An Interview with Tom Zoellner

Tom Zoellner should be on your radar for his book Uranium, and if not that then his The Heartless Stone. The former's about what the title says it'll be about, and the latter's an earlier work about diamonds and the diamond industry. Both are fantastically good books: Zoellner's among the group of microhistorians who can take seemingly inertly boring objects and tug riveting stories from their histories.

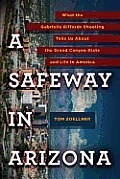

His latest, however, is a harder, sadder, couldn't-see-it-coming book. A Safeway in Arizona is Zoellner's book on, at the most basic level, the Gabby Giffords shooting, though limiting the book to that boilerplate is like saying Infinite Jest is about tennis. A Safeway in Arizona is a book which tries to take measure of the various factors that led to that morning in Arizona when a clearly troubled young guy opened fire. What is it about America, and Arizona in particular, that makes such a catastrophe possible? In chapters which examine the infamous Sheriff Joe, talk radio, the ease of purchasing a firearm, the community college which Laughner'd attended, and the come-reinvent-yourself, don't-worry-about-community atmosphere that's been Arizona's calling card seemingly since its statehood, Zoellner, with tenderness, and while involving himself (he loved Gifford; they've been friends for years) in the narrative, offers no answers, but provides a markedly new way to consider atrocities like these.

His latest, however, is a harder, sadder, couldn't-see-it-coming book. A Safeway in Arizona is Zoellner's book on, at the most basic level, the Gabby Giffords shooting, though limiting the book to that boilerplate is like saying Infinite Jest is about tennis. A Safeway in Arizona is a book which tries to take measure of the various factors that led to that morning in Arizona when a clearly troubled young guy opened fire. What is it about America, and Arizona in particular, that makes such a catastrophe possible? In chapters which examine the infamous Sheriff Joe, talk radio, the ease of purchasing a firearm, the community college which Laughner'd attended, and the come-reinvent-yourself, don't-worry-about-community atmosphere that's been Arizona's calling card seemingly since its statehood, Zoellner, with tenderness, and while involving himself (he loved Gifford; they've been friends for years) in the narrative, offers no answers, but provides a markedly new way to consider atrocities like these.

I of course would be interested in this book regardless of my background, but the fact that I was at Virginia Tech on 4/16/07 certainly influences my interest in this topic—not in catastrophes, but in looking at them and considering more than knee-jerk, most easily denounced factors. What Zoellner's offering in this book is a consideration of the factors as a whole which lead to his friend being shot in the head (along with six others dead and 18 others wounded)—how did the factors add up. It's a hugely sad—the pages feel thick with a friend's grief—and necessary book (here's Slate's take, for the record). I was lucky enough to spend some time on the phone with Mr. Zoellner at the end of December and, compressed a bit for clarity, the following's the interview.

You're in LA now, right? Why LA? And what, in general, is your biographic story—you touch on this in the book, of course, but any more color'd be great.

I'm in LA now because I took a job at Chapman University. My story in brief is that I'm from Arizona and I wanted to get the F out of AZ for various reasons. I wound up at Lawrence University, in Appleton, WI—which is not a perfect school, but it's what I needed at the time. After graduating, I worked for really small newspapers for quite a while and then ended my journalism career in 2003 at the Arizona Republic.

I'm really curious about this book—I think it's incredible, and hugely moving, but I'm curious how you did it—literally, how'd you put it together, how'd you make decisions about a book which is so clearly deeply felt and personal. Was there anything like a model you had to work with? Also: you were finishing a book right before the shootings, right? You mention that in the book.

The book came of a firm belief of mine that most events don't happen in isolation, but they're embedded in a fabric of contributing factors. And so when I started to write the book it was without any model in mind, but only a couple of vague but strong beliefs. I really didn't know what I was doing—I was working from the knowledge/certainty that there was something important to say here. It came out in a way that's somewhat rough but unpolished. The other thing to know is the book was written very quickly—essentially in four months.

The book I was working on—which was finished just a couple days before Gabby was shot—is a book called The Train. It's a biography of the railroad, how it irrevocably changed the world in ways we can't or don't fully understand. A navigable landscape, far-flung nation states—none of that would be possible without railroads. This is an invention which made it possible for humans to travel faster than a horse could run. Prior to trains, transit required muscles, wind, or water, then here's this machine which might have even been invented by the Romans (there's evidence that they were, before the fall of the empire, close to building a crude system), but it wasn't till the 1820′s that it all came together.

How hard was it to allow yourself to become part of the story? And I don't know how to ask this, but I wonder about the difficulty of this book—you mention in the acknowledgements that you sort of had to be convinced to do this. How much reluctance did you feel as you wrote, or as the book came up to being published?

When you're a newspaper reporter covering a story in which you're involved, there's always a disclosure, for ethical reasons. My entanglement with Gabby, both in friendship and in a political way, had to be disclosed, if only for ethical reasons. But the disclosure says something which I think plays into the point of the book, which is ultimately, openly about human connection. The urge toward isolation and privacy—it's not necessarily a bad thing, but there's a narrative in Arizona that tends to drive people apart. And I had a lonely time of it in Arizona—some of it was my fault, another part of that was that I don't think it's is a landscape that's particularly concerned with forging communities that foster a sense of connectedness. And Arizona's not a weird, freakish outlier; this has been going on for years in the US.

