Second dispatch from the mystic abyss

Cyril Kuhn, "Wagner."

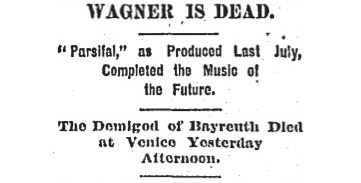

Where to start? With Wagnerism, the point of departure was clear from the outset: Wagner's death at the Palazzo Vendramin, in Venice, on February 13, 1883. There is nothing innovative in beginning a book with a major figure's death, but the import of my three-thousand-word evocation of the worldwide memorials for the composer is less retrospective than predictive: it is in the memorializing of Wagner that the manifold and conflicting strains of Wagnerism, the phenomenon of Wagnerian influence, immediately become visible. Everyone agrees that Wagner was important, but no one remembers him, cherishes him, or condemns him in quite the same way. The so-called Meister dematerializes into competing projections of his work. The noise of his own funeral drowns him out.

From the narrative standpoint, it's useful to begin a large-scale book of this kind not with abstract claims but with an exemplary scene that enfolds certain themes and introduces certain characters. (I think of it as the Barbara Tuchman maneuver — the funeral of Edward VII at the outset of The Guns of August.) My first book, The Rest Is Noise, opens with the Austrian première of Salome in Graz in 1906 — an episode that allowed me to bring on stage Strauss, Mahler, Puccini, Schoenberg and his students, Adolf Hitler, and the protagonist of Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus. Indeed, I chose that setting precisely because the great novelist had gone there before me. With Wagnerism, Mann is again directing behind the scenes. He was undoubtedly thinking of Wagner when he titled one of his most famous stories Death in Venice, even if the composer goes unnamed in that text. And so my Prelude — a nod to Wagner's favored way of beginning an opera — is called "Death in Venice."

As the news of Wagner's death travels the world, we see such diverse figures as Verdi, Mahler, Nietzsche, and Swinburne reacting to it. Sarah Butler Wister's vivid description of a memorial concert in Paris conveys the contentious atmosphere that surrounded the composer even as an attempted deification process was under way. Particularly important is the ominous scene that attended a students' memorial at the Sophiensaal in Vienna — one at which antisemitic rhetoric surfaced, as the Neue Freie Presse noted. That event allows me to introduce the figure of Theodor Herzl, who resigned from the Albia fraternity in protest of the anti-Jewish outbursts. That Herzl loved the music nonetheless confronts us with Wagnerism in its most complex form — the partly alienated fascination of those whom the composer would have regarded as an inferior racial other. W. E. B. Du Bois appears in the introduction in the same guise.

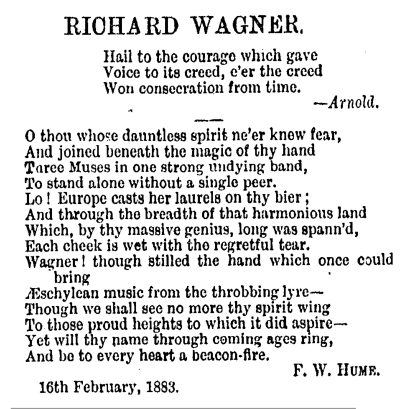

From the Dunedin Evening Star.

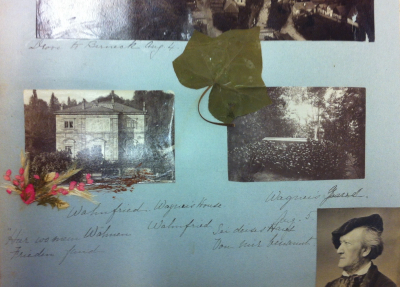

The composition of the prelude required a synthesis of a hundred or more far-flung sources. Much of the research was done without having to leave my desk: mass digitization of newspapers and magazines has exposed the daily fabric of the past to a remarkable degree. In the course of one roaming search I found a Wagner sonnet from Dunedin, New Zealand — a sign of just how far the sorcerer's spell reached. Having noticed that late-nineteenth-century pilgrims made a habit of collecting souvenirs from Wagner's grave in Bayreuth, I found examples in the Isabella Stewart Gardner archive in Boston, the online holdings of the Österreichischer Nationalbibliothek, Éric Lacourcelle's biography of Emanuel Chabrier, and Upton Sinclair's novel King Midas. (In the last, a Wagner pebble disgusts a Brahmsian customs officer.) When it came to Wagner himself in Venice, I relied on the meticulous researches of John W. Barker, who has written not one but two entire books about the composer's relationship with the city, building on Henry Perl's Richard Wagner in Venezia.

Isabella Stewart Gardner's Wagner ivy.

Crucially, I was able to visit the Palazzo Vendramin itself in 2011, during an idyllic month when I was based the American Academy in Rome. Alessandra Althoff Pugliese of the Associazione Richard Wagner di Venezia gave me a tour of the Wagner quarters, During the same period, I blew a certain amount of money on a sea-facing balcony room at the Grand Hotel Excelsior Vittoria, in Sorrento, where Wagner stayed at the time of his final meeting with Nietzsche. This sort of Wagner tourism may not have been strictly necessary to the writing process, but it gave me a certain confidence. Furthermore, various characters in my story had themselves gone on such journeys. Both William Butler Yeats and Andrei Bely went to the trouble of visiting the Grand Hotel et de Palmes, in Palermo, where the score of Parsifal was finished. Alain Locke once took Langston Hughes on a tour of Wagner sites in Venice — in the course of an attempted and apparently unsuccessful seduction.

The author's most Wagnerian moment, in Sorrento.

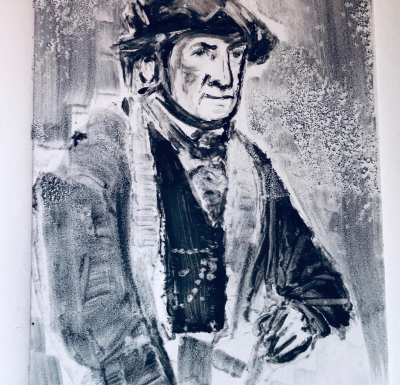

As I traveled for The New Yorker over the past decade, I was constantly on the Wagnerian prowl. Visiting museums in various cities, I gravitated toward the Symbolist galleries, where something Wagnerish almost invariably lurked. I toured German Wagner cities — Leipzig, Dresden, Munich, and, of course, Bayreuth — and stopped at the sacred-kitsch sites of Ludwig II in Bavaria, including the Starnbergersee, where his body was found. (It is no accident that the Starnbergersee shows up in The Waste Land, a poem wet with Wagnerian allusion.) I went to the Goetheanum in Dornach, which Rudolf Steiner described as a second Bayreuth. And I made several visits to the Wagner sites in Lucerne and Zurich. If Wagnerism has a spiritual home, it is in Zurich, where James Joyce and Thomas Mann, two skeptical Wagnerians, lie buried a few miles from each other. Zurich also happens to be the native town of my friend and German tutor Cyril Kuhn, who was of inestimable help in the final stages of the book. His linotype of Wagner appears at the top of the post.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers