#BlackEphemera: Remembering the Sensual Soul of Jon Lucien

#BlackEphemera: Remembering the Sensual Soul of Jon Lucienby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“I would say that my sound is a romantic sound. It’s water. It’s ocean. It’s tranquility.”—Jon Lucien

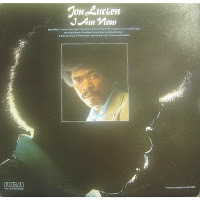

That Jon Lucien’s name is rarely evoked in casual conversation about Jazz and Soul vocalists of the past two generations is perhaps fitting for an artist who was often cast as an outsider. Born in British Virgin Islands in 1942, wasn’t just his Caribbean accent that marked Lucien (born Lucien Harrigan) as different when he first emerged in 1970 with his debut recording I Am Now, but his embodiment of something else—that something else that few, including his record labels, could ever quite wrap their heads around.

If so much of the Soul music of the early 1970s yearned for the trinkets of a newly formed freedom—including the freedoms derived from uninhibited sexual passion—then Jon Lucien’s music, his rich baritone and his cosmopolitan swagger were evidence of an always, already freedom, that the mainstream was never quite ready for.

If so much of the Soul music of the early 1970s yearned for the trinkets of a newly formed freedom—including the freedoms derived from uninhibited sexual passion—then Jon Lucien’s music, his rich baritone and his cosmopolitan swagger were evidence of an always, already freedom, that the mainstream was never quite ready for.It is all too easy to compare Jon Lucien to Barry White, Teddy Pendergrass and much later Luther Vandross (the sheer heft of their vocals would have it no other way), but in reality Lucien’s peers were song stylists like Johnny Hartman and Jimmy Scott—both largely forgotten, even as Scott (and his natural falsetto) garnered new audiences up until his death in 2014 and Hartman remains the only vocalist to have collaborated with John Coltrane. As Lucien recalled in an interview, his label at the time, “was attempting to package me as a sort of ‘Black Sinatra’.”

Neither Scott or Hartman – or Sinatra for that matter – possessed the one thing that made Lucien so unique; Jon Lucien conjured sex in a way that was only comparable in the era to the on-screen smolder of Calvin Lockhart, who like his Caribbean contemporary, never quite found the vehicles to support his considerable talents. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was difficult for male Caribbean artists to exist beyond the huge shadows of Sir Sidney and King Harry; Lucien and Lockhart, I would argue, suffered accordingly. Ironically Lucien first came to the states in the 1960s playing bass in the Catskills behind a trio that once performed as part of the Harry Belafonte Folk Singers.

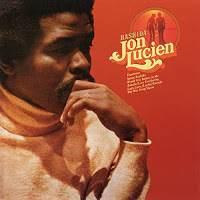

Nevertheless Lucien’s second recording, Rashida (1973), with its lush arrangements, unbridled percussive energies and Lucien’s vocals in fine form, ranks as one of the great “Soul” albums from the period. Whereas his debut included rank-in-file covers like “The Shadow of Your Smile,” “Love for Sale,” and Stevie Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour,” Rashida was written and arranged by Lucien. A few of those Lucien originals like “Lady Love” and “Esperanza” – which featured Lucien accompanying himself on guitar over his layered vocals – became classics in their own right, but none more than the title track.

“Gentle as the sigh of a morning breeze/Rashida calls my name” is how Lucien opens “Rashida” as he proceeds to tell a story about a love lost. The song’s tension comes from “Rashida’s” return and Lucien’s lament, that desire, was perhaps more palpable than regret, singing “when I needed you/you ran away…now your body’s yearning for my touch.” When asked about the song’s popularity, Lucien told Essence magazine some years after “Rashida’s” release, “I don’t know. I guess at the time that song came out there was no music like that around. Back then, Black men were not singing songs with those kind of lyrics.” The song, along with “Lady Love,” became Quiet Storm favorites.

