How We Got into This Financial Mess

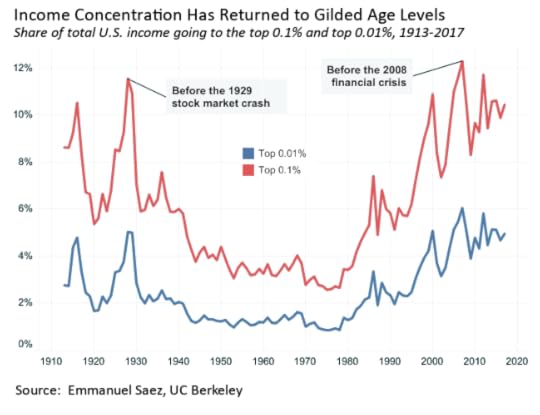

The ‘markets know best’ theory led to the financial deregulation of the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s which put finance back to the casino days of the 20’s and justified tax cuts for the rich. It created the financial inequality that we see around us and, like all movements, was based around a theory: Neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism has also been also called Reaganomics and is in fact trickle-down theory. Its premise is pretty straightforward, and although it is a proven failure, it is continuously resurrected. Basically, the theory is that the market knows best and will self-correct. It claims that there should be minimal regulation, minimal tax and minimal interference from the government, so that the markets can do what’s best. Financial crashes are justified as just self-correction and government/taxpayer bailouts are too. Hmm, I don’t think bailouts are supposed to be part of neoliberalism, the contrary in fact.

Neoliberalism was used to justify financial deregulation and tax cuts. A 20th century conservative economist, named Art Laffer, believed in a magical tax rate at which he claimed people would stop working if they were taxed too much. And if you cut taxes for the rich, they would work longer, harder and better, and the fruits of their endeavours would trickle down to everyone else. Thing is, today most people work jobs that require them to be there, regardless of tax rate, and if they don’t work, they won’t receive any pay at all. As far as billionaires go, I can’t see how billionaires are able to work more hours than already exist in a day, and they certainly aren’t billions of times more productive than the rest of us.

Laffer sold the theory to Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney in a bar in 1974. This was the foundation of Reaganomics. Incidentally, President Trump has just awarded Laffer the Presidential Medal of Freedom. …Although, that might have been because Laffer wrote a book called Trumponomics…

That’s what Trump’s tax cuts are: trickle down. These cuts helped create the biggest one-month deficit in US history at $234 billion. Trump, who pledged to eliminate the US deferral debt in eight years, has actually increased it by more than $2 trillion in just two years, when the US economy is supposedly healthy.

Neoliberalism didn’t work in the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s and 2000’s and it’s certainly not working now.

Even after the Great Recession of 2008, nothing has changed. The financiers kept ‘their’ money and went back to business as usual. Even the $139 billion in fines imposed on banks between 2012 and 2014 had no impact. In fact, the derivatives market was 20% bigger in 2013 than in 2007 before the crash. The fines were chump change to the financiers.

Financial Deregulation

As well as tax cuts, four important things happened on the financial deregulation front. Well, more than four of course, but for the purposes of what I’m writing, let’s look at four.

Things changed in the 70’s and 80’s. But, first here’s a quick explanation of some investment banking speak as everyone should be clear about two terms that are used frequently in banking: ‘going long’ and ‘going short’.

Going long is fairly straightforward. You like something, like a share or bond, so you buy it and hold onto it. You hope it will rise in value and/or provide an income stream. You are making an investment in the future.

Going short is the opposite. It is selling a stock or bond you don’t own with the expectation that the price will drop. If you plan on doing this for longer than a few hours you will need to find someone to borrow the shares or bonds from, to give to the person you sold them to.

As an example, you might think that the UK government is going to raise interest rates. If this were to happen, then government bonds would drop in price – remember the wings of an airplane? So, you decide to sell 100 bonds at £100 hoping those bonds will be worth less in the future. You sell the bonds, but you need to deliver (give) them to the buyer that you sold them to. What you do is ‘borrow’ the bonds from someone else. Say a pension fund. The pension fund loans you the 100 bonds for a month and you pay them a fee for this, so they make a little extra money on those bonds. By the end of the month, if things go as you planned, the bond price has dropped to £90, so you actually finally buy the 100 bonds in the market (cover your short) and make £10, minus what you paid the pension fund to lend them to you.

The four changes:

The first is that investors were allowed to sell shares they didn’t own (to go ‘short’). Previously, only market makers could do this, in order to maintain a market in a share, and would close the ‘short’ position out as soon as possible. This is a big part of what happened with ‘Big Bang’ (1986) in the UK: deregulation of the financial markets. Again, lots more went on, but one of the far-reaching changes was being able to ‘short’ a share if you felt it would go down in price. Investment groups calling themselves hedge funds were born. Their speciality was ‘betting’ against companies, not investing in companies.