Just to round this out: there was this innate belief that Gabrielle had that we have to build people who have this common belief, she is such a wonderful maker of friends—she befriended me—who had a different set of values. I've always been about having a distant, superficial relationship with community, to sort of observe and understand but not really take part—which is a journalistic pose—and Gabby was more about get in and get your hands dirty, plant crops, live there. That was a revalation. She embraced Tuscon in a way I never did. Going to work for her was such a privelige, such a new thing for me.

As far as difficulty or reluctance: the only reason a book should exist in the world is because it's necessary, because it says something insightful about the world. It should bring some greater understanding. I think this book tries to do that. But, yes, it was a hard book in a lot of ways.

The book ends up being amazing without necessarily being prescriptive or heavy-handed—I think its amazingness is actually because it refuses to say "We need to do all this." There's that last bit, right at the end, trying to bring certain aspects to this sort of set-together clarity, but nothing overt. I don't know if there's a question about all that—I just really like that you chose not to make the book's tone hectoring or combative.

I think we have to understand that ecomonic uncertainty breeds an antagonistic flavor of politics. We reflexively look for domestic enemies, but we need to understand that much of what we hear on talk radio is about entertainment—it's not a genuine search for answers. We need to look at the incredible ease of purchasing a firearm without any meaningful review as well as safety training—had, for instance, Laughner been forced even to just take an hour-long course about how to handle firearms, there's no way the shooting would've happened, either because he wouldn't have done the class, or because someone there would've recognized the mental trouble he was in.

I think we need to understand that the types of communities that are created for us are not those that we want to live in. The isolationist impulse is fixed in physical place by how our neighborhoods are configured, in sunbelt towns like tuscon, and if you add on to that the transience, the way that we restlessly move about as Americans—and I'm as guilty of this as anyone—but for every 3 people moving into tuscon, there're 2 moving out.

The other thing too is we need to recognize that there's great social value in a basic public health network. The government absolutely has a role in making sure that impoverished citizens who are mentally ill have access. In a place like Arizona where they had to sell their state capitol (for a cash hit)—these services are not glamorous, they're sort of quotidian, and nobody gets elected on this stuff, but when it's neglected, it's devastating.

I'm curious how you ended up with the structure you've got for the book. It feels wonderfully organic, like it follows a very natural course, but I'm interested in how it felt with a mountain of info.

There were a number of things to talk about, starting with the absolutely toxic campaign of 2010—this real vicious talk radio, guns, paranoia, created a sense of disquietude in the state. There's no evidence that Laughner cared about immigrants, for instance, but the shooting was connected in some way to the nastyness that was in the air after that election.

So there was mental illness to talk about, schizophrenia to try to explain, and tracing his trail in his quite miserable post-high-school life. And then there's my relationship to Gabby, and the history of Arizona, all these bits of tile that had to go into it. There was not the clean narrative through line I'd've liked.

Are you happy with the book then?

Am I happy with the book? I did the best I could. I wish the book did not have to exist. I'd give almost anything to make the thing at the Safeway not happen. Without that kind of discussion—how does this sieckening rip in the social fabric not take place—the shooting would be a greater tragedy.

Who are some other writers you like? Are there are folks who do writing that you read and think: that's along the lines of what I'm trying to do, too.

John Gunther wrote a series of books—he was a reporter for the Chicago Daily News for many years between WWI+II, and after the war he wrote a series of books called Inside Europe, Inside the USA, Inside South America, Inside Africa—doorstop length books on how a continent worked. The writing is just robust, and the deep sociology in the books still holds true.

In fiction, two of the greatest living authors are Richard Ford and TC Boyle. Boyle's medium is the short story and he's the reason I wanted to be a writer in the first place. There's also Charles Bowden, and being able to befrind Bowden has been a tremendous privelge.

One of the more fun apects of interviewing people is asking them to explain certain un-understandable things. For instance: I can ask the editor of Texas Monthly what the deal is with Texas, since I'll never, in my midwesternness, really get it. Similarly: what the hell's the deal with Sheriff Joe Arpaio?

(laughs) Sheriff Joe's very good at figuring out what motivates people on an emotional level and he is personally very compelling—he's got charisma, he's got this unabashed self regard that makes him extremely hard to dislike. He's harsh, certainly, but he's charming. It really is a certain sort of rogouish personality that's from a distance likeable. There are antagonistic universes which the sheriff creates and then uses to come in and look like a superhero. He sets up this paranoid scenario—there are dark forces that are ready to come through the window unless we've got someone to come take care of things. And he's of course that someone.

And, of course, Sheriff Joe's work is the opposite of the slow, boring work to build compromises or structures that're necessary to do real policy, to get things done.

But Joe's got great appeal to voters who are disconnected from their communities, or those that are just passing through and may not even be voting anyways—the center tends to slip to the extremes in primaries, and you have the quality of electing people based on fear or emotion rather than competence. You see this just a little bit clearer focused in AZ—because of disconnectedness, and the high grade of newcomers, the high grade of paranoia. People in Arizona are bellwethers for some of the more troubling aspects of life in the US.