Isolation story: (18) The Caramel Forest

It can be pretty isolating to be the child of parents who aren’t getting on. I feel sorry for families right now who are in that position.

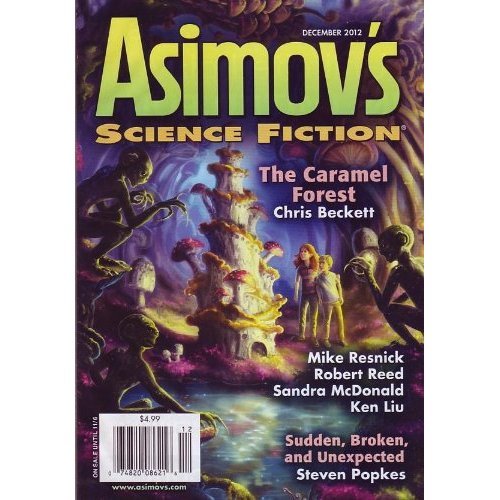

This was the cover story in Asimov’s SF in 2012 (the artist was Laura Diehl). It was subsequently collected in The Peacock Cloak, along with another story, ‘Day 29’, which was also set on the imaginary planet Lutania.

Lutania is the prototype for the setting of my most recent novel, Beneath the World, a Sea. In the novel, however, I moved it from an alien planet, to a remote place in South America, the Submundo Delta where life is entirely different to, and completely unrelated, to life anywhere else on Earth.

The Caramel Forest

In the

caramel forest the leaves, trunks and branches were all made of the same smooth

flesh, like the flesh of mushrooms. It

was yellow, grey or pink. A kind of

moss covered the ground, pink in colour, and also fleshy and

mushroom-like. And there were ponds,

every hundred yards or so, picked out by the pale sunlight that elsewhere in

the forest was largely filtered out by trees.

The ponds were surrounded by clumps of spongy vegetation, pink or white

or yellow.

But the children, pressing their faces to

the car windows, were trying to spot something more interesting than trees and

ponds. Cassie told Peter he would win

five points if he spotted an animal of some kind, and one hundred points for a

castle. They’d only ever seen one of

those and that had been in ruins, its delicate, butterscotch, shell-like

architecture smashed and kicked to pieces by settlers.

But the forest, with its spotlit ponds,

remained an empty stage. There were no

castles, and no animals either, only the occasional solitary floater drifting

through the space between canopy and forest floor, trailing its delicate

tendrils, and bumping from time to time against the trees. Cassie didn’t consider floaters either

sufficiently animal-like, or sufficiently interesting to deserve a point.

‘We see those all the time,’ she told her little brother, who nevertheless persisted in pointing them out.

‘Those aren’t really ponds, you know,’ she presently informed him. ‘Under the ground they’re all joined up. It’s like a sea covered over by a roof of roots and earth.’

‘Quite right, Cassie,’ said her father, David, from the front passenger seat.

‘I wish we’d see some goblins,’ said Cassie, glancing defiantly at the back of her mother’s head. ‘I’ll give you twenty points, Peter, if you spot us one, and I’ll let you have turn with my microscope as well.’

‘We don’t call them goblins, do we?’ David reminded her. ‘We call them indigenes. They’re just living creatures like us, going about their lives.’

‘Everyone at school calls them goblins,’ said Cassie.

‘Well, most kids in your school are the children of settlers,’ said her father, ‘and they don’t know any better. But we’re Agency people. We’re supposed to set a good example.’

Another floater (which Peter, annoyingly, still pointed out), more ponds, more silent empty space beneath the mushroom-like trees.

‘Most of the kids say that goblins are only good for shooting and nailing up,’ Cassie said off-handedly. ‘They say the Agency is soft.’

‘Well that’s just silly, Cassie. There’s no reason to persecute the indigenes. They harm no one, and they were here for millions of years before the first settlers came.’

‘They give you funny ideas though.’

‘Well, maybe. But that’s probably just their way of protecting themselves.’

‘Protecting themselves?’ Cassie weighed this idea for a moment, tipping her head to one side, then dismissed it with a shrug. ‘Well whatever it’s for, I…’

‘Must you talk about those horrid things all the time?’ interrupted Cassie’s mother, Paula.

She turned a corner, leaving it rather too

late, and the car only narrowly avoided a particularly large pond, a small lake

almost, with the road running along the edge of it. David winced, but did not comment.

Peter pointed out two more floaters

drifting by above the water.

