April 8, 1960 – The Netherlands and West Germany sign a Treaty of Settlement where German territory annexed after World War II would be returned in exchange for monetary compensation

On April 8, 1960, The Netherlands and West Germany signed an agreement whereby German lands annexed by the Netherlands after World War II

would be returned to Germany in exchange for the latter paying the former 280 million German marks as compensation for the returned lands.

In October 1945 after World War II had ended, the Netherlands asked Germany for 25 billion guilders in reparation, but retracted this as the Allies had previously agreed that no monetary reparations would be paid. The Dutch government then turned to considering a number of options for territorial compensation, the most aggressive version being annexing a sizable area of German lands, including the cities of Cologne, Aachen, Münster and Osnabrück. In the face of Allied rejection of the plan, the Netherlands agreed to just 69 km2 of German territory as war reparation.

In March 1957, the two sides started negotiations for the return of the lands. An agreement was reached on April 8, 1960. In August 1963, the lands were returned, except for one small hill (about 3 km2) called Duivelsberg/Wylerberg near Wyler village.

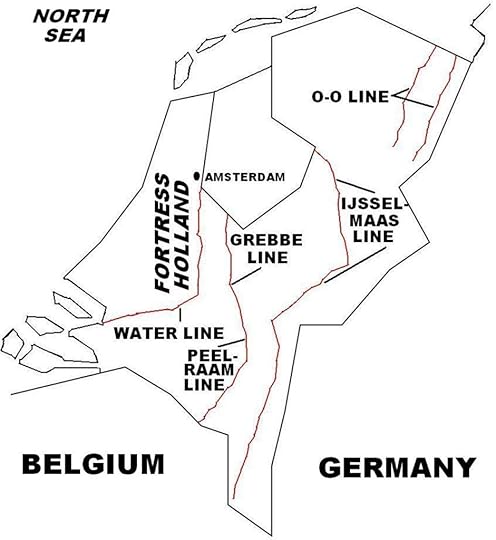

The Netherlands’ defensive positions.

(Taken from Battle of the Netherlands – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background

In February 1940, the German High Command completed the final version of Fall Gelb (English: “Case Yellow”), the invasion of France and Low Countries (previous article), which included the capture of the Netherlands. At various times in the development of Fall Gelb, the Netherlands or only part of it was considered, since the Germans planned that their main thrust would be through Belgium on the way to their final objective, France. However, the Germans (as did the Allies) saw the western part of the Netherlands as the northern end of a battle line if war would break out, and which therefore had to be defended against a potential flanking maneuver by the enemy. For Germany, especially Luftwaffe head Hermann Goering, the air bases in the Netherlands

could be used to launch bombing raids on Britain,

much the same way that the British, if they captured the Netherlands, could use these bases to attack Germany.

In World War I, the Dutch policy of neutrality had been respected by the belligerents, and the Netherlands was not invaded. As a result, with increasing tensions in Europe during the 1930s and even after war broke out in September 1939, the

Dutch continued to hope that their country would be spared the horror and destruction that their neighboring countries had suffered in the Great War. Furthering this hope was that at the start of World War II, the Dutch government immediately announced its neutrality, and the Netherlands was an important trading partner of Germany, and enjoyed warm relations with Britain and France.

The Netherlands was not militarily prepared for war, and only began to upgrade its World War I-era war capability in 1936, belatedly after nearby countries Germany, France, and even Belgium

were already spending large amounts of money on their respective armed forces. With war looming by the late 1930s, the Netherlands had great difficulty purchasing weapons, as deliveries from Germany were deliberately stalled by the Nazi government, and the Allies, particularly France, refused to sell weapons without the Netherlands first joining the Allies. Also, a large portion of the Dutch military budget was directed toward constructing three modern warships for the Netherlands’ commercially important Asian colony, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia).

The Netherlands had insufficient forces and resources to defend the whole country, and so the Dutch military high command devised a plan where, in the event of a German invasion, Dutch forces would fall back to “Fortress Holland” Dutch: Vesting Holland; Figure 9), the western region which was protected by several major rivers: the IJssel on the west, and the Maas, Waal, and Lek on the south. The western region also contained the country’s major cities, including the capital Amsterdam, the seat of government at The Hague, as well as Rotterdam, and Utrecht. Historically, Fortress Holland was defended

by a system called the Holland Water Line, where the waters from these rivers were used to flood the surrounding plains, which slowed or stopped an enemy advance. The Line was later shifted further east and reinforced with forts, and renamed the New Holland Water Line. But by World War I, the whole system was deemed obsolete and powerless against newly developed weapons, such as tanks and planes.

In 1939, the Dutch military established a new defense line east of Fortress Holland called the Grebbe Line (Figure 9), which it designated as its main defensive line where the decisive battle was to take place. In the event the Line was breached, the Dutch Army could still withdraw to the New Holland Water Line to make a last stand. Linked south of the Grebbe Line was the Peel-Raam Line, which was not strongly defended and was decided by the Dutch high command not to be held against a German attack. Further to the east, the Dutch established the IJssel-Maas Line, anchored on the IJssel and Maas rivers, which was manned with frontier units which would sound the alarm of a German crossing across the border. All these defensive lines were reinforced with pillboxes and casemates, which were deemed inadequate even by the Dutch high command.

Despite its neutrality, the Netherlands became increasingly alarmed by a belligerent Germany, particularly with the German conquest of neutral Denmark and Norway. The Dutch government secretly met with military officials of France, Britain, and Belgium to work out a common strategy. Talks

between the Dutch and Belgians faltered, as the two sides had formulated their own defensive strategic lines, and were insistent that the other side extend

their positions to their own lines. In the end, France agreed to fill the gap between the Belgian and Dutch lines by occupying Breda (near the Dutch-Belgian border) and linking its forces with Fortress Holland to the north. As both the Netherlands and Belgium forbid the French Army from entering their territories without first the Germans violating their neutrality, the French High Command assigned their highly mobile motorized and armored units to quickly advance to southeast Holland once the Germans attacked.

France and Britain long wanted the Low Countries to join the Allies, but their repeated prodding was turned down. The Allies feared the possibility that the Netherlands, which was not in the main route of the German invasion through Belgium,

would not strongly resist or would even allow the Germans uncontested passage through Dutch territory on their way to the west. The Allied concern was merited, as the Germans had secretly asked the Dutch government to allow free passage through some Dutch territory, but which the latter refused.

Hitler was fully aware of Dutch unpreparedness for war, and predicted that the Netherlands would fall in 3-5 days. Thus, for the attack on the Netherlands,

the Germans assembled its weakest force, the 18th Army, among all the forces involved in Fall Gelb. German 18th Army consisted of seven weak infantry units. The German High Command realized that 18th Army by itself might be inadequate, and so to add speed and greater firepower to the attack, it added some elite Waffen-SS units, the 9th Panzer Division (which had 140 tanks), and most important, airborne assault units (paratroopers and airborne infantry), which were assigned to seize key sites inside Fortress Holland, and capture Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government at The Hague in order to force Dutch surrender within one day.