory of evolution predicts. Some entomologists describe thisphenomenon as "cultural": The mother locust supplies her eggs with aheavier dose of nutrients and a chemical—called a maternal gregarizingagent—that encourage her offspring to develop toward the gregarious end of itspotential. The environment into which it hatches (the jostling swarm itself)also constitutes a cultural influence. Such nongenetic inheritance is notunique; it has been observed in human populations when, for example,consistently good nutrition over several generations prompts an increase inaverage stature. The offspring of locusts born in a subsequent season may ormay not develop into locusts; crowding is the deciding factor.

Published on January 31, 2012 09:00

No comments have been added yet.