‘You’d better play in the garden when we get back,’ Paula said, half-turning her beautiful but bitter face as they left the pond and headed back into the trees. ‘I need you out of the way so I can get ready for the visitors. We’ve hardly got enough time as it is, let alone with you two getting under my feet.’

‘Honestly Paula,’ David whined. ‘I can’t win. You keep saying how bored and lonely you are. I thought you’d appreciate the company.’

‘Yes, David, but it was just stupid to invite people to come to dinner at 6 o’clock, when you knew that we ourselves would still be two hours’ drive away at 3.’

Cassie tensed. She dreaded her parents’ quarrels.

‘And anyway,’ Paula went on, ‘my idea of company is people who might be interested in talking about things that I like talking about. Not two of your workmates who will just talk shop.’

She sighed.

‘And one of whom you obviously fancy,

incidentally,’ she added, ‘ judging by how often you mention her name.’

‘For god’s sake Paula. What was I supposed to do? They called me. They said they’d be passing our way. They asked if we’d be around.’

‘You could have said we were doing something else. You don’t seem to find that hard to say that to me.’

‘Let’s sing some songs,’ Cassie said firmly to her brother.

* * *

The

bungalow sat in the middle of a wide bare lawn, surrounded by a two-metre chain

link fence to keep indigenes and animals at bay, with floodlights on poles at

regular intervals. The lawn, rather

startlingly, was green, a colour entirely absent from the surrounding

forest.

Juan, the caretaker, sat outside his hut

cleaning a gun. He laid it down and

limped to the gate to open it for them, nodding, but not smiling, as they

passed through.

‘Bo da, senar senara,’ he greeted them with small stiff bow. He could speak English well enough but usually confined himself to Luto.

Cassie organised a game outside in which

Peter was a dog called Max, and she was the dog’s owner. Peter was five. She was ten.

‘Woof! Woof!’ said the dog.

All around them was the silent forest. It had a strong sweet smell, like caramel, but with a faint whiff of decay.

‘Woof! Woof! Woof!’

‘Quiet now, Max, I can’t hear myself

think.’

It was odd. The one thing Cassie did not want to hear were the sounds of shouts or sobs from within the house, and if she had heard them, she’d had covered them up at once with noisy play. Yet she couldn’t help herself from listening out for them: listening, listening, listening, all the while glancing down the road back into the forest on the far side of the chain link fence, willing their visitors to arrive.

But the forest, that silent, waiting,

spotlit stage, was still. Nothing made a

sound. Nothing moved except for yet

another floater drifting through the trees.

‘We’re on an alien planet,’ Cassie informed her dog Max, who was too young to remember anything else. ‘This is Lutania. We come from Earth, where the trees are green like this grass, and there are no goblins or unicorns, and none of the creatures can talk to you inside your head. One day we’ll go back there, across all that huge huge empty space. Imagine that.’

Was that a sound from the house? She held up her hand to tell her brother to be quiet. But no. It was just something banging in a gust of breeze in the garden of the other house behind hers, the empty house, which, apart from Juan’s hut, was the only other building in the vicinity. They were on their own out here. It was five miles to the next human settlement, and that was a Luto village, the one where Juan’s family lived, with no Agency inhabitants at all. School was another ten miles beyond that.

‘Come here now Max and eat this bone. If you’re good I’ll stroke your head.’

‘Woof!’ said Max, crawling obediently across to her.

‘Oh, wait a minute,’ she said. ‘Here are the visitors. You’d better be Peter again.’

* * *

Every

night, through the thin wall of her room, Cassie heard her mother crying.

‘I hate this place…,’ she’d hear Paula sob, ‘I hate this stinking forest…’

‘Ssssssh!’ her father would hiss.

Or, after half an hour of muffled sobs and murmuring, Paula would suddenly cry out:

‘Of course the kids don’t bug you when you’re away all the time.’

‘Shut up,’ Cassie would mutter, on her own in the dark. ‘Shut up, shut up, shut up.’

She’d try and distract herself by thinking

about the immense tracts of space between Lutania and Earth. If she could only understand how big that

was, she felt, this little house, and this little local difficulty of her

mother being miserable and her parents not getting on, would become so small

that they’d be of no consequence at all.

It was a bleak sort of comfort.

Peter, meanwhile, would sleep peacefully in

the room on the other side of hers.

* * *

Right now,

though, there were the visitors to attend to.

Ernesto and Sheema

‘Sorry about the short notice, but it seemed a shame not to call by when we were in these parts.’

‘Hope we haven’t put you out. Good lord, look at this spread! You shouldn’t have gone to all this trouble!’

