"Scheherazade" — A Guest Post from Art Holcomb

by Art Holcomb

Two pieces of paper hang above my desk.

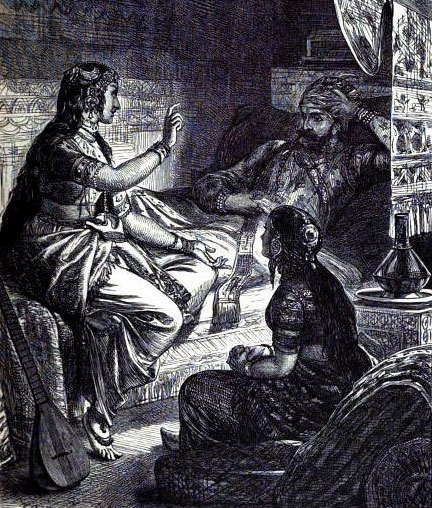

One is a quote (more about that next time) and the other is the picture below. It is from One Thousand and One Arabian Nights.

As the tale goes, the Persian King Shahryar would marry a new virgin each night only to slay them the following day. He had gone through a thousand virgins before he got around to Scheherazade, the daughter of the King's vizier; a woman who was witty, wise and – most importantly – well-read.

So as to avoid being slain, Scheherazade spun for the king a fabulous story but stopped in the middle. So enthralled by the story was the king that he broke his rule for the first time and spared her life for a day so she might finish the story the next night.

But the following night, Scheherazade finished that story and then started another – only to stop halfway through once more as dawn approached.

The King spared her again.

This pattern continued for a thousand and one nights. By the time Scheherazade ran out of stories, the king had fallen deeply in love with her.

I look at that picture and think about Scheherazade each time I work on a script. She was THE consummate storyteller and understood that how you tell the tale is at least as important as the tale itself. I try to always edit my own work with the image of a swordsman's blade waiting for me if I should ever lose my readers' or viewers' interest.

If the greatest duty of the writer is to the truth, then the greatest obligation has to be to not bore his audience. And since the majority of my work is scriptwriting – with its tight time limits and page counts – I ask the same question of all my efforts:

Is it dramatic enough?

I have long subscribed to the famed screenwriter and playwright David Mamet's definition of the dramatic scene:

"The quest of the Hero to overcome whatever ever obstacles there are that prevent him from achieving his goal. Each scene must culminate with the Hero finding him/herself either thwarted in his attempt or educated that another way to achieve his goal exists."

This is the crucible in which all scenes must be tested. Pass this test and survive or fail the test and be cut out.

The three filters Mamet uses for every scene are:

Who wants what?

What happens if s/he doesn't get it?

What HAS to happen next?

Answer these three questions truthfully and you'll be able to tell very quickly whether your scene works as drama or not.

For me, I work from outline, not long but broke into beats. And, invariably, someplace between the outline and first draft sprout all manner of talking head scenes, extraneous material and false starts. It's natural and I let it happen because sometimes I learn things about the characters here that I didn't know before.

But they never survive the later drafts because here is where I have to be ruthless. Any scene where two people are talking about a third has to go unless by taking it out I lose my audience's focus. Applying the filters above, I know that each scene builds – unfold – upon the last. Each character must have a pressing need that impels him from the last scene into this one and then from this scene into the next. There must be a real reason for him/her to show up each time. If there isn't, the scene will be boring and that violates my First Rule.

From Mamet again:

"This need (compelling reason) is why they came. It is what the scene is all about. His/her inability to get their need met will lead, at the end of the scene, to FAILURE – this is how you know the scene is over. This failure will then, of necessity, propel us all into the next scene."

. . . and so on until the final resolution.

These attempts and failures, taken together, constitute your plot. Note here this is your plot, NOT your story.

Think of it this way: your job here is to make the audience/reader NEED TO know what happens next.

Questions:

Ask yourself these questions about your current piece:

How much of the time are you TELLING the readers what's happening versus SHOWING them through your character's actions?

Be honest with yourself: are there passages in your current work that can't hold your own attention? If so, why should they then hold your readers'?

Do your scenes flow necessarily from one to another? Look at the juncture at the end of any given scene. Is this where your characters should be heading? Are you still interested in seeing what they do next?

Practice Exercises:

Choose a scene you're having trouble with:

If it's dialogue heavy, try rewriting the scene without dialogue – just description and action. See how much of the content you can give non-verbally.

Try staging the scene in a different location of the story. See if the location adds better continuity and drama.

If it still doesn't work, consider eliminating the scene altogether. Can you move the main element of the scene to another that works better?

Next time: Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock . . .

Art Holcomb is a massively credible creator of illustrated novels (comic books), and is a screenwriter, workshop instructor and, lucky for us, a regular guest blogger here on Storyfix. He will be lecturing this spring at the USC School for Film and Video, as well as doing a workshop at the Willamette Writers Conference in August 2012.

"Scheherazade" — A Guest Post from Art Holcomb is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com