More on Zoom and privacy

Zoom needs to clean up its privacy act, which I posted yesterday, hit a nerve. While this blog normally gets about 50 reads a day, by the end of yesterday it got more than 16000. So far this morning (11:15am Pacific), it has close to 8000 new reads. Most of those owe to this posting on Hacker News, which topped the charts all yesterday and has 483 comments so far. If you care about this topic, I suggest reading them.

Also, while this was going down, as a separate matter (with a separate thread on Hacker News), Zoom got busted for leaking personal data to Facebook, and promptly plugged it. Other privacy issues have also come up for Zoom. For example, this one.

But I want to stick to the topic I raised yesterday, which requires more exploration, for example into how one opts out from Zoom “selling” one’s personal data. This morning I finished a pass at that, and here’s what I found.

First, by turning off Privacy Badger on Chrome (my main browser of the moment) I got to see Zoom’s cookie notice on its index page, https://zoom.us/. (I know, I should have done that yesterday, but I didn’t. Today I did, and we proceed.) It said,

To opt out of Zoom making certain portions of your information relating to cookies available to third parties or Zoom’s use of your information in connection with similar advertising technologies or to opt out of retargeting activities which may be considered a “sale” of personal information under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) please click the “Opt-Out” button below.

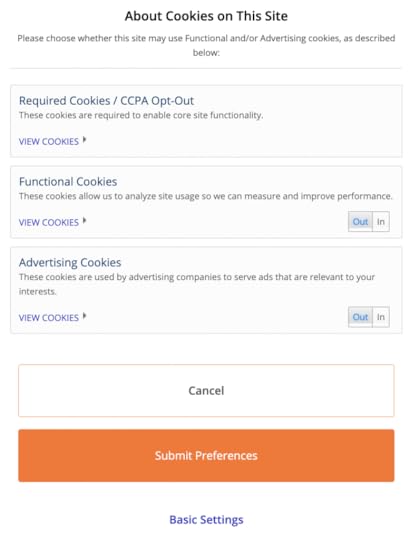

The buttons below said “Accept” (pre-colored a solid blue, to encourage a yes), “Opt-Out” and “More Info.” Clicking “Opt-Out” made the notice disappear, revealing, in the tiny print at the bottom of the page, linked text that says “Do Not Sell My Personal Information.” Clicking on that link took me to the same place I later went by clicking on “More Info”: a pagelet (pop-over) that’s basically an opt-in notice:

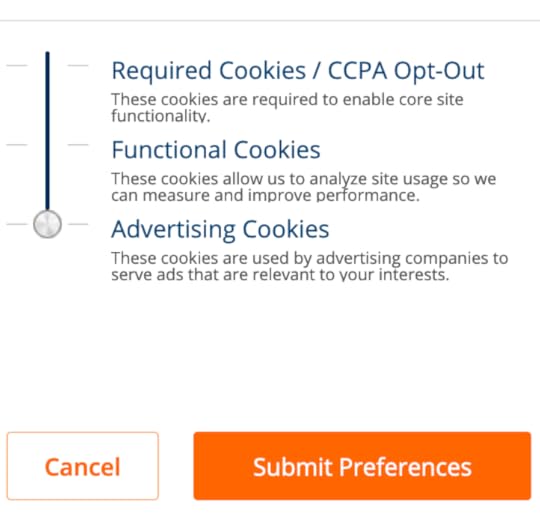

By clicking on that orange button, you’ve opted in… I think. Anyway, I didn’t click it, but instead clicked on a smaller and less noticeable “advanced settings” link off to the right. This took me to a pagelet with this:

The “view cookies” links popped down to reveal 16 CCPA Opt-Out “Required Cookies,” 23 “Functional Cookies,” and 47 “Advertising Cookies.” You can’t separately opt out or in of the “required” ones, but you can do that with the other 70 in the sections below. It’s good, I suppose, that these are defaulted to “Out.” (Or seem to be, at least to me.)

So I hit the “Submit Preferences” button and got this:

All the pagelets say “Powered by TrustArc,” by the way. TrustArc is an off-the-shelf system for giving companies a way (IMHO) to obey the letter of the GDPR while violating its spirit. These systems do that by gathering “consents” to various cookie uses. I’m suppose Zoom is doing all this off a TrustArc API, because one of the cookies it wants to give me (blocked by Privacy Badger before I disabled that) is called “consent.trustarc.com”).