‘Nonsense, nonsense,’ cried Paula. ‘No trouble at all. Lovely to see you. We’d have been most offended if you’d passed this way and not come to see us.’

Standing in the corner of the room, hand in hand with Peter, Cassie watched her mother with narrowed eyes. Paula really did seem pleased to see these people, that was the strange thing. She really did seem to mean what she said. She was smiling. She had laughter in her eyes. But that was how she was. You never knew. You could be laughing and joking with her one minute, thinking you were having a lovely time, and then the next look round and see her collapsed and broken, crying hopeless tears.

‘My,’ said Sheema, ‘what beautiful children!’

Cassie turned her attention to Sheema, accepting the compliment with a severe half-smile and a gracious inclination of her head. Sheema was quite pretty, she supposed.

‘Such wonderful red hair too!’ Sheema said, quailing in the intensity of the little girl’s gaze, and turning back hastily to the grown-ups.

* * *

‘Okay,

okay,’ Cassie’s father conceded over the empty dinner plates. ‘They have an electromagnetic sense. They communicate with microwaves in some

way. The trees act as antennae. I grant you all that, and I grant you that it

may allow them to detect human brain activity.

But it doesn’t explain how they interpret

it…’

‘They don’t interpret it, Dave,’ Sheema said. ‘They pick it up and beam it back to us.’

‘Sure, but you’re not getting my point. They don’t just beam back random signals, do they? They’re able to home in on certain things…’

‘Or perhaps just stimulate certain parts

of…’ Ernesto began.

David ignored the interruption.

‘And anyway, Sheema,’ he said, ‘the “beam

it back to us” theory doesn’t explain how we manage to receive the signal.’

‘You’re both complicating this

unnecessarily,’ Ernesto persisted. ‘Like

I say, they don’t receive or send a signal;

they just stimulate certain parts of our brains. They disorientate potential predators by

stirring up uncomfortable feelings. They

don’t have to know what it is they’re dealing with, any more than a chameleon

has to know that the red thing it’s sitting on is a tablecloth. It just copies the colour.’

Peter was already in bed. Cassie knew she would soon be sent to bed as well. She glanced between the adults with sharp appraising eyes. Dad and the two visitors were talking louder and louder as the evening went on, and crossly interrupting one another more and more, and yet they were smiling too. They seemed, for some reason, to be having fun. Mum was a bit quiet – she wasn’t a scientist like the other three – but even she was smiling. She did seem very thirsty, though. She was drinking glass after glass of wine.

For a moment, David glanced uneasily at his wife, noticing warning signs. But he returned to the argument all the same.

‘What you’re stubbornly missing, Ernesto,’

he said, laughing angrily and banging his hand on the table. ‘What you’re refusing to consider is

this. How can a creature whose nervous

system is absolutely nothing like ours at all, home in on our “uncomfortable

feelings” and stir them up? One can just

about envisage how they or their trees might do this with other Lutanian

creatures with similar nervous systems.

But with humans? How? How are they able to locate those feelings

in our quite different brains?’

‘A good point,’ Sheema acknowledged with a laugh. ‘But what alternative are you suggesting?’

‘I suspect we may eventually need an entirely new theory of the mind. Think about it. We have completely different brains from goblins.’ (For some reason, he was using the word freely, though he always corrected his family when they used it.) ‘They don’t even have neurons, as we understand them – they don’t even have an analogue of neurons – and yet indigenes are able to reach right through the species-specific particularities of the human brain, to find and stimulate the places where we keep our troubles. How can this happen unless pain and distress has some kind of universal form that transcends the particular nervous system which expresses it? And that being so, perhaps we need to radically rethink the place that mind has in the scheme of things. Perhaps we need to stop speaking about space-time, and starting talking about space-time-mind.’

‘But that’s mystical nonsense, David,’ laughed Ernesto, angry and friendly all at once. ‘With great respect, it’s just lazy mystical nonsense. Just because we’ve failed so far to find an explanation in terms of the parameters of physical science, it doesn’t mean we have to give up and rewrite the entire rulebook.’

‘Why not, Ernesto? Why not at least consider that possibility? Space, time and mind.’

David’s eyes were bright. He was in a playground where he felt at home, and he was full of energy, with the cowering, haunted look, so often there, quite absent from his face. But he was careful to avoid looking back at his wife, whose eyes were shining in quite another way.

‘Because it’s twaddle David,’ Ernesto laughed. ‘It’s mystical twaddle!’

Paula rose to collect the plates.