“Gentle as the sigh of a morning breeze/Rashida calls my name” is how Lucien opens “Rashida” as he proceeds to tell a story about a love lost. The song’s tension comes from “Rashida’s” return and Lucien’s lament, that desire, was perhaps more palpable than regret, singing “when I needed you/you ran away…now your body’s yearning for my touch.” When asked about the song’s popularity, Lucien told Essence magazine some years after “Rashida’s” release, “I don’t know. I guess at the time that song came out there was no music like that around. Back then, Black men were not singing songs with those kind of lyrics.” The song, along with “Lady Love,” became Quiet Storm favorites. Rashida earned Lucien two Grammy Award nominations; the title track and “Lady Love” were both nominated for Best Vocal Arrangements, in a category that included Diana Ross’s “Touch Me in the Morning” and Paul McCartney & Wings’ “Live and Let Die”, which won the Grammy. The fact that Lucien was nominated twice in an arguably obscure category, highlights the challenges that he and his record label faced in trying to market him. As Lucien told Richard Harrington, “There was a lack of vision, especially when we did the Rashida album…everybody was saying, ‘what do we call this music?’” Such questions kept RCA from giving Lucien’s recordings full promotional support, particularly in an era when many labels were still getting a handle on their nascent Black music divisions.

If records didn’t sound like Al Green, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, The O’Jays or Aretha Franklin, many labels didn’t believe there was an audience for it. Indeed Lucien began his career recording a series of singles like “The Pied Piper” for Capitol Records in 1969 and “What A Difference Love Makes” for Columbia in 1967. The songs were credible Soul-clappers, but in retrospect, they lack any of the musical distinctiveness that Lucien became known for.

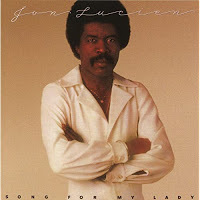

The challenge of Lucien’s music was borne out in the commercial failure of his third RCA album Mind’s Eye (1974), an album that is arguably more audacious than Rashida. Released the same year as Quincy Jones’ Body Heat – the album that helped establish what we now refer to as Smooth Jazz – Mind’s Eye simply didn’t find an audience. Lucien expected better fortunes with a move to CBS records, arriving the same year of Bill Withers’, who Lucien would later cover with “Hello Like Before”. His CBS debut Song for My Lady, might be Lucien’s most accomplished album, featuring originals like “Creole Lady” and the “Rashida”-like title track, and a cover of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Dindi”, which Lucien also recorded on his RCA debut. Two of the most ambitious songs on the album were “Motherland”, which was written by Berhnard Igner, who is most well known for producing Marlena Shaw’s Who is This Bitch, Anyway? And for writing and singing “Everything Must Change” from the aforementioned Body Heat by Quincy Jones. The other was a reinterpretation of Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage”, featuring lyrics from Hancock’s sister Jean Carole Hancock.

Lucien continued to record quality music on his follow-up Premonition which included a lovely, if over-produced, remake of Bill Withers’ “Hello Like Before” and stellar cover of Johnny Mercer’s “Laura,” which did little to enhance Lucien’s sales. With Disco and Funk dominating Black radio in the late 1970s, Lucien retreated into a world of depression and cocaine addiction. Reflecting on those years, Lucien told Essence in 1991 “The truth is, I was scared of the business. By the time I made my fifth album I began to realize that that I was doing all the music and coming up with all the ideas…I should’ve been getting producer credit. I just thought, I’ve gotta get out of here.” Lucien’s depression was exacerbated by the drowning death of his infant daughter.