Hedging used to mean removing uncertainty by using futures and options (hence the name hedge funds), where ‘hedge’ implies minimising risk. It used to be about selling next month’s corn harvest at a price agreed upon today (selling something you don’t have yet) or buying next month’s oil at a price agreed today. But hedge funds aren’t hedging anything, they are simply betting by selling something they don’t have. And yes, even they call it ‘betting’.

The second was the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in the US. This was introduced in 1933 after the stock market crashes of the 20’/30’s. It separated retail banking from investment banking. By repealing the law, retail banks were allowed to use their balance sheets to ‘invest’ in or bet on the markets. And, they didn’t just bet $1 for every $1 dollar they had. They ‘geared’ up and invested $10 or more for every $1 they had on their balance sheets, the balance sheets of the retail banks being all the money on deposit with the bank. So, many retail banks went into investment banking because shareholders wanted better returns on their investments and bankers wanted bonuses.

This saw a return to the roulette of the roaring 20’s. The financial markets became a casino. It was all about betting other people’s money. Those that did, made fortunes and were heralded as sages. They didn’t make or create anything though. They gambled. They took. Of course, this all came home to roost in the 2008 crash. And the governments paid the bill and taxpayers and small investors lost out.

The 80’s were the time of Gordon Gekko and ‘greed is good’. And yes, I fell for it and moved to the UK from the US to be a part of Big Bang – a teeny inconsequential part I might add. Although I did ‘borrow’ a third of the entire long maturity, dated bonds of the Spanish government bond market, but that’s another story…. My employer made a fortune. To note, bonds with longer maturity dates have wider price swings than bonds with shorter maturity dates, so speculators love them.

The third thing was the lifting of caps on interest rates, so debt became a real money maker and a major instrument of finance. In the 80’s, credit card interest rates went to over 20%, Michael Milken and ‘junk’ bonds arrived and it was the era of Ronald Reagan – who entered office in Jan 1981 with the US as the largest creditor nation in the world and left office in Jan 1989 with the US as the largest debtor nation in the world. In the span of eight years Reagan turned things upside down and the debt age truly began. And in the UK, Margaret Thatcher spent the national assets of the UK buying elections, rather than investing in the future of the country. In Japan things were so crazy that at one point the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo was worth more than all the real estate in California. Everything changed.

Today, companies are borrowing money to pay shareholder dividends and to do share buybacks (buyback their own shares) as it drives prices up, and stock markets. They even do this when they have cash – offshore as it’s more tax efficient. Think about this. Apple has almost $300 billion cash sitting offshore (it doesn’t want to bring it onshore and pay tax) but has borrowed almost $100 billion in the past two years to pay shareholder dividends and buy its own shares back. In 2015 alone, US companies paid over $1 trillion to shareholders in share buybacks and dividends, while wages remained flat.

Companies who don’t have the cash offshore are also doing this. They are going further and further into debt to pay shareholder dividends. Yet, because they are paying dividends, the share price is going up, which means, you guessed it, they can borrow more to pay more dividends. And we all know how this will end – crash, government bailout, ‘austerity’ for normal people, rich getting richer, middle classes getting poorer.

Much of the wealth of the super-rich has been fuelled by debt, the debt of the bottom 90% who need to borrow to buy and rent things that the super-rich sell and rent to them. And let’s not forget the taxpayer-funded government borrowing that’s needed to support the super-rich casino games.

The fourth item is derivatives. Warren Buffet, the world’s most famous investor and periodically the world’s richest person, says ‘derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction’. He’s right of course. He invests by going long and often holds onto shares in companies for decades.

Someone pays a fee to guarantee that they can buy or sell something in the future at a price fixed today. This is a useful financial tool as you can reduce uncertainty by paying to fix a price today, to hedge against future price fluctuations.

Futures can be important and useful instruments and the biggest futures exchange is in Chicago. They were primarily used for physical goods, commodities – crops, animal stock, oil, minerals etc. We’ll address these first.

Imagine you’re a wheat farmer. You’d like to sell next year’s harvest at today’s price to remove the uncertainty of what the actual price may be in the future. You know your costs next year and will make a profit, so you are willing to pay today to guarantee that profit. It makes life more certain for you. You are willing to give up the chance that the price of wheat goes up and you could make more money by neutralising the risk that the price of wheat may go down and you could lose your shirt. You are not a speculator or gambler after all, you’re a farmer. You want to guarantee, to set tomorrow’s price today. You want to hedge the risk.

On the other side of this equation is a bread manufacturer. They are happy with today’s price of wheat and they can make a profit at this price without having to raise the price of bread to their customers. Sure, they could make more money or charge their customers less for a loaf of bread if the price of wheat went down, but they could also be forced to pay more and raise prices if the price of wheat went up. They would rather remove the risk of the price of wheat in the future and hedge themselves by buying tomorrow’s wheat at a price agreed today. They have price certainty. After all, they are not speculators or gamblers, they are bread makers – they want to guarantee, to set tomorrow’s price today.