‘Are we ready for dessert?’ she asked in a

loud bright voice that Cassie recognised at once as dangerous.

David glanced at her. There was a brief flash of fear in his eyes, but he still turned back stubbornly to his friends.

‘One other point, Ernesto. One other point that people sometimes

forget. We’ve been assuming this evolved

as a defence against predators, but what predators exactly do we have in

mind? It’s not as if…’

‘That was delicious, Paula,’ cut in Sheema, glancing with sudden anxiety at her hostess. ‘I’ll come and help you.’

‘What was it you were saying about

goblins?’ Cassie asked the two men as

the women left the room. ‘What were you

saying about their minds?’

‘Indigenes, darling,’ said her father, barely concealing his irritation at being distracted. ‘Yes, we were just talking about how they somehow make people have uncomfortable thoughts when they get up close.’

‘They don’t make me have uncomfortable thoughts,’ Cassie said.

‘Ah, well maybe you haven’t been near enough to one,’ suggested Ernesto, with a friendly wink.

‘I have so, loads of times. Here and at school. One came right up to the school fence a couple of weeks ago. I liked the thoughts it gave me.’

‘Did you indeed, sweetheart?’

Her father glanced at Ernesto, smiling and

raising one eyebrow in a superior and theatrical way that Cassie knew was only

made possible by the presence of visitors.

She shrugged.

‘It happened, Dad,’ she said coldly. ‘Whether you choose to believe it or not. I liked being near it. But the other kids threw stones at it.’

David laughed uneasily, glancing again at his friend.

‘Nearly time for bed,’ he announced.

‘I haven’t had my pudding yet.’

There was a loud wail from the kitchen.

* * *

‘They’re

out there again!’

David rushed to his wife. Cassie hurried after him.

They could see the goblins through the kitchen window: two of them, one squatting, one standing.

‘Make them go!’ sobbed Paula. ‘For God’s

sake make the horrible things go away!’

They were thin grey creatures, about the

same height as Cassie, picked out by the bluish electric lights around the

fence. Neither one of them was looking

at the house. Both seemed engrossed in

some object that the squatting one was holding up for the other’s inspection: a

shell, perhaps, or a piece of stone.

‘Get a grip now Paula,’ muttered David. ‘They’re completely harmless.’

Sheema put her arm round Paula’s shoulders.

‘Easy now, love,’ she said in a warm and

gentle voice.

But the look she gave her husband wasn’t

warm at all, and seemed to Cassie to refer to some prior exchange between the

two of them. Sheema hadn’t wanted to

come here, was Cassie’s guess: Sheema had warned Ernesto that Paula would be

difficult and make some sort of scene.

David and Ernesto went out through the kitchen door and starting running across the unnatural green of the grass towards the fence, shouting and waving their arms, each one of them with his own set of multiple shadows thrown out by the floodlights.

‘There there,’ Sheema murmured soothingly

to Paula. ‘There there. Remember it’s just a silly trick they

play. Just a silly trick they play on

our minds.’

Cassie

stepped just outside the kitchen door, so she could watch everything: the women

indoors, the goblins and men outside.

The caramel smell wafted from the forest, carrying its faint hint of

decay. The moss under the trees glowed

softly. The many ponds shone with

phosphorescence. And creatures were

moving out there, whichever way you looked.

The stage was no longer empty.

‘Go away!’

David ran up to the fence, kicking it and

banging on it with the flats of his hands.

After a few seconds, the squatting indigene rose very slowly to its

feet, and then both it and its companion turned their narrow faces towards

David and regarded him with their black button eyes. Their V-shaped mouths resembled the smiles in

a child’s drawing.

‘Go on, be off with you!’ David shouted

again, quite pointlessly, for the creatures had no ears.

Both goblins tipped their heads on one side

– sometimes indigenes could look thoughtful and cunning; at other times they

seemed as devoid of intelligent thought as a tree or a toadstool – but neither

of them moved away. Behind them, far

off in the softly glowing forest, a column of white unicorns was making its way

through the trees.

Cassie started to walk down towards the

fence.

‘Cassie darling,’ called Sheema without

much conviction. ‘Don’t you think you

ought to…’

She tailed off – she had no confidence with

children – and in that same moment Cassie heard in her head the voice that

always spoke in the presence of goblins: her own voice, speaking her own

language, but not under her control.

‘Fear,’ it said, ‘but no love.’

Again David banged impotently on the

fence. It had no effect on the goblins,

but it brought Juan out of his hut, swearing in Luto, with a heavy pulse gun in

his hands. He limped to the fence and

pointed the gun at the goblins at point blank range, barely acknowledging his

employer or his employer’s guests.

