Why Go Indie?

The short answer is: I had no choice.

The slightly longer answer: If I hadn’t, you wouldn’t know my novels exist.

But let’s back up a moment. You may be asking yourself not why but “what is indie?” It’s a term that’s also used in music and film. “Indie” means “this artwork is independently produced; it isn’t bankrolled by a large company and isn’t beholden to their demands.” Indie artists are usually a little different; we don’t quite fit the mold demanded of our contracted colleagues.

In my case, “indie” is short for “independent author.” This is our preferred identifier because it signifies that we are professionals. We don’t just slap a first draft on Amazon and expect the adoring public to flock to it. It’s fine to call us self-publishers, but don’t call us vanity publishers. We know our work has worth, but we can also take constructive criticism. We know we can’t do it all by ourselves. We have editors and cover designers. We have printers, but we are our own publishers. We’ve cut out the middle man between ourselves and our readers.

Now, for the why. At the age of fourteen, when I vowed to become a published author, I thought I’d be “traditionally published” by a major press. I thought I’d have a literary agent who’d be like my fairy godmother. I thought the title pages and spines of my novels would say Hachette or St. Martin’s. I thought my novels would be in brick and mortar bookstores. I thought my publisher would send me flowers on my release date, and I’d go on a national book signing tour.

Yes, I really thought like this: I might not have much, but like Cinderella, if I only worked hard enough, eventually my fairy godmother (literary agent) would reward me.

Yes, I really thought like this: I might not have much, but like Cinderella, if I only worked hard enough, eventually my fairy godmother (literary agent) would reward me.None of that has happened or likely ever will. After more than two decades of researching, writing, and revising my Lazare Family Saga project, I spent four years seeking traditional publication for the first book in the series, Necessary Sins. I researched how to query literary agents and which agents were the best fit for my work. I wrote and rewrote my query letter, sent query after query, and pitched to literary agents in person at writing conferences. I’m an introvert, so the latter was particularly terrifying. In all, I approached well over 100 agents. Some editors at publishing houses allow you to query them directly. When my agent well ran dry, I tried that too, submitting to about 15 editors.

I got a few nibbles. My biggest excitement was the enthusiasm of an agent at Writers House, who called my work “masterful.” She imagined she could sell it as a hardcover original. (That’s a big deal and was part of my dream.) She requested a “partial,” the opening chapters of Necessary Sins. The agent then requested the full manuscript, which she received while she was attending a music festival. She related how she frantically searched for WiFi so she could download the rest of my novel and find out what happened next. We had long conversations over the phone.

But neither this interaction nor any other led to a contract. The most frustrating thing about querying is that authors rarely get a why. More than half of the agents and editors I queried didn’t bother to respond, which is typical in the publishing business. Most of the others sent form rejections, the same canned response they send to other hopeful writers, whether those writers followed all their guidelines and were querying a project in the agent/editor’s preferred genre or whether the writer sent gobbledygook. “Not right for our list,” etc. etc. ad infinitum.

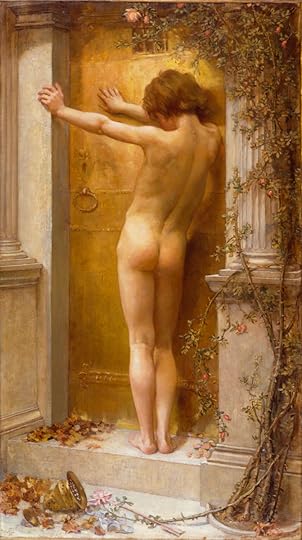

Knock till your knuckles are bloody. The gatekeepers aren’t listening.

Knock till your knuckles are bloody. The gatekeepers aren’t listening.By pitching in person and speaking to other querying writers in my genre, eventually I was able to cobble together a why, which came down to: “Your work is risky. Agents and editors are afraid of risk; they want an easy sell. You are a knee-jerk rejection.” Why is my work risky?

The agents and editors who claim they’re seeking historical fiction really want women’s fiction in a historical setting. Preferably a 20th century setting. In other words, a female protagonist, and she’d better be ahead of her time to make her “relatable.” My protagonist in Necessary Sins is—gasp—a man, and he’s very much a 19th-century man. (Read this blog post to understand my why.) The Publishing Industry knows most readers are women, and it thinks women want to read about women. So the moment an agent/editor/their assistant realized my main character was a man, they rejected my novel. My work is “too long.” Necessary Sins is about 140,000 words, which works out to nearly 500 pages in a paperback. This isn’t really that long, considering I was inspired by epic historical fiction / family sagas from the 1970s and 1980s that are nearly twice that length. But the 21st century is the age of Twitter. The Publishing Industry has decided that readers have short attention spans. They want debut novels of about 80,000 words. Shorter is even better! Longer books cost more to print, so if they fail, the publisher has lost more money. Unless you know someone in publishing and/or you’re a man (preferably both), publishers don’t care if your novel is a meticulously edited masterpiece that really needs to be longer than average. The moment an agent/editor/their assistant realized my book was over 100,000 words (the absolute limit), they rejected my novel.My work is not “own voices.” Many of my point-of-view characters are people of color and I am white. It doesn’t matter how many years of research I’ve done or how nuanced my characters are. It doesn’t matter that the Lazares’ ancestry is mostly white and they are so light-skinned they can “pass.” This is the reason that Writers House agent finally rejected me; I am a marketing problem. At this point, agents/editors/assistants probably reject all queries with characters of color in which the author doesn’t declare her/himself to be “own voices.” Even if I made it past the first two hurdles, this one is insurmountable—at least for an unknown debut author with no connections in publishing.

So after more than two decades of dreaming and labor, after more than three years of pleading at the pearly gates of publishing, I finally had to admit that my work wouldn’t be traditionally published any time in the foreseeable future.

Anna Lea Merritt’s “Love Locked Out” (1890)

Anna Lea Merritt’s “Love Locked Out” (1890)Now for most writers, this would be a temporary setback. They would have another completed project or at least another story idea. This other novel would be more marketable. Then maybe down the line, once they’d acquired an agent and publisher and proved themselves via the success of the other project, the author’s agent might potentially accept the risky project later on.

But I don’t have any other novels. The Lazare Family Saga is my passion project, my labor of love. I have sacrificed everything else in my life for two and a half decades to complete this story. I don’t have the time, energy, or money to do that again, and no other characters are demanding my attention the way the Lazares did. I have a full-time job and health issues. I can’t wait around for a bolt of lightning that may never strike.

If I’d queried for another couple of decades, there is a teeny, tiny chance an agent would have thought my work worth the risks. But then she’d have to find an editor who agreed with her. And that editor would have to convince her publishing house. I have a better chance of being struck by lightning. And the more I learned about traditional publishing, the less keen I was to offer it my soul—and my writing is my soul. This may be partly sour grapes, I admit. But I have heard so many horror stories. There are no fairy godmothers in publishing, but there are a lot of mercenaries who don’t care a fig about authors.

Maya Angelou wrote: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” For me, the agony of an unpublished story is even greater. You’ve done all the work. You’ve forged a completed novel you’re proud of. You believe it’s an important novel, and the people who read it praise it—but that handful of people are the only ones who’ll ever know your novel exists.

Unless you stop clinging to those pearly gates and find another way. Unless you go indie. That is why.

My arms are tired, but I’ll get there!

My arms are tired, but I’ll get there!