QUESTIONS FROM READERS

I have a silly question. When meditating, I've read one is to be aware, and not much else. However, when thoughts calm down, what is one suppose to be aware of. I check posture. But is the mind suppose to settle on something. Or simply search out--thus disturbing the calm--something to be aware of. I don't know if there is an answer--non-thinking maybe it. But I'm not sure I truly understand non-thinking.

There are no silly questions. Only silly people!

No. I don't mean that really. I don't know why people always want to belittle their own questions. This one's a pretty common one.

The real question is; Does awareness need an object? Or does awareness only appear when we divide subject and object?

In practical terms, when my zazen gets screwy I fix my posture. When it gets screwy again, I fix my posture again.

But there's no real need to be aware of anything specific.

One thing I was wondering if you'd written anything on is the uneasy relationship of zazen and intellectual discourse. This point is difficult for me because I'm sometimes irrepressibly intellectual, and reading Western philosophy has shaped me as much as my practice, but in different ways. Anyway, at times I detect a subtle hostility or contempt for intellectual argument in zen practitioners that I find baffling. For instance, one newcomer recently had mentioned having read up a bit on Zen practice, to which a more experienced practitioner responded, "Oh, no need for those books. Reading just confuses you in my experience." Now, of course she was referring to reading about Zen philosophy, or maybe philosophy in general, but in any case it felt a little knee-jerk. It reminded me of all those times I've been in discussions about X spiritual matter and when I asked--in as humble and sincere a way as I am capable of mustering--for clarification on some point or other, I was met with one of two reactions: A) hostility, because they regarded me as an ill-intentioned provocateur, or B) condescension, like I'm some clueless hyper-educated idiot. Or just frustration, that happens a lot too. And again, most of this stuff is pretty subtle, probably unconscious, but the underlying message less so: Just shut up and accept what is being said. I'm in total agreement that there are limits to how you can talk about, say, the nature of reality or the basis of ethical action, but just because those limits exist doesn't mean that you can't explore the space they contain. Or that, given that teachers use of natural language to explain concepts, you can't prod a little bit in hope of gaining some new perspective. (But yeah, it's a thin line between that and just dickheaded arrogance.) This happens mostly in discussions of the idea of one's "nature/essence," what "energy" is, or "enlightenment." It's all the more esoteric stuff, so not terribly important to my practice. But it does come up every once in a while, and then I feel like people are throwing around terms without a very coherent picture of how they fit together. In other words, I hear a lot of what is flawed logical argument that then retreats behind "the intuitive" when you point out how the logic is whack. To me that is bad dualistic thinking trying to pass as non-dual, where the non-dual answer would seem to call a lot of these concepts deeply into question, including the very idea of an opposition between intuition and intellect.

Oh just shut up and believe what I tell you to!

No! Sometimes this is a knee-jerk response. Sometimes it's a guy trying to be dogmatic about Zen. But often it's neither. You can only take intellectual discussion so far. After that it just becomes pointless. Intellectual discussion is limited by what the brain is able to conceive. The brain thinks it can conceive anything. And in a sense it is limitlessly able to box the universe up in new ways. There is no end to the ways we can frame things for ourselves and for others. But that's all we can do, frame things in different ways.

Dogen was also an intellectual. That's why he wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. He really attempted to frame things for us in the most accurate way possible. But he was also keenly aware that there was no ultimately accurate way of framing reality. So his writing is full of contradictions.

I have trouble keeping my eyes still while doing zazen. I have practiced for several years at this point, and my eyes move around just as much as at the beginning, though my legs have settled into half-lotus, my spine gets in a nice comfortable balance and so on.

Is this part of the posture, keeping my eyes in one spot? That is, should stillness of the eyes be a goal that I should work towards, just like getting into half-lotus posture was for me a few years ago?

I am aware that my eyes moving around is not some random, purely physical, automatic phenomenon. I have at least noticed that moving my eyes is connected to the flow of my thoughts. So another way of phrasing the question is: in your experience, is it best to treat compulsive motions like this as something I need to work on outside of the practice, as I would by stretching my legs, or should I look at it as part of the practice, bring to it the same kind of unattached attention as I would a fly buzzing around the room or the stream of thoughts in my mind?

I used to put a little dot on the wall and stare at that because I had much the same problem. This is kind of an unorthodox answer, though. I don't think Dogen would approve. But he's dead so we can't ask him what he thinks.

I'd say to try to work on this in terms of movement of the eyes. So rather than trying to stop thinking, maybe you can just try to stop your eyes from moving so much. I had some problems with twitching several years ago. I'd get a lot of random muscle twitches. My thumbs would jump up of their own accord and so forth.