‘Be careful Juan,’ began David, ‘no need

to…’

Ignoring him, Juan pulled the trigger. The gun only made a faint thudding sound, like a beanbag dumped on a table, but the goblins staggered and clasped their heads.

‘I think that was excessive Juan,’ David said, as the creatures loped off into the forest.

‘You want them to go or not, senar?’

Juan shrugged and turned back to his

hut. Cassie knew his children – they

went to the same school as her and Peter – and she knew that, if Juan had been

given the choice, he’d have killed the goblins without compunction, or maybe

caught them and nailed them to a tree. It

was what Juan and his friends did for fun when they went hunting out in the

forest, with no Agency do-gooders there to pry or to spoil things.

David and Ernesto walked back to the

house. Cassie, unnoticed, followed

behind them. She could see how David

deliberately turned slightly away from his friend, so Ernesto couldn’t see the

strain in his face.

‘So?’ asked Ernesto. ‘What did you

hear in your head, David? What wisdom

came to you through the channel of pure mystical being?’

‘I didn’t pay much attention,’ David said shortly. ‘You know what, though. I really wish Juan would listen to me a bit more, and do what I ask him to do, instead whatever he happens to think best. The Agency pays his salary after all.’

He still hadn’t noticed his daughter following quietly behind them.

‘I heard the voice telling me that I was second rate,’ sighed Ernesto, ‘and that no matter how hard I tried, I would never be as good a scientist as you.’

In the kitchen, Paula was sobbing on

Sheema’s shoulder. No one asked her what

she’d heard in her head.

David noticed Cassie and told her to go to

bed.

* * *

Some nights

were sobbing nights. Some were sniffing

and snivelling ones. But that night,

after Sheema and Ernesto had gone, was the worst kind. Tonight was a wailing night.

‘I can’t stand those things, David. I can’t stand them. Can’t you see that? I just can’t bear another whole year of them. Why can’t you get that? Why doesn’t it matter to you? I know you don’t love me, but don’t you care about me one little bit? Don’t you care at least about the children?’

‘The children are fine with goblins, you know that. And please keep your voice down, or Cassie will hear us.’

‘They’re not fine with goblins. You really don’t understand anything do you? Cassie pretends she’s fine with them as way of coping and trying to keep the peace.’

‘No I don’t,’ hissed Cassie in the darkness. ‘Stop lying about me. Stop lying.’

She banged angrily on the wall. Her parents’ voices subsided immediately to a murmur, but she knew the wailing would soon start up again.

‘Run away, why don’t you?’ asked a

voice inside her head. ‘Why hold on to

this dream?’

She went to the window. Sure enough, the goblins had come back. They were squatting side by side with their backs against the fence.

Cassie sighed. It was only a matter of time before Paula also sensed their presence, and then there would be no peace at all.

* * *

‘My

dad said you had goblins round yours last night,’ said Carmelo next day in the

school playground.

Cassie was in her usual refuge, a

place close to the fence where she could squat down behind a spongy clump of

pink vegetation and be shielded from the general view. Juan’s son had come over specially to seek

her out. He was dark and wiry, with

clever mocking eyes.

Cassie shrugged. ‘Yeah, we did. I didn’t mind though. I quite like them.’

Beyond the fence lay the silent,

empty forest.

‘You quite like them?’

The boy took a cigarette from his

pocket and lit it. He was only eleven

but he drew the thick soupy smoke into his lungs like a smoker of many years, releasing

it slowly with a contented sigh.

He squatted down beside her.

‘Dad said your mum yelled and

yelled when those goblins came back again in the night.’

‘Yes, she did. We had to get your dad out of bed again to

chase them away. Mum hates goblins.’

‘Well, that makes one person in

your family who’s got a bit of sense.’

‘Why? What’s the harm in goblins?’

‘They slowly take over your head,

Agency girl. Slowly, slowly. Funny thoughts and dreams: that’s just the

beginning. Next thing you know, you’ve

forgotten who you are or where you came from, and then you belong to them. That’s why we shoot them and string them up. We’d be goblins ourselves if we didn’t.’

He drew in more smoke and regarded

her with narrowed eyes as he let it back out through his mouth and nose. The two them were still only children, but

there was a certain electric charge between them all the same. Carmelo constantly mocked Cassie for her stuck-up

Agency ways, and she scolded him for his ignorant settler beliefs, and yet he often

sought out her company like this, when he could have stayed with the other

settler children, or brought them over to tease her.