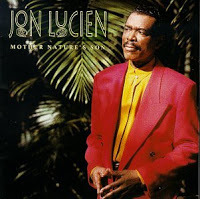

Lucien continued to record quality music on his follow-up Premonition which included a lovely, if over-produced, remake of Bill Withers’ “Hello Like Before” and stellar cover of Johnny Mercer’s “Laura,” which did little to enhance Lucien’s sales. With Disco and Funk dominating Black radio in the late 1970s, Lucien retreated into a world of depression and cocaine addiction. Reflecting on those years, Lucien told Essence in 1991 “The truth is, I was scared of the business. By the time I made my fifth album I began to realize that that I was doing all the music and coming up with all the ideas…I should’ve been getting producer credit. I just thought, I’ve gotta get out of here.” Lucien’s depression was exacerbated by the drowning death of his infant daughter. Save a one-off album on the independent Zemajo label, it would be nearly a decade before Lucien released another studio recording in the United States as he healed emotionally and physically back in his birthland. Ironically it was Lucien’s popularity of radio formats that didn’t exist when Rashida was released, Smooth Jazz and The Quiet Storm, that brought him back into favor with record labels. Lucien recorded two albums, Listen Love (1991) and Mother Nature’s Son (1993) for the Mercury Label.

If there was a classic Lucien sound, Listen Love captured it, albeit updated for contemporary audiences. The album was anchored by “You Take My Breath Away”, which featured his wife Delesa Lucien on vocals, the breezy “You’re Sensational”, and the lead single “Sweet Control”, which was promoted with Lucien’s first music video. Mother Nature’s Son was more of a mixed-bag, the label trying too hard perhaps to have Lucien ride the Smooth Jazz wave, but there were standouts like the closing duet “I’ll Be Loving You” between Lucien and Melba Moore, and the Van Heusen & Burke, standard “But Beautiful”. Additionally Lucien joined Nnenna Freelon on a beautiful rendition of The Shirelles’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” on her album Listen (1994).

Lucien was in the midst of a fairly successful return (at least by Smooth Jazz standards) when he was forced to bury another daughter. Dalila, Lucien’s 17-year-old daughter, was a passenger on the ill-fated TWA 800, which crashed in July of 1996. Saxophonist Wayne Shorter’s wife also perished in the crash; Shorter was Lucien’s brother-in-law from an earlier marriage. Like so many of his fans, Lucien found comfort in his music, recording much of his 1997 recording Endless Love (Shanachie) while he was in mourning. In the liner notes to the recording, which was dedicated to Dalila and all who perished on TWA 800, Lucien wrote “My infinite love, Dalila: I have always been your father and will continue to be, throughout all our lifetimes, on earth and in forever after. Visit me soon, my darling. You are my music.” And indeed in the last decade of his life, Lucien recorded some of the most personal music of his career, paying tribute to that career with By Request (Shanachie), where he offered interpretations of his own classics, including a third-go-round with “Dindi”–a rendition that marked the storms he had weathered.

Lucien was in the midst of a fairly successful return (at least by Smooth Jazz standards) when he was forced to bury another daughter. Dalila, Lucien’s 17-year-old daughter, was a passenger on the ill-fated TWA 800, which crashed in July of 1996. Saxophonist Wayne Shorter’s wife also perished in the crash; Shorter was Lucien’s brother-in-law from an earlier marriage. Like so many of his fans, Lucien found comfort in his music, recording much of his 1997 recording Endless Love (Shanachie) while he was in mourning. In the liner notes to the recording, which was dedicated to Dalila and all who perished on TWA 800, Lucien wrote “My infinite love, Dalila: I have always been your father and will continue to be, throughout all our lifetimes, on earth and in forever after. Visit me soon, my darling. You are my music.” And indeed in the last decade of his life, Lucien recorded some of the most personal music of his career, paying tribute to that career with By Request (Shanachie), where he offered interpretations of his own classics, including a third-go-round with “Dindi”–a rendition that marked the storms he had weathered.As the twenty-first century began, Lucien broke from the dictates of the mainstream labels and founded his own label, Sugar Apple, releasing three studio albums between 2002 and 2008. Lucien spent much of his later years battling kidney disease—he received a transplant a few years earlier—and ultimately it was complications from that disease that called him home. Lucien bravely told Richard Harrington back in 2003 that “I’m not going anywhere until the Lord wants me.” And apparently on August 18, 2007, the Lord had need for a rich Caribbean baritone, but as he told his own Dalila, the spirit of Jon Lucien will live on in his song.

Published on May 13, 2020 17:27

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.