I worked on that my waiting to see what happened when a muscle would jump. I didn't try to stop it from happening. Quite the opposite. I wanted it to happen so I could observe how it worked. I found that there was one specific state of mind that I'd go into just before the muscles would twitch. It's impossible for me to describe that state of mind. It was sort of foggy. That's all I can really say.

Anyhow, I found that I was able to avoid lapsing into that state. By avoiding that state of mind, I was able to stop the twitching.

I also found there was no real difference between what we call "voluntary" and what we call "involuntary" movement. That is, there was some aspect of what we usually call "voluntary" movement even in those movements we usually label as "involuntary." I never reached this level, but I would assume this is the kind of thing yogis who can slow down their heart rate or raise their body temperature at will do.

What is a "zen monk"?

I refuse to answer that question on the grounds that it may tend to incriminate me.

But really... what in gosh's name is a zen monk?

For me it's like this. I studied with a Zen teacher for several years. At some point he asked me to go through this weird ceremony called shukke (出家), which means "home leaving." There was also no "or else" element to his request. I could take it or leave it. But he thought it would be a good idea.

I wasn't interested in doing this stupid ceremony. But this was the first time Nishijima Roshi had ever given me any kind of unsolicited advise. He'd answered questions before this. But he'd never told me what he thought I should do. So I figured this must be important.

The ceremony itself was fairly painless. I felt vaguely silly for about 45 minutes and then I was done. After the ceremony I asked Nishijima if I was a monk. He said, "Yes you are a monk."

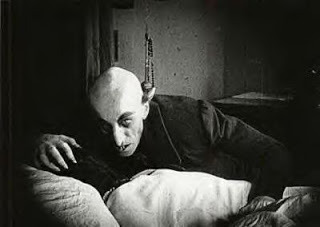

A couple years after that I decided on my own to do the more "official" shukke ceremony through the highly official Soto-shu organization, a gigantic evil religious institution in Japan (but with Nishijima Roshi officiating, since he is a card carrying member of Soto-shu). That ceremony was far more inconvenient and way more embarrassing. I had to shave my head! I looked like Nosferatu for two or three weeks while my hair grew back. It was also really hot the day I did it. And I had to wear these horrible ugly white pajama things and have my photo taken in them. It was pretty awful.

A couple years after that I decided on my own to do the more "official" shukke ceremony through the highly official Soto-shu organization, a gigantic evil religious institution in Japan (but with Nishijima Roshi officiating, since he is a card carrying member of Soto-shu). That ceremony was far more inconvenient and way more embarrassing. I had to shave my head! I looked like Nosferatu for two or three weeks while my hair grew back. It was also really hot the day I did it. And I had to wear these horrible ugly white pajama things and have my photo taken in them. It was pretty awful. But having done that I can now really call myself a Zen monk. It's even written down on a piece of paper somewhere in an office in Japan, filed away with all the other dumbasses who've done that silly ceremony.

But having done that I can now really call myself a Zen monk. It's even written down on a piece of paper somewhere in an office in Japan, filed away with all the other dumbasses who've done that silly ceremony.On the other hand, many people have argued that I am not a monk. Their definitions of what is and is not a monk are different.

Becoming a monk isn't something you can just do on your own. You can't just decide to call yourself as a monk and expect anyone to take you seriously. You have to go through some kind of social ceremony in which someone else declares you a monk. But once that happens, you're a monk.

Of course people still might say you're not a monk. But, to take me as just one example, if someone says I'm not a monk they've also got to say that everyone registered with the Soto-shu of Japan as a monk is also not a monk. And many people do say that. Or else they have to set up their own standards and say that some of those monks are monks while others are not. But these are both iffy positions because you're going up against a really big organization who, though they are evil, have a lot of respect. Which doesn't stop some people from doing so anyhow.

The extent to which you're taken seriously in the big wide world as a monk is determined by the extent to which the organization that gave you the designation is taken seriously in the big wide world. If, for example, Joe's Zen Palour in Ravenna, Ohio calls you a monk that probably won't carry as much weight as the Soto-shu of Japan calling you a monk.

This is the reason I did the Soto-shu ceremony. At the time, I thought it was important to be seen as a legit monk. I now place far less importance on the matter.

Still, I've done the ceremony. Actually these days I'm somewhat embarrassed by that fact. I'm not so sure I'd call it a mistake. But it's not something I would do now if I hadn't done it 12 years ago. For better or worse I am a monk and I'll be a monk for life unless I choose to renounce what I did all those years ago.

As for what it means to be a monk, which is probably your real question... that's a lot harder to say. For me it means I've made a public commitment to zazen practice. That's pretty much it. For others it means following a strict set of regulations. For still others it's a badge of identity.

But these are the only-est Monks who really matter!

Published on January 26, 2012 07:17

No comments have been added yet.

Brad Warner's Blog

- Brad Warner's profile

- 595 followers

Brad Warner isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.