Un-Gendering Racial Violence: Remembering Mary Turner by Stephane Dunn

Un-Gendering Racial Violence: Remembering Mary Turner

By Stephane Dunn | @DrStephaneDunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The year was 1918.

Mary Turner, a young Black woman near Brooks and Lowndes County, Georgia, protests the unjust killing of her husband Hayes. He was lynched with other innocent Black folk when a white mob rampages over the murder of a violent plantation owner. Mary is eight months pregnant. The White men show no mercy because of her gender or pregnancy.

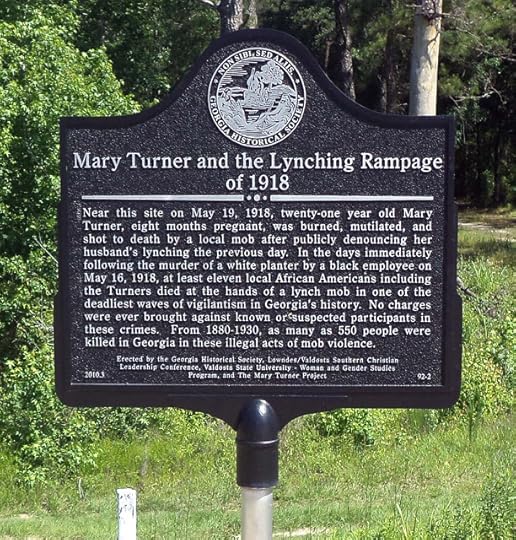

They string Mary up on a tree near where they killed her husband. They pour gasoline on her and burn the clothes off her body. One White man takes a knife and slits her abdomen. Her baby falls out and cries; they stamp the baby’s head to death. Still not satisfied, they riddle her body with bullets. A frequently vandalized marker where she was murdered is one of the few tangible public representations.

I visited the marker for Mary Turner on a road trip with my family from Georgia to Florida about seven years ago. It was shrouded in weeds. A dead rabbit and litter lay around it. The marker was bullet ridden. We reported it. I haven’t stopped there since, but Mary stayed with me.

Black Women and their inequitable fate in racial violence and oppression has slowly begun to garner more major attention. In the wake of Ahmaud Arbery’s recorded murder, The New York Times article, “Ahmaud and the Ghosts of Lynchings” references Mary Turner in placing the murder of Ahmaud Arberry in historical context. It unintentionally suggests what has been the place for black women in the public discourse about racial terror against black people.

Mary is one of the ghosts, a metaphor for how Black female victims of racial violence continue to be positioned in news media, political speech and, painfully, in our collective outrage. For me, the Mary Turner story presents two tragedies, the first is her lynching all those years ago. The second is that neither her name or story is widely known, and that’s the case for too many Black female victims.

Why is the racial violence against Black men the preeminent, de facto public representation? In large part, it’s because the gendering of the Black freedom struggle historically privileges physical, social, and political assaults on black manhood as the ultimate denial of personhood and freedom, placing Black men’s oppression at the center of public discourse about racial violence.

Black women remain secondary stories despite the lengthy history of them being killed, battered, and tortured by police and white men protected by police, including recent victims Sandra Bland, and now Breonna Taylor and Atatiana Jefferson. Their murders failed to incite the potentially transformative fury that has followed the unjust killings of Black men.

The gendered nature of the Black rapist myth used to justify killing Black boys and men amplified racial violence. However, the terrorization of the Black body has always been shared by Black girls and women, victims of white people’s right of way to beat, kill, and rape them with impunity.

As Dr. Kimberlè Williams Crenshaw has highlighted a number of times, including in the recent “Naming the Threat,” this invisibility is deeply problematic and contradicts the ethos of Black Lives Matter. Crenshaw founded the African American Policy Forum, a think tank that launched the “Say Her Name” campaign several years ago to highlight black women victims of police violence and the lack of attention.

Viral videos have helped to make the recent murders of black men high profile cultural triggers. Arbery and George Floyd are the newest two. In 1955, Mamie Till forever ingrained her young son Emmet Till on our historical memory. She famously insisted on an open casket and allowed photos of her 14-year-old son’s tortured body. We saw Rodney King being beaten by police in ’91. It ignited a firestorm literally. Now, we see a white police officer pressing his weight on George Floyd’s neck as his nose bleeds and he begs for his life. We saw Eric Garner dying while officers participate or stand nonchalantly around and an unarmed Arbery being hunted then shot to death.

The same is not true for Black female victims of white male police or vigilantes whether it is Kathryn Johnson, the Atlanta elder who was shot dead in 2006 trying to protect herself when police broke into her home with an incorrect no knock warrant or 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley Jones who was shot in the head by police in Detroit 10 years ago.

Public protest over Breonna Taylor too grew slowly. Now, she is frequently referenced after a list of black male victims as the representation of black female victims of police violence. In the mainstream and black media, they are ‘other’ though three black women activated the Black Lives Matter movement.

However, Black women have been the victims of unspeakable acts of violence from slavery through today. A lot was done in the dark and silenced. Representation of the plurality implicit in the language ‘Black Lives Matter’ language would not detract from attention from the unjust killing and assault of Black men. It isn’t a matter of either/or, but of offering a fuller narrative about racial violence in America.

I went masked with my son to a Black Lives Matter protest in early June. Our sign read 'Mary Turner 1918, Breonna 2020, Atatiana 2018.' We do not need to see Mary Turner, Breonna, Atatiana and the many other Black women victims murdered on video to be outraged enough to immortalize them in public protesting and media. The potentially transformative national awakening about race is undermined without interrogation of the gendered nature of white supremacy and of protest discourse and representation. I hold that sign and make sure my son understands the plurality of black lives matter and why we need to shout as many of their names as possible. Mary Turner, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Kathryn Johnson, Sandra Bland, Aiyana Stanley. . .

+++

Stephane Dunn is a writer, filmmaker, and professor. She earned her MA, MFA, and Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame. Her writings appear in Ms., Vogue.com, CNN.com, and others. She speaks frequently about gender and race particularly in film and popular culture. She is the author of the book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films. Her screenplay Chicago ’66 has been selected as the Finish Line Screenwriting competition’s inaugural Tirota Social Impact winner.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers