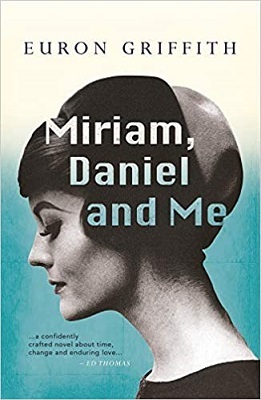

Review of Miriam, Daniel and Me by Euron Griffith, pub. Seren Books 2020

"The driver started the engine and the Ford Anglia pulled off. In the mirror, Miriam watched Pantglyn fall away like something suddenly cut loose. They were going to pick up the suitcases to go on their honeymoon. Daniel had booked a weekend in London.

On the Saturday he took her to Stamford Bridge to see Chelsea play Arsenal."

Griffith is not a new writer; he has published four novels in Welsh (one for children) and a short story collection in English, The Beatles in Tonypandy (Dean Street Press 2017). I still recall reading the title story of that collection, back in his student days, and wondering if I’d ever read a funnier or more inventive long short story. This, however, is his first novel in English, concerning three generations of a North Wales family.

Given his previous experience, it isn’t altogether surprising that his narrative techniques provide a lot of the interest, two of them in particular. The story is not linear; it switches back and forth between generations quite a lot and hence between points of view – the “me” of the title, Daniel and Miriam’s son, is a first-person narrator of what he himself sees, but other people’s experiences are told in close-third. The switches of time and viewpoint may at first seem arbitrary but are in fact carefully orchestrated; their effect is that we see events first and only later find out what lay behind them; we meet people but then get to know them better. For instance, we learn that Miriam’s friend Leah was proposed to in a rather odd and unexpected way; only much later do we find out why – rather as she may have done herself.

In addition, the chapters are very short. Few extend over more than three pages; many are shorter, one is half a page. They are vignettes, brief glimpses into people’s lives. The net effect of both this and the non-linear narration is to create the effect of autobiography, of a person finding out about his past via family anecdotes and disconnected memories and later filling the story out with information he finds elsewhere. I don’t know, incidentally, whether the story is in fact autobiographical, nor do I think it matters; the point is to create the effect of autobiography, which these techniques succeed well in doing. Only in chapter 51, where we are temporarily misdirected about the identity of someone who has died, did I feel the device was misdirection for its own sake.

The boy-narrator (unless I missed it, we never do learn his name) grows up in the sixties and the protests against the 1969 investiture of Charles as prince of Wales play a part in the narrative. The atmosphere and idiom of the period are well evoked; he has the details off pat, the right TV programmes, cars, wished-for toys, and this accuracy inclines me to believe he has the details of the earlier periods, which I can’t vouch for personally, right as well. It doesn’t sound like knowledge he had to “research”, either (which is of course how research in fiction ought to come across). The child-voice is convincing too.

One warning: if you are one of those readers, and I count myself among them, who would rather avoid any fictional depiction of cruelty to animals, you will want to skip chapters 29 and 49. This is easily done. They are self-contained, concern a minor character and avoiding them will not materially affect your reading of the novel. I don’t say they are completely irrelevant; they are probably there to establish gritty rural realism or whatever, but I wouldn’t say they were essential either.

Running alongside Miriam’s actual story is one that never happened, a direction her life might have taken but didn’t. This fades as her real life takes over but resurfaces at the end, in a conclusion which is the more moving for not being wistful or sentimental: things are as they are and it is pointless to idealise what might have been at the expense of what was.

By the way, if you can still get hold of his short story collection. The Beatles in Tonypandy, pub. Dean Street Press 2016, and there’s a kindle edition as well, do! That title story is still one of the most entertaining I’ve ever read.