How Does A Writer Move You?

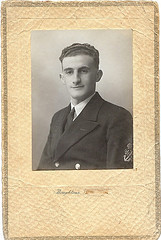

Image by stuartaken via Flickr

Image by stuartaken via FlickrHow does a writer enter the mind, heart and soul of a readerand persuade a mature human being that the fiction purveyed is true enough todeserve and elicit an emotional response? Of course, the question itselfsuggests that every writer does this. But we all know there are writers whosucceed in the market place without ever stirring any deep emotion, relying onthe pace and action of their stories to maintain the interest of the reader.Such writing invariably leaves the thoughtful reader unsettled and unsatisfied,as if they've devoted time and energy to a pursuit that has failed to rewardthem with a fully rounded experience. For me, such writers might persuade me toread one of their novels but I'll never return to waste more time on suchsuperficial entertainment. It serves a purpose, of course, but holds littleappeal for me and many other readers.

If the writing of fiction is about anything, it's surely aboutproviding the reader with a multi-layered experience full of emotional content.As a writer, I want to entertain, of course. But I also want to cause myreaders to laugh in amusement, cry with empathy, gasp in surprise, wail atinjustice, call out in fear, retch with disgust, pause in thought, tremble inanticipation, wince at cruelty, warm with erotic response, scream in terror,applaud at justice, weep at despair andcheer over a deserved outcome.

But how are such responses to be achieved? People are sodifferent, so varied in outlook, experience and education, that it must surelybe impossible to get under their skin in this way? Well, perhaps it isn'tpossible to succeed with every reader on every occasion. But it clearly ispossible to form the desired response in enough of your audience to justify thetime, energy and effort needed to invoke the emotion you're aiming for.

So, how does it work?

I suspect the most important factor is shared experience. Allof us go through the basic events of life; births, deaths, illness, falling inlove and out of it, fearing the unknown, having sex or getting none, admiringsome natural or man-made phenomenon, witnessing a natural catastrophe. We maynot experience all of these events personally, but we will have at least someawareness of them through our family, friends, acquaintances and theever-present media. There is, therefore, some fellow-feeling which can be usedas a platform from which a writer can launch an assault on the reader's senses.

I'll give a couple of personal examples, since these arethings about which I know.

My real father died before I was born and I was raised, fromthe age of four, by the man who later married my widowed mother and calledhimself my father. I was loved, cared for, appreciated and nurtured. I've nocause to feel in any way that I missed out on anything due to my real father'suntimely death.

But. Yes, the 'but' is the crucial aspect here.

But, I always felt that I was incomplete because I'd neverknown my biological father. Because of this, I'm susceptible to certainelements in fiction. One of these is the situation that drives the hugelysuccessful movie, Mama Mia. Theheroine, Sophie, wants to know who she is before she gets married, and sendsinvitations to each of the three men she identifies as her possible father.Now, this motion picture has much in it that should, by the measure of many,not appeal to an average guy. It has been much lauded as a picture for women.That it's also a musical, lends it even more of a feminine appeal in the mindsof many. But, because I absolutely understand, empathise with, Sophie's desireto know about her father, I find the story moving. It touches me in a way thatprobably evades many men. There's a link for me. And that's the point. Irespond to the emotional element that drives the story because I have directpersonal experience of the central emotion of longing to know.

Another incident that never fails to move me is the denouementof The Railway Children . As Bobbiewaits on that railway platform and her father appears through the mist, I'm unableto prevent tears falling. And it matters not that I've seen both recentversions of the film on more occasions than I should. The power of the emotionremains.

Why?

I can identify two entirely separate reasons for this one, Ithink. The first is that I'm a father and have a strong love for my daughter. Ican empathise with the way both a father and a daughter must feel during aperiod of prolonged forced separation. My personal experience lies in thenecessary absence of my girl as she attends university. But there's a secondfactor at play here. I have a deep and enduring concern for justice. Injusticewounds me and always has; perhaps I suffered some unjust event as a child andthis lurks beneath the surface of my consciousness to elevate the quality ofjustice into something of paramount importance to me. I don't know; but it's asgood a reason as any for my concern. In TheRailway Children, of course, the father returns from a spell in prisonserved for a crime he didn't commit. So, the daughter/father reunion isenhanced as an emotional experience for me by the fact that justice isrestored. Hence, I think, my empathy and my inability to prevent the tears.

I use these two examples to demonstrate how powerful a tool emotioncan be for the writer.

Not only the most obvious emotion, that of love betweenadults, as embraced by romantic fiction authors, but all emotion. The readerneeds to be exposed to the emotional spectrum as experienced by the characters,to feel these emotions, not simply to be told that the character feels them.

'Rose felt the sorrow ofloss at the death of her baby.' This tellsthe reader what happened. 'Rose gentledthe tiny crumpled cot blanket in trembling hands, hardly aware of the damptrails she left as she brought it close to her face and inhaled the scent ofthat small perfect person she would never hold again.' This shows the reader her emotions. And,because the author will have built previous experiences into the writing,making the reader empathise with the character of Rose, the reader willexperience the feelings of loss and utter devastation such an event gifts thevictim.

This is one example of how it can be done. So, the writerengages the reader with the character(s), manipulates the reader into arelationship that involves concern and fellow-feeling. Where the thrillerwriter might get away with generic description and superficial emotionalcontent, relying on pace and action to drag the reader through the story, theauthor of almost every other genre must actually become his characters, in thesame way a good actor does, he must feel what the characters feel, in order toconvey the real emotions experienced by the people who act out the tale. Onlythen will the reader experience what the character feels and be moved, amused,shocked, aroused or whatever is appropriate to the situation.

It takes a clevercombination of the right language with a description and presentation of characterthat persuades the reader to care. If the reader really doesn't give a damn whathappens to the character(s), then the author has fallen at the first hurdle andmight as well take up some other activity. It's for this reason that mostserious (serious in the sense of intent rather than style) authors develop theplot through their characters rather than forcing characters into apre-conceived plot.

If you're an author who wants readers to respond to yourwriting rather than skip through the text on a mad dash to the end, you need tobe fully engaged with your characters and to allow them to dictate thedirection of the story. Only in that way will you find the necessary empathy toshare emotional events with them and, thereby, your readers. It's a demandingprocess but one that brings great rewards when handled well.

The picture, by the way, shows my biological father, Ken Burden, about whom I've recently learned a good deal from his surviving sister, my 98 year old Aunt Vera.

Published on January 26, 2012 11:00

No comments have been added yet.