‘But you’re not allowed to harm goblins,’

she told him primly. ‘It’s against the law.

You’re supposed to treat them like people.’

Carmelo made a scornful noise.

‘Like people! We’ve been dealing with goblins here since

long long before your Agency came along with its stupid laws. My dad

says, when he was a kid, every single village had dried goblins nailed up on

gibbets at the gates to warn the others away.’

He drew deeply on the cigarette,

regarding her carefully.

‘Goblins were here long before you

were,’ Cassie pointed out.

Carmelo laughed as he released the

smoke.

‘And we were here long before you,

Agency girl. And Yava gave us this world.’

Yava was the settlers’ god, and

Cassie knew from experience that there was no point in even discussing him.

‘You shouldn’t smoke, you know,’

she said. ‘It’ll mess up your lungs.’

‘Don’t

do this, don’t do that!’ the

settler boy mocked her, and took another deep drag. ‘You agency people are all the same.’

‘Well it is bad for you. That’s just

the fact of it.’

Carmelo exhaled.

‘Those goblins didn’t come back

again after their second visit, did they?’

‘No. Not after your dad chased them away again.’

The boy snorted.

‘Chased them away!’

‘What? What’s funny about that?’

‘He chased them out of your sight,

more like, and then did for the two of them with an axe. That way he got to sleep the rest of the night,

without your mum and dad yelling for him every hour or so.’

Cassie stared at him.

‘He killed them?’

‘Of course he did.’

‘But we didn’t want that!’

‘Oh come on, Cassie, they’re only

animals.’

‘How could they take over our minds

if they were only animals?’

But Carmelo had spotted a floater

drifting in over the fence. Taking one quick

final drag from his cigarette, he took careful aim and flipped the glowing butt

end upwards. There was a hiss of gas as

the burning tip made contact, and then the floater sank, slowly deflating, onto

the ground.

Carmelo walked over to it, and

squeezed out the remaining gas with his foot.

* * *

One

night, a month or two later, Cassie was woken in the early hours of morning by

her parents quarrelling yet again on the far side of the bedroom wall.

‘Why don’t you listen, David? I – don’t – want – to – stay! Which part of that don’t you understand?’

She got up and went to the

window. The lawn outside shone its unnatural

green in the bluish glow of the electric lights. Far off in the forest, tall shadowy giraffe-necked

creatures were solemnly processing round a shining pond.

‘Why is it impossible, David, why?’ came her mother’s voice. ‘Why can’t you just go to the Agency and say

“sorry, we made a mistake, we need to go home before my wife loses her mind,

and my kids become even more weird and goblin-like than they already are”? Why is that impossible?’

Cassie considered knocking on the wall

as usual. Her parents had already had

one row that night. Surely they could

see it wasn’t fair to wake her up again?

But she didn’t do it. Something in her mind had clicked into a new

position, though she couldn’t have said why, just now, after months and years

of this nightly torment. Giving a little

firm nod of assent to her own impulse, she pulled on some clothes, and tiptoed

quietly to the door. As she touched the

handle, her mother’s voice rose yet again in the next room.

‘I know David, but what you’ve got to understand is…’

She closed the door carefully

behind her.

* * *

Her

brother woke with a start.

‘Peter. Wake up.

We’re leaving.’

‘What?’

He always obeyed his sister

unquestioningly, but he’d been deeply asleep.

‘Where are we going?’ he wanted to

know, while Cassie passed him clothes.

‘Away from here. Mum’s shouting at Dad again.’

Cassie took the key to the compound

from the shelf beside the kitchen door, then crept out across the grass with

her brother, bleary-eyes, behind her. She

slid back the bolt on the gate, very slowly and carefully so as not to disturb

Juan, then led Peter briskly through.

She headed quickly away from the brightly lit fence and then immediately

off the road and into the forest.

‘Dad says you could walk five

hundred miles this way,’ she said, ‘and still not reach another road.’

All around them were ponds, and

phosphorescent moss, and creatures moving under the dim mushroomy trees.

‘Where are we going?’ Peter asked again as he

trotted behind her.

‘I don’t know yet,’ Cassie said. ‘But don’t keep asking me, eh?’

From a pond straight ahead of them,

unicorns emerged, scrambling one by one out of the bright water to snuffle and flare

their nostrils in the caramel air, before heading off in single file through

the trees.

Peter began to count them.

‘One, two, three, four…’

‘Seventeen,’ Cassie told him

shortly.

