September 1, 1961 – Eritrean nationalists attack Ethiopian police posts

On September 1, 1961, insurgents of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) stormed a number of police posts in western Eritrea, marking the start of the Eritrean War of Independence, a protracted conflict that would last three decades. The insurgents subsequently carried out more attacks against security forces. In the period that followed, the ELF gained local support in its areas of operations in the rural Muslim-populated rural northern and western regions of Eritrea and increased its numbers with the inflow of many new recruits. The rebels also increased their frequency of attacks against police targets, primarily to capture much-needed weapons. By June 1962, the ELF had some 500 fighters, which included some police defectors who took along their weapons and ammunitions. At this time, Muslims formed the vast majority of the ELF, which also advocated a pro-Muslim, pro-Arab ideological and religious struggle against the predominantly Christian Ethiopia. Also for this reason, the ELF gained some military and financial support from a number of Muslim countries, including Syria, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

On May 24, 1991, Eritrea

gained its independence from Ethiopia

following a 30-year armed revolution. Ethiopia

had annexed Eritrea

as a province in November 1962, inciting Eritrean nationalists to launch a

rebellion. Following the war, as Eritrea was still legally bound as part of

Ethiopia, in early July 1991, at a conference held in Addis Ababa, an interim

Ethiopian government was formed, which stated that Eritreans had the right to

determine their own political future, i.e. to remain with or secede from Ethiopia.

Then in a UN-monitored referendum held in April 23 and 25,

1993, Eritreans voted overwhelmingly (99.8%) for independence; two days later

(April 27), Eritrea

declared its independence. In May 1993, the new country was admitted as a

member of the UN.

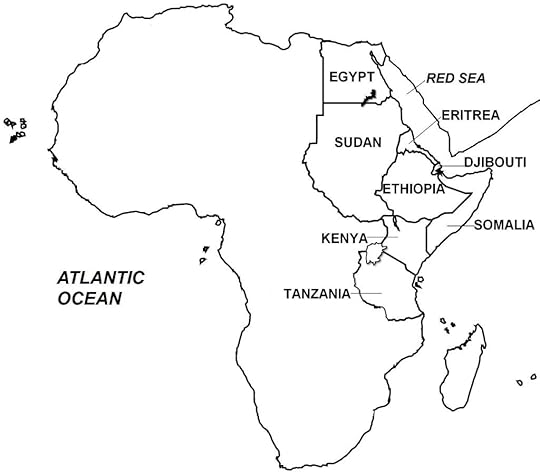

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries(Taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In

September 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set up

by the Allied Powers (Britain,

France, Soviet Union, and United States),

failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter to

the United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much of

its history, Eritrea

was not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of and

subordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable of

surviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, various

countries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italy

wanted Eritrea returned, to

be governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, an

arrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland.

The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such,

called for Eritrea

to be granted its independence. Britain,

as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regions

to be incorporated into Ethiopia

and the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, the

Ethiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and cultural

ties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through the

Red Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United States

influenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S. government saw Eritrea

in the regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist

(Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East. Unbeknown to the general public at the time,

a U.S. diplomatic cable from

Ethiopia to the U.S. State

Department in August 1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as

75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea to

determine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings to

the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, which

was strongly influenced by U.S.

wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) that called for establishing a loose federation

between Ethiopia and Eritrea to be facilitated by Britain and to be realized no later

than September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently was implemented,

allowed Eritrea

broad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative,

police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation

would affirm the sovereignty of the Ethiopian monarch whose government would

exert jurisdiction over Eritrea’s

foreign affairs, including military defense, national finance, and transportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea elected

a 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christians

and Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by the

UN. Just days before the September 1952 deadline for federation, the Ethiopian

government ratified the Eritrean constitution and upheld Eritrea’s Representative Assembly

as the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-Eritrean

Federation was established, and Britain

turned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’s

head of government (called Chief Executive who was elected by the Eritrean

Assembly) was forced to resign, and successors to the post were appointed by

the Ethiopian emperor. Ethiopians were appointed to many high-level Eritrean

government posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorship

was imposed. Amharic, Ethiopia’s

official language, was imposed, while Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s main languages, were

replaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses were

moved to Ethiopia, while

local tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia.

By the early 1960s, Eritrea’s

autonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the Eritrean

Assembly, under strong pressure from Emperor Haile Selassie, dissolved the

Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation and voted to incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s

14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civilian

dissent in the form of rallies and demonstrations broke out, and was dealt with

harshly by Ethiopia,

causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations with

security forces. Opposition leaders, particularly those calling for

independence, were suppressed, forcing many to flee into exile abroad; scores

of their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organized

resistance to Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestine

Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles in

Sudan.

At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some 40,000 members who organized in cells

of 7 people and carried out a campaign of destabilization, including engaging

in some militant actions such as assassinating government officials, aimed at

forcing the Ethiopian government to reverse some of its centralizing policies

that were undercutting Eritrea’s autonomous status under the federated

arrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissident campaigns

had weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist, albeit

with limited success. Also by 1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization,

the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July

1960 by Eritrean exiles in Cairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had as

its objective the use of armed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence.

In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “Supreme

Council”, operated out of Cairo

to more effectively spread its political goals to the international community

and to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.