I have long been interested in how death is mediated online....

I have long been interested in how death is mediated online. Occasional stories crop up about receiving Facebook ‘Year in Reviews’ with the images of dead friends, or more challenging tales about trying to access digital data from deceased loved ones. Quite simply the complexities of our digital afterlives are poorly understood. Labyrinths of information, layers of passwords, and a host of legal contradictions regarding ownership, jurisdiction, and user agreements. I have previously toyed with this in the way my kids created an online pet cemetery in Minecraft.

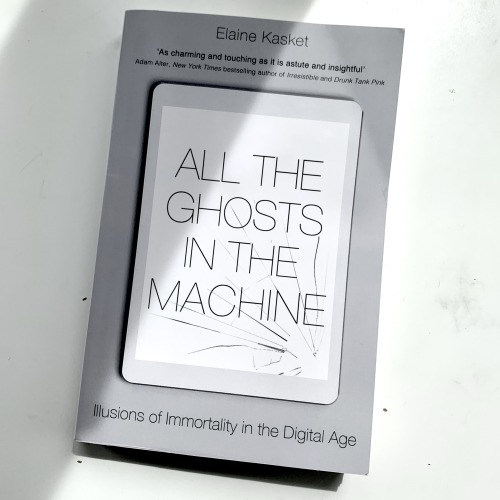

One thing is for sure, even the most disinterested and lightest of users of digital technology will have a sizeable digital footprint. This digital footprint is something that people may well want to exercise some form of control over. Yet very few are prepared to do so. This is the context in which Elaine Kasket writes, leading the reader to consider a host of issues that are problematic, emotionally compelling, and unavoidable.

Consider the following issues, who will inherit your iTunes library once you die? It might be simple to pass on physical books, but who has the right to your digital texts? How would you manage the social media feeds of a recently deceased spouse, or child? What privacy would the dead expect, and what level of control would others demand? This all gets more complex when we consider that the information (or data) that is posted online tends to have mixed ownership. Photos of friends might well relate ownership not just to who is in them, but who took the photo. Private messages are also a legacy of communication between at least two people and thus cannot simply be rendered to a third party after death. Or can they?

Much of this book deals with a variety of interesting case studies that introduce us to the problems many have faced in dealing with a digital legacy. As the book progresses we turn more towards the provisions, strategies, and businesses that are emerging to tackle digital life beyond death, or ‘death tech’. Some of this tackles themes from pop-culture films and television like the Black Mirror episode ‘Be Right Back’.

The book closes with ten helpful suggestions regarding the management of your own digital legacy. Each of these points is fleshed out earlier in the text in considerable detail, but are turned toward the reader in conclusion. One of Kasket’s messages is to think seriously about what you might want preserved. What digital content represents you, what content would you like your legacy to be?

All this made me think of my Tumblr blog. This is perhaps the greatest resource of ideas and interests that I place online. Less personal than my old Facebook profile, which I eventually deleted, but far more a product of my own creativity than much of my other social media. Even Instagram has become mediated more by who follows me than what I really want to post… My academic work also orients to a particular perspective and tone, so while my publications are a legacy they are a peer reviewed legacy. Tumblr is however a voice that I simply don’t get to use in other social media, even if I refrain from posting some of the quirkier side of my interests and personality. Even more curious is the fact that just a year ago Tumblr was pronounced dead after the platform scrubbed all the porn off. Yet, many have stubbornly persisted with their blogs and perhaps Tumblr is due for a renaissance. However powerful and monolithic Facebook and Twitter may be, there are no guarantees they or any other social media will stick around. They are built to be archives. Indeed Tumblr provides a curious intersection with digital life after death. Blogs live on, and the dead are also easily able to post in their absence with the queue function. Even more permanent, and likely to outlive an electromagnetic pulse, is the printed Tumblr, blog, or social media feed. Years ago a friend signed up to a now defunct service which would compile all your Tumblr posts and print them as a book. There are now other such services.

So we are in a rather profound moment. At one level I am likely to back-up hardcopies of letters and old photos by scanning them, but now I am also considering making hard copies of some of my favourite digital creations. This, as Kasket adeptly shows us, is just the tip of the iceberg.