* * *

About

twenty ponds later, they came to one where a single, very small, goblin sat at

the bottom, lit by the pink phosphorescence of the pond’s floor. The creature was not much bigger than a large

cat, and was quite motionless, staring straight ahead, apparently at nothing in

particular.

Peter pulled at his sister’s hand, troubled

by the presence of the goblin and wanting to move away. But Cassie resisted, making him wait until

the little goblin glanced up, its black button eyes taking in the two of them looking

down from the air above.

‘Mummy is going mad,’ said a calm

cold voice inside Cassie’s head. ‘Daddy

is a scaredy-cat, who hides away at work.’

‘Yes, sirree,’ she muttered with a

grim chuckle. ‘You got that right, my

friend’

Peter began to cry, and Cassie

turned to him with a frown.

‘Go on then,’ she said, ‘Spit it

out. What did it say to you?’

Her little brother just sobbed.

‘Well, whatever it said,’ she told

him firmly, ‘you may and well face up to it, because it’s true. They don’t tell lies.’

Peter nodded humbly.

‘So go on then,’ Cassie persisted. ‘Tell me what it said.’

‘It said…’ snuffled Peter, ‘it said

that Mum wishes I’d never been born.’

‘Oh that,’ Cassie snorted. ‘Is

that all? I

could have told you that. I’ve heard it often

enough through my bedroom wall. She

wishes she hadn’t had either of us. Spoiled

her career apparently, and anyway she doesn’t like kids. Come here, you silly boy. Come to big sis. I

love you don’t I?’

She pulled Peter close to her, putting

her arm round his shoulder in a rough masculine way. Three baby water dragons appeared in the pond,

supple as eels and slender as human fingers, and began to chase one another round

and round the little goblin, which was once more staring straight ahead.

‘There you are, Peter,’ Cassie said,

hugging her brother against her, and absent-mindedly patting him. ‘There there.

That’s better isn’t it? You’ve

got me to look after you, haven’t

you? You’ve got your big sis. So you don’t need them, do you? You don’t need anyone else at all.’

Peter sniffed and nodded.

‘There’s all the food anyone could

want out here, after all,’ Cassie told him, giving him a little encouraging

shake. ‘We’ll be quite happy having fun out here all by ourselves. No Mum blubbing. No Dad whining.’

She thought for a moment, a little

sadly, about Carmelo.

‘And no horrid school with settler

kids,’ she added firmly, ‘who think killing things is fun.’

At the bottom of the pond, the goblin

suddenly swum off, disappearing, in a single, frog-like stroke, into one of the

water-filled tunnels under the trees.

‘Come on then, trouble,’ Cassie said to her

brother. ‘Let’s get moving again, before someone notices we’ve gone.’

* * *

All

that night, with pauses for food and rest, they wandered through the caramel forest,

Cassie telling Peter stories to keep his spirits up, or providing him with

improving pieces of information, or making up games for them to play together. Who could find the biggest tree pod? Who would spot the next dragon?

‘Why don’t you be Max the dog again, Peter,’ she

suggested when he seemed to be flagging, ‘and then you can snuffle things out

for us.’

Snuffling things out wasn’t exactly

hard to do, with the show in full swing all around them.

‘Woof! Woof!’ said Max almost at once, spotting a

gryphon fanning a pair of incandescent wings that crackled with electric charge.

‘Woof! Woof!’ he said again, as a white hart darted away

from them, and plunged into the underground sea.

‘Woof! Woof!’ he shouted out, as an agency

helicopter came thump-thump-thumping over the mushroom trees, probing down into

the forest with long cold fingers of light.

‘Good boy Maxie,’ Cassie told her brother. ‘Good

boy. Now quickly come and hide.’

* * *

Not

long after the helicopter had passed over, dawn began to break. The phosphorescent glow faded from the moss

and the ponds, the stage emptied, and the two children found themselves walking

alone through ordinary sunlight that filtered down through the trees, as in

pictures of Earth, that faraway world across the void, that place where leaves

were green.

They lay down to sleep in deep soft

moss.

* * *

When

Cassie woke the sun was already setting.

Beside her Peter still slept peacefully, sucking the edge of one finger,

and for a while she just lay there watching the shadows of dreams rippling

across his face and his eyes darting about under his closed lids.

During the quiet still hours of

daylight, Cassie realised, creatures had come to watch her dreaming, just as

she was watching Peter now. She’d had strange

thoughts running through her sleeping mind, and a familiar voice in her head

had been telling her that there was no faraway home, no great void of space, no

‘Earth’ or ‘Lutania’, only a single, small, whispering, seething thing, strange

and familiar all at once.

