An Adventure of Her Own

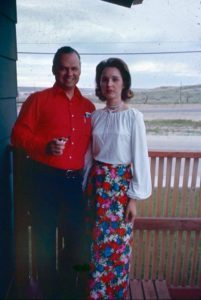

My mom, Eleanor, died Friday, June 5, 2020. I hope she’d say she lived a life full of adventure.

I’m the seventh of eight children. There were always enough of us to field a baseball team, or play a rollicking game of Tripoli and Michigan Rummy, or to stage a bike race, or to tell round-robin stories at dinnertime. But someone needed to corral us, feed us, clothe us, bathe us, and make sure we weren’t completely feral.

That someone was Mom.

When they got married, Mom was 18 and Dad was 19. By the time she was 23, she had five kids. I was born when she was 30.

This math always floors me. I have three kids, my first when I was 26 and my last when I was 31. My husband and I joked that when we had our third, we had to go from man-to-man to zone defense. But what in the world did my parents have to do?

We were never wealthy, and some lean years were very lean indeed. But Mom always made a little bit seem like a lot, certainly more than enough, and always plenty. I learned that from her. I add a bit of water to a can of tomato sauce and swirl it to remove every bit. I sewed my own clothes. I run cold water when I turn on the disposal because when I was a kid, she taught me that was how it had to be done.

This last bit may be dubious information, however.

At the time I accepted her instruction with unquestioning gravity, but long after I was an adult I asked her why was it so important to use cold water with the disposal.

“Beats me,” she said. “Who told you that?”

“You did.”

“Hm. Wonder why.”

I was also a grown woman when I realized Mom must have had other hopes and dreams besides raising eight [perfectly remarkable and hardly feral] kids.

And by “realized,” I actually mean “got gobsmacked.”

I’ve blogged about this before, so indulge me if you’ve heard this story.

I got mad at my three children one day when they were youngish and terrible. I needed more than a time-out so I ran away. Only as far as the local library in our little Colorado town, but it was far enough. Far enough for me; too far for them.

I don’t think my kids were particularly scared, but they called my mother in California to tattle on me.

That evening, Mom called. When I told her the story of the behavioral chaos of my naughty children, expecting her to scold me, she laughed. “I’ve done the same thing,” she said. “Many times.”

I was immediately calmed and exonerated.

I shared that story on my blog ten or so years ago, adding this ….

I was reminded of this story today because I sat on the deck reading DEAR MRS LINDBERGH by Kathleen Hughes. It was a book I had given my mother as a gift several months earlier. She’s becoming more and more housebound caring for her declining husband. She has very few needs, so books, I’ve decided, are an excellent gift.

She lives in an apartment without much shelf space, though, so she carefully writes the name of the gift giver on a sticky note and returns the books when she’s finished. Often, she’ll include a note about how she enjoyed it—or didn’t.

Sometimes I give her books I’ve read that I know she’ll like. Other times I browse and find books I think she’ll like.

Such was the case with DEAR MRS LINDBERGH. I hadn’t read it, didn’t know anything about it. But I know Mom likes historical fiction, which this wasn’t, really, but it had that feel to it.

When I got to the end, I found a note from my mom tucked into it. In her precise cursive she told me she liked this one. She added, “On a very small scale I can relate to Ruth’s desire to fly away for an adventure of her own.”

Reading her note literally took my breath away.

My mother had eight children. I’m number seven. I was an adult before I ever knew—or thought to ask—if she had dreams for her life that didn’t involve a swarm of kids. She was a young teenager during World War II and the nurses captivated her imagination. But then she turned 18, got married, and immediately started having children. She and my dad never had any money. Nursing school was out of the question.

“On a very small scale I can relate to Ruth’s desire to fly away for an adventure of her own.”

I know Mom would say she’s had a perfectly fine life. But my heart has several tiny Mom-shaped cracks in it today.

I contrast my life with hers all the time. From the beginning, my husband and I had more money than she and my dad did. First, both of us had college degrees and we both had well-paying jobs upon graduation. We were able to buy a house in southern California before our first child was born. We had two cars and a washer and dryer, something my parents didn’t have for many, many years.

They’d cobbled together their American dream, gaining and losing ground periodically, but mostly making progress.

But when Mom was about fifty, her marriage to my dad suddenly crumbled. I didn’t appreciate how scary that must have been until I got to be about that age.

Here she was, fifty years old, only been in the labor pool for ten years or so in a handful of non-career-type jobs and boom—on her own. I was in college at the time and my younger sister was fifteen-ish. There was more than a little drama during that chaotic time, but because she was a practical woman, she rallied and soon enough took charge of herself again, with renewed determination.

It wasn’t long before she met someone and remarried, creating another long-term happy relationship.

And let me tell you, aside for its length and general happiness, this relationship was nothing like her previous one. First, this man was a tea-drinking, soccer-watching, Royal Air Force-pensioned British jazz musician, a far cry from my conservative insurance executive dad.

Second, they sold all their belongings, bought a big ‘ol RV, and traveled around the country attending jazz festivals.

Mom never became a nurse, or went to college. But in her 60s, she climbed into the driver’s seat of that monstrous vehicle and maneuvered it all over creation. She got on stage playing her fully-decked-out washboard in front of festival crowds, and found herself on the cover of the Wall Street Journal for it. She traveled to Europe.

She’d never have done any of that with my dad.

1994 Sacramento Jazz Festival

As I watched her dying in her hospital bed the other day, with her labored breathing and gaunt features, I wondered what she was thinking. Was she thinking about us? Was she praying? Was she remembering her life? I hope so. I hope she felt she’d finally had an adventure of her own.

When I had to leave, I kissed her on the forehead and thanked her for being a great mom. I also apologized for not being a great daughter. She roused herself from the morphine cloud and grinned at me. “You were fine. I love you.”

Later, relaying this to my husband, I laugh-cried because her subtext struck me funny. “Yeah, you were a perfectly adequate daughter. Not perfect, not terrible. Average. Solid C+. You could have applied yourself better, done more chores without being asked, visited more. And would it have killed you to bring me more wine?”

Mom with all her daughters

My sister Barbara wrote this in a letter to Mom recently and I thought it was so touching and exactly right.

“When I was a girl, my friend Leslie’s mother threw a birthday party every year for her, right before Christmas, and gave all the kids their own ornament with their name handwritten in glitter. I still have one and I hang it up every year on my tree. It reminds me of my childhood. I know someday it will break and every year when I get out the bins of decorations, I’m surprised to find it is still intact. But even if it were to dissolve into a million tiny pieces of green glittery dust, I’ll remember it, and my childhood.

And when you’re gone, and you’ve dissolved into a million glittery bits, I’ll remember you. When I put all the ingredients out on the counter before I mix up the recipe, when I do my chores before I go out to play, when I laugh helplessly over some nonsense, when I treat my children as equals, when I craft something beautiful or useful, when I notice lyrics that touch my heart, I’ll remember you.”

So, godspeed, Mom. Thanks for everything. I hope you enjoyed your eighty-eight year adventure.