On blindness

It is an undeniable irony of life that, despite his many blessings, man is an ungrateful brute, finding handicaps and obstacles in those things which ought to bless him most. The wealthy man, comfortable in his great house, with his soft furnishings and glowing hearth, is rarely anything but clueless to the plight of the poor and needy. If a man wants for food and raiment, ought he not to work for it? There are jobs enough, surely, our man of wealth and wisdom declares from the chair he has not left all day.

It is an undeniable irony of life that, despite his many blessings, man is an ungrateful brute, finding handicaps and obstacles in those things which ought to bless him most. The wealthy man, comfortable in his great house, with his soft furnishings and glowing hearth, is rarely anything but clueless to the plight of the poor and needy. If a man wants for food and raiment, ought he not to work for it? There are jobs enough, surely, our man of wealth and wisdom declares from the chair he has not left all day.

Even modern conveniences, when they have outlived their novelty, become a source of irritation when they fail us in their obligations. We have employed them, paid good money for them, ought they not to work as they were designed to do?

The weather, as mundane a thing as can be imagined, yet manages to vex our lives as few other things can. The sun that makes it possible to grow our vegetable gardens and to take our vacations to seaside towns, is often too glaring or too warm. Conversely, the rain that waters the crops, that fills the rivers and streams, ruins our plans and dampens our moods.

Our five senses, likewise, are blessings of which we are rarely mindful, save when we cannot use them to their best advantage. We curse our noses for the colds they catch, our hands for the injuries they suffer, our ears for the sounds that annoy us. The seeing man is often blinded to the subtleties of his environment by the obvious. He takes what he sees as truth and rejects what might lay beneath the surface. A beautiful house is more desirable than a humble one, however inconvenient it may be. A beautiful woman, likewise, far more suitable than she who, though clever and resourceful, has less to be proud of in her appearance.

Those five senses (though some may argue six), while so essential to our lives, are things we too often take for granted. Is it possible that one, being deprived of a part of his natural senses, might appreciate them all the more? Might he have a sweeter understanding of life and its hidden meanings?

Perhaps.

Perhaps not.

* * *

In a large suite of rooms in a sprawling country house, sat such a man as we might put these questions to. At the moment we join him we see that he is annoyed to distraction by the apparent lack of urgency conveyed by the firm pulling of the chord to the bells that are attached at its furthest end. In short, his servants are too slow. But this is only a part (though admittedly the greater part) of his anxieties. Other considerations circumstantially have added to them, for the weather, too hot yesterday, is dreary and damp today. A strange dog has found its way onto the property and will not leave off barking. His ears are ringing and his head has begun to ache. His tea, now cold, has too much lemon. And on top of all this, he suspects he is coming down with a cold.

As to his sight, he cannot complain. That is, he has no new complaint to speak of. Arthur Tremonton was born, to his mother's shame and his father's embarrassment, blind.

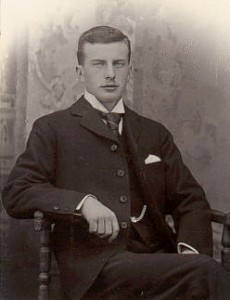

By his staff, Arthur might have been described—were you to ask them, and assuming they were inclined to oblige—as a man of better than average looks. His hair was fair and grew thick upon his head. His eyes bore no evidence of his malady save in their unusual paleness, a liquid blue that appeared almost white. He was tall, lithe and elegant, well dressed, well groomed and immaculate in speech if not entirely in manner. And, perhaps most significantly of all, he was well educated, which was an extraordinary thing considering he had never had a single day of school. No, he had lived his life in this house, confined, almost exclusively (at first by the dictates of his parents, now dead, and then by habit) to an upper suite of rooms. He had been provided with tutors, naturally, but it was not until he had inherited his father's library, and the vast collection of books within it, that his education ventured into anything nearing higher learning. The deficiencies consequent of an education directed by a too protective mother and an emotionally absent father were more than made up for in the years that followed their passing.

Of course it was not the library alone Arthur had inherited, but the house, as well as its large park, its ample staff, and even, to his great fortune, his father's aged valet. Blind as he was, Arthur could not read, but he could hear, and he could remember, and he could understand like few others. It is true what they say, a deficiency in one sense will be made up for by those that remain. He had an almost supernatural gift of recollection, a keen comprehension of concepts, histories, theories and philosophies he could only experience in his mind. It was certainly a fortunate thing that Arthur had been born to money and position, for, at the age of seven and twenty, he could apply himself to no more practical occupation than that of a perpetual scholar. He had no skills to speak of that were not of the cerebral persuasion. Had he been born a poor man, a mill worker, or a printer, a farmer, perhaps, he would have been at the mercy of an unforgiving world. What hardships he would have had to endure! He could not imagine it. But then he never tried. A man's hardships were his own business. Arthur had his own trials, and they were quite enough.

Where was Mrs. Pritchet with his tea! He rang the bell once more.

Some, he knew, made themselves burdensome, and with far less reason than Arthur possessed. And yet hadn't he made something of his life?

Again, he applied his hand to the bell cord. Harder this time. Surely it was working well enough.

He needed no one. (Which was perhaps a good thing as he had no friends.) And he had money enough to keep him quite snug and secure for the remainder of his life.

If only the staff would mind their duties! He pulled the cord again.

He would not make a nuisance of himself for the world! Such were better off dead. He would bother no one by his infirmity. So why was it that the charity ladies must keep coming? All others had learned by now not to bother. Their efforts were wasted to extract money, or to plumb the depths of his soul, or his intellect. He was not a man to entertain, or to keep up pointless conversation.

Was he lonely? Well, yes. Of course he was. But he valued his privacy and solitude more than he did company, who could rarely keep up conversation, were invariably stupider than he and could only talk about the things they saw and the places they went, as if they meant to brag of the talents they possessed and of which he had been born deficient. It was, in truth, nothing more than an insult to his impairment. He was blind! Was he ever going to cease to be blind? No! Would he ever be able to embark upon such adventures on his own? Of course not! So what use was there in discussing them? Try as a man might, Arthur could not be made to understand what a banana tree looked like, or an elephant or the ocean. The phrases 'large as a house', 'fast as a horse', 'grey as the sea'… these meant nothing to him. One cannot comprehend the size and shape of a buffalo if one has not seen it for oneself. One cannot describe the shades of the dusk-lit sky if one has never seen colour or shade or even vast and open space. It is impossible. And it is insulting! And he did not cower in telling them so.

Wisely, and mercifully, these visitors had ceased over time to come at all. All but the wretched, annoying, supercilious young women of the Ladies' Charitable Aid Society! They would come this very afternoon, despite a grumbling sky and the rain that tapped at the windows. They would come. They always came when he wished most to be left alone. Just see if they didn't!

***Blind is a soon to be published novelette. More info will be forthcoming. Stay tuned.***