From a nearby pond climbed a small winged quadruped, shaking its sparkling wings.

‘Come on Peter,’ Cassie called out gaily. ‘Wakey, wakey! It’s another lovely night.’

* * *

They

were deeper into the forest that night, further away from Agency stations and

settler villages alike, and they came across many goblins.

The creatures were sometimes on

their own, often in twos and threes. They

watched the children with their black button eyes and smiled their V-shaped

smiles. One of them held out a white

stone, another a piece of twig. One even showed them a small brown button from

a settler’s jacket.

‘There is no space,’ said the voices in Cassie’s head, as the goblin’s eyes watched her. ‘There are no people. There is no such thing as far away.’

It seemed strange to her that she’d ever been persuaded to believe in an immensity of empty space beyond the caramel forest and its sky, for it seemed obvious now that everything that existed was as close as could be to everything else: close enough to whisper and rustle and murmur, close enough to touch…

She looked at the button. She nodded. She turned away.

Peter clutched her hand so tightly

that it hurt.

* * *

Several

more times they heard the thud-thud-thud of a helicopter passing over head, and

saw the Agency searchlights sweeping officiously through the mushroom-like

trees, leaching the colour from leaves and trunks.

The children just hid until they passed, surrounded by the whispering and rustling and murmuring of the caramel forest.

Cassie had no desire to be plucked

up into the empty sky.

* * *

When

dawn came again, they came to a castle beside a pool. It was very small, only about Peter’s height

in fact, and looked at first like a little smooth stalagmite that had grown

there, for some reason, beside the water.

But one side of it was open, and they could see the intricate little chambers

inside it, with their amber whirls and coils that enclosed even smaller

chambers, and yet-tinier whorls…

When they tired of looking at it, the

children gathered the spongy vegetation that grew around the castle and made

themselves a secret nest nearby, well hidden from the sky. Then they found some savoury chicken fruit to

have for their supper and a couple of toffee apples for afters.

‘Now wash your face and clean your

teeth in the water, Peter,’ Cassie said when they’d finished. ‘And then let’s

get you settled down.’

She stroked his head and told him a

story, while the sun rose in the sky, turning as it climbed from a syrupy

rosehip red to pale lemon.

‘I’ll look after you, my little bruv,’ she whispered to Peter’s already sleeping face. ‘I’ll always look after you.’

* * *

Three

goblins arrived. One by one they

caressed the little amber castle, and bent down to stare into its

interior. Then they settled on their

haunches on the bank of the pond, without even a glance at the two children.

‘Won’t find your way back now,’

said the voices in Cassie’s head.

‘Not if I can help it,’ muttered

Cassie contentedly, stretching out in her improvised bed.

* * *

Crack!

There was a gunshot, followed by human

voices and barking dogs.

Peter lurched into wakefulness with

a whimper.

Crack!

One of the goblins dived into the

pool.

Crack! A

man ran to the bank and fired into the water.

‘Is alright now, darlings. We take you back to your Ma!’ growled another

man’s voice, right next to the children in a thick Luto accent. ‘Goblins won’t scare you no more.’

Sitting up, Cassie and Peter clung

together. The whispering and murmuring

of the caramel forest was suddenly far away.

‘And maybe this time Agency go

listen eh?’ grumbled a third man, helping Cassie and Peter to their feet. ‘Maybe this time they go understand why

goblins is bad.’

The air was full of smoke. These weren’t pulse weapons that these men

were carrying. They were proper old-fashioned

guns, blasting out deadly balls of hot, hard matter.

Dogs came sniffling and snuffling, first

round the children, and then, rather more interestedly, round some smooth greyish

stuff that was strewn over the ground nearby.

Cassie gazed at it,

uncomprehendingly.

‘Don’t worry about nothing,’ said

the leader of the search party. (It was one

of dozens spread out across the forest, linked by radio to the Agency

helicopters overhead). ‘Is only crazy

ideas these goblins put in your head.

That’s all. Only crazy

ideas. They’ll went away soon enough.’

He ruffled Peter’s hair kindly, and

gave Cassie a friendly wink. She stared

at him. The other men were breaking up the

castle with their gun butts.

One of the dogs took an experimental mouthful of the grey stuff, then sneezed and spat it out. It was goblin flesh, smooth all the way through, like the flesh of mushrooms.

Copyright 2012, Chris Beckett

Chris Beckett's Blog

- Chris Beckett's profile

- 340 followers