As you can see, this makes a lot of sense. It removes future uncertainty. You pay to hedge the future.

Then, there are options. They are similar to futures with one big difference. They are not based around something physical, but rather around a financial instrument. They are based around shares and bonds. They give someone the ability to buy or sell a share or bond in the future, at a price agreed upon today.

For instance, an insurance company may know it will need to sell some shares in the future to meet some outflows due to some large upcoming insurance claims. These outflows can be met at today’s price and they would prefer to remove the uncertainty of tomorrow’s price. They buy an option to sell the shares at today’s price.

Conversely, perhaps a pension fund has funds coming in monthly and would like to buy shares in a company they like. They like today’s price as it gives them a certain return, so because they would like to fix tomorrow’s price today, they buy an option doing exactly that.

The reality though is that derivatives quickly became speculative instruments and ever more complicated. People used options to bet on price movements by buying or selling options. And they went from being based on shares and bonds to interest rates, stock indexes and more. Then, the financiers hired PhD mathematicians and physicists and derivatives became very, very complicated. They began to combine all types of things together and to create new derivatives that could be based on anything, such as the $/£ exchange rate vs. the price of gold vs. the length of women’s skirts (why not) vs. the price of wheat futures.

Derivatives are complicated financial machinations that no one understands, even probably the people who wrote them. Derivatives take options to a whole new level by creating financial instruments based around lots of variables. So many in fact, that no one actually knows who’s liable for what. Which is what happened in 2008.

If you really want to know what caused the crash of 2008 watch The Big Short. It was due to derivatives based around dodgy home loans.

In a nutshell, a bunch of investment bankers invented a new game of pass the parcel based on ‘derivatives’ around home loans. These were called CDO’s (Collateralized Debt Obligation). Retail bankers loaned easy money for over-valued homes, to people who couldn’t afford them. These loans were bundled with other loans, repackaged and resold to investors as CDO’s.

Some retail banks got rid of their risk and made money by selling the loans to investment banks that packaged them up and sold them to investors. Some banks formed just to give out these risky subprime mortgages and earn fees by selling them to the investment banks.

The credit rating on these loans would be very low (subprime) if they were marketed by themselves so in order to sell them, the investment bankers dressed them up by including them with other loans and having someone else guarantee them.

Investment bankers convinced other retail banks, and insurance companies like AIG in particular (at the time the world’s largest insurance company with $1 trillion in assets), to guarantee these subprime instruments by using their balance sheets and a derivative that is called a ‘Credit Default Swap’. They made the subprime loans look better to investors than they were – claiming they removed risk for investors. Investors were betting on AIG, not the subprime loans. AIG made money by agreeing to let investment banks use their balance sheets. AIG thought they were safe. They weren’t. To add insult to injury, AIG invested some of their fees and profits into, yes you guessed it, subprime mortgages. They’d thought it was easy money.

The subprime loan wasn’t what was on the table to investors; it was AIG everyone was looking at. This combined with rating agencies that gave these loans very high safety investment ratings, due to AIG, were essentially a charade. The credit agencies did not look closely at the underlying loans.

The banks made fees and investment bankers made a fortune buying and selling these instruments to investors – until homeowners stopped making payments. The subprime loans lost their value and AIG and others had to stump up. It was the end of AIG, which received an $85bn bailout from the US government. Similarly, General Electric (GE) became a huge financial player by lending money. GE settled with the US government with a fine of $1.5bn in 2019 for its involvement in a subprime mortgage bank it had owned, but luckily sold, before everything went tits up.

The market crashed and AIG, and others who guaranteed the loans or were giving subprime loans, went bust. And the government and taxpayers bailed them out. Governments around the world printed money like there was no tomorrow and called it ‘quantitative easing’. Trillions of dollars were printed and used to purchase bonds so as to stop a 1920’s type crash.

The investment bankers, who were responsible for this, were all laughing in their beach houses, which they kept. And then, as ordinary people suffered through ‘austerity’ and had no money, the rich bought all the cheap assets. They were the only ones with cash.

All this needs to be reined in and put in check otherwise it will happen again. And again.

https://prospect.org/article/neoliber...

https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...

https://www.theguardian.com/commentis...

https://www.businessinsider.com/us-bu...

Makers and Takers: Rana Foroohar

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/japans-p...

https://www.thebalance.com/apple-stoc...

Makers and Takers: Rana Foroohar

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1596363/

https://insight.kellogg.northwestern....

https://www.investopedia.com/articles...

https://www.housingwire.com/articles/...

The post How We Got into This Financial Mess appeared first on come the evolution.