Writing: the Pen or the Keyboard?

Image via Wikipedia

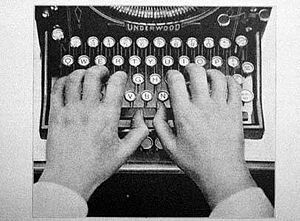

Image via WikipediaWriters are a funny bunch. We each have our own self-imposedrules, routines, favourites and hates. I know of authors who can no more createat the keyboard than they can lay an egg. But my method of composition now dependsutterly on the keyboard. This is despite the fact that I can't touch type anduse only two fingers (not those two!) and a thumb (either will do, I'm notprejudiced). I have to look at the keyboard as I write and then glance at thescreen, with Word's spelling correction thingy open so it underlines any typosI make as I go along. I make a lot of ytops so I really should do somethingabout it. I should learn to touch type, of course. In fact, I spent a fortnight doing just that, about 700 yearsago, on a manual typewriter, and became quite proficient by the end of thecourse. Unfortunately, events jumped up and down on my ambition at the timeand, having finished the course, I never went near a keyboard again for over twoyears. By that time, I'd forgotten everything I'd learned and went back to mythree digit approach. It's not too bad; I can manage about 45 words a minute,when I'm really going. But I'd be much better off if I could touch type. Oneday, perhaps…I don't dare write in script. I was clearly meant to be eithera genius or a doctor, because my handwriting is all but indecipherable, even tome! Where did it all go wrong? The bit about being a genius or a doctor, Imean. As for the handwriting, well I have a small excuse that I was one of thelucky few who, following the end of World War II (I'm not that old that I haveany personal connection with WWI), I was part of the generation who went toschool during the continuing paper shortage. So, I learned to write, at age five,using a framed slate panel and a lead scriber. We complain about Health andSafety rules these days, but at least our kids don't learn using intimatecontact with poisonous metals, eh? I was still in the early days of thisinitial learning when I contracted Scarlet Fever. I recall the ambulance, withits ringing bell (yes, a bell, not a siren) rushing me to the local hospital onChristmas Eve. There, I spent six weeks in an isolation ward, along withumpteen other patients, of all ages and both genders, suffering othercontagious illnesses. Another six weeks off school, after I was discharged,meant I'd fallen seriously behind my fellow pupils when I returned to school afew weeks before my sixth birthday. I never caught up. So, that's my excuse forthe poor handwriting.But, in spite of my dyslexic fingers, the keyboard serves mewell. Thank heavens for the speedy ability to right wrongs there. I repairspelling errors on the fly, but never actually read what I've written until Ireach the end of a piece, no matter whether that piece is a tweet, a shortstory or a novel. Then I return to the beginning and correct, edit, replace andcut wherever necessary. Unlike many writers, I actively enjoy the editingprocess. The creative part, which I do at tearing pace, flying through theparagraphs like a demented racehorse set free from its jockey, I love. Themaking up of lives, events, lands, and all the other story elements feeds thatpart of me where the imagination dwells. In my early days, I did actually write in longhand and thentransposed the work to type on a manual typewriter; a process that took moretime than the composition, usually because I couldn't read my own writing andhad to decipher words to make sense of it. I used the less than perfect Tippexto deal with the odd typo. Later, I progressed to an electronic machine with acorrection ribbon; a real boon. But, in those days before the word processorand computer printer, any re-arrangement of a sentence involved retyping anentire page and, sometimes, an entire chapter. Publishers required pristinetext without alterations, so it could take a long time, much patience, and anentire forest to turn out a manuscript that an agent or editor would accept.Paper wasn't generally recycled back then, so the waste binoverflowed with screwed up pages. These days, we wait until everything appears perfecton the screen before committing the work to paper. But even that isn'tfoolproof: every writer understands that editing on paper is far more likely tothrow up errors than doing the same job on the computer screen. But, at least,it's simpler to correct now, and it isn't often necessary to reprint the entirework simply because of a few errors.So, I compose at the keyboard, correct on screen, print indraft and re-edit using a pen, and then I transfer the changes to the file andreprint in 'best' mode to send my work off to editors and agents. I print, asrequired by the industry, on one side only of the paper, with wide margins. Imean, what's it matter if I still use a forest to achieve this level of perfectpresentation? All that matters is that the reading professional will have no reasonto reject the piece without even bothering to read it. After all, competitionis tough out there. It's good to know that they'll have a pristine piece ofwork to view before they reject it without reading; makes the whole process somuch more worthwhile, don't you think?

A question for you to ponder: Why are you IN a movie, but ON TV?

Published on January 12, 2012 12:00

No comments have been added yet.