So, what’s going on here?

My guess is that Zoom is doing marketing from the lead-generation playbook, meaning that most of its intentional data collection is actually for its own use in pitching possible customers, or its own advertising on its own site, and not for leaking personal data to other parties.

But that doesn’t mean you’re not exposed, or that Zoom isn’t playing in the tracking-based advertising (aka adtech) fecosystem, and therefore is to some degree in the advertising business.

Seems to me, by the choices laid out above, that any of those third parties (up to 70 of them in my view above) are free to gather and share data about you. Also free to give you “interest based” advertising based on what those companies know about your activities elsewhere.

Alas, there is no way to tell what any of those parties actually do, because nobody has yet designed a way to keep track of, or to audit, any of the countless “consents” you click on or default to as you travel the Web. Also, the only thing keeping those valves closed in your browser are cookies that remember which valves do what (if, in fact, the cookies are set and they actually work).

And that’s only on one browser. If you’re like me, you use a number of browsers, each with its own jar of cookies.

The Zoom app is a different matter, and that’s mostly where you operate on Zoom. I haven’t dug into that one. (Though I did learn, on the ProjectVRM mailing list, that there is an open source Chrome extension, called Zoom Redirector, that will keep your Zoom session in a browser and out of the Zoom app.)

I did, however, dig down into my cookie jar in Chome to find the ones for zoom.us. It wasn’t easy. If you want to leverage my labors there, here’s my crumb trail:

Settings

Site Settings

Cookies and Site Data

See all Cookies and Site Data

Zoom.us (it’s near the bottom of a very long list)

The URL for that end point is this: chrome://settings/cookies/detail?site=zoom.us). (Though dropping that URL into a new window or tab works only some of the time.)

I found 22 cookies in there. Here they are:

_zm_cdn_blocked

_zm_chtaid

_zm_client_tz

_zm_ctaid

_zm_currency

_zm_date_format

_zm_everlogin_type

_zm_ga_trackid

_zm_gdpr_email

_zm_lang

_zm_launcher

_zm_mtk_guid

_zm_page_auth

_zm_ssid

billingChannel

cmapi_cookie_privacy

cmapi_gtm_bl

cred

notice_behavior

notice_gdpr_prefs

notice_preferences

slirequested

zm_aid

zm_cluster

zm_haid

Some have obvious and presumably innocent meanings. Others … can’t tell. Also, these are just Zoom’s cookies. If I acquired cookies from any of those 70 other entities, they’re in different bags in my Chrome cookie jar.

Anyway, my point remains the same: Zoom still doesn’t need any of the advertising stuff—especially since they now (and deservedly) lead their category and are in a sellers’ market for their services. That means now is a good time for them to get serious about privacy.

As for fixing this crazy system of consents and cookies (which was broken when we got it in 1994), the only path forward starts on your side and mine. Not on the sites’ side. What each of us need is our own global way to signal our privacy demands and preferences: a Do Not Track signal, or a set of standardized and easily-read signals that sites and services will actually obey. That way, instead of you consenting to every site’s terms and policies, they consent to yours. Much simpler for everyone. Also much more like what we enjoy here in the physical world, where the fact that someone is wearing clothes is a clear signal that it would be rude to reach inside those clothes to plant a tracking beacon on them—a practice that’s pro forma online.

We can come up with that new system, and some of us are working on exactly that. My own work is with Customer Commons. The first Customer Commons term you can proffer, and sites can agree to, is called #P2B1(beta), better known as #NoStalking. it says this:

By agreeing to #NoStalking, publishers still get to make money with ads (of the kind that have worked since forever and don’t involve tracking), and you know you aren’t being tracked, because you have a simple and sensible record of the agreement in a form both sides can keep and enforce if necessary.

Toward making that happen I’m also involved in an IEEE working group called P7012 – Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms.

If you want to help bring these and similar solutions into the world, talk to me. (I’m first name @ last name dot com.) And if you want to read some background on the fight to turn the advertising fecosystem back into a healthy ecosystem, read here. Thanks.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers