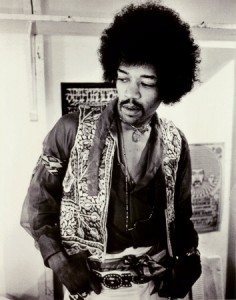

the art of letting your freak flag fly

White collar conservative flashin' down the street, pointing that plastic finger at me. They all assume my kind will drop and die, but I'm gonna wave my freak flag high. — Jimi Hendrix

1

I have multiple small male children, which means I do a lot of Lego (a pox on those Lego pieces that get lost and screw up the design until you find them three days later when you step on them barefoot). If I go to my laptop after a lengthy Lego session, something strange tends to happen: the keys on the keyboard become oddly Lego-like, so that with each touch-tap my brain 'hears' and 'feels' a Lego snapping into place.

Then I read about something called The Tetris Effect (even though I don't play Tetris). From a book called THE HAPPINESS ADVANTAGE:

Tetris is a simple game in which four kinds of shapes fall from the top of the screen, and the player can move or rotate them until they hit bottom. When they create an unbroken line across the screen, the line disappears. The point of the game is to manipulate the falling shapes to create as many unbroken lines as possible.

…In a study at Harvard Medical School's Department of Psychiatry, researchers paid 27 people to play Tetris for multiple hours a day, three days in a row….

For days after the study, some participants literally couldn't stop dreaming about shapes falling from the sky. Others couldn't stop seeing these shapes everywhere, even in their waking hours. Quite simply, they couldn't stop seeing their world as being made up of sequences of Tetris blocks.

It's like the bright spots of light you need to blink away after a camera pops off in your face, or the surreal feeling you sometimes get when you walk out of a movie theatre. In this case it's a cognitive pattern that caused these players to see Tetris shapes everywhere they looked. Playing Tetris had changed the wiring of their brain, laying down new neural pathways that distorted the way they looked at life.

That's the way it is with our brains: They very easily get stuck in patterns of viewing the world, some more beneficial than others…the Tetris Effect…is a metaphor for the way our brains dictate the way we see the world around us.

Gratitude journals, no matter how corny and Oprah-esque you find them, can be surprisingly effective because of their own version of the Tetris Effect. When you routinely scan your days for things that you are grateful for, things that make you feel good, you retrain your brain to start picking up on the positive while letting the negative fade into the background.

2

When you write fiction, you learn to pay attention to the details of your scene. As you develop your craft, you learn to be selective, editing out everything except a few well-chosen details you then present to the reader in order to construct a very specific (if non-existent) reality. Details are small things, but every one of them contributes to a larger whole that makes up the vision, the worldview, expressed through the experience of story.

Your brain is the author of your own, ongoing life narrative. It chooses what it considers the 'relevant' details to bring to your attention – according to the patterns in which it has been trained — while the bulk of incoming stimuli gets edited out from your waking consciousness. Those details form the 'reality' that you navigate everyday, as well as how you interpret it: if the glass is half-full or half-empty.

Not so long ago, I had a conversation with one man about what he thought his 'edge' might be in terms of his natural gift or talent. "I can look at something, anything," he told me, "and see the mistakes and what I need to do to fix them. I can see how to take something and make it better. The flaws just pop out at me, and I can't believe that others don't notice them."

This helps explain why, professionally, this man is extraordinarily successful. His work requires precision and attention to detail or else very expensive things might explode. But now, after reading about the Tetris Effect, I can't help thinking that this might be a reason he's undergoing another divorce. People don't like to be 'fixed', and if you keep pointing out their flaws, they tend to stop wanting to be around you. Not to mention that if your partner's 'flaws' keep popping out at you, you might start asking yourself why you're with this person in the first place.

3

There's a lot of talking and blogging online – including from yours truly — about how in this day and age it's important to Be Remarkable. We have entered The Creativity Age: what matters now is whatever can't be automated, outsourced, or copied by your competitors. Your ability to succeed is tied to your ability to reach people emotionally as well as intellectually, to enlarge their perspective or put an unexpected twist on it, to be relevant, interesting and original. Otherwise you're just another "me too" brand or product or blog, another unread manuscript in the endless Internet slush pile.

But when it comes to actually being Remarkable, or how to go about accomplishing this, often there's silence, a shrug, or a question mark.

For the most part, we don't grow up learning how to Be Remarkable, and the fact that we will take various tests in order to learn what our strengths are indicates that we don't grow up learning ourselves the way that we probably should. That whole question of 'who am I?' gets shuffled behind other pesky questions like 'How will I make rent' or 'will we be tested on this' or 'will I get laid tonight' or even 'are you going to eat that and if not, can I have it?"

We get trapped in patterns of thinking, including the way we've learned to perceive the different aspects of ourselves. We learn what is wrong with us – or rather, what other people perceive as wrong with us. Those external voices get internalized and become the inner voices that we carry around with us until we decide (if we decide) to finally stop listening to them.

What we often don't recognize is that it's the things that we get criticized for, that get declared as the 'weaknesses' that we must fix and fix and fix (until we fail, give up and watch American Idol), that hold the key to our potential Remarkableness. In our weaknesses lie our strengths (and vice versa). If our brains can only learn to perceive them that way.

4

"As young people," writes Parker Palmer,

"we are surrounded by expectations that may have little to do with who we really are, expectations held by people who are not trying to discern our selfhood but to fit us into slots. In families, schools, workplaces, and religious communities, we are trained away from true self toward images of acceptability…our original shape is deformed beyond recognition; and we ourselves, driven by fear, too often betray true self to gain the approval of others."

From kindergarten on, I've always been a freakish reader. I vaulted from picture books to Agatha Christie (my favorite book as a first grader was Ten Little Indians) and my parents, thank their souls, left me alone to read as much as I wanted, whatever I wanted.

Teachers, however, were forever trying to shoo me outside during recess and lunch hour to Play and Be Social. I didn't want to Be Social. I wanted to read. And then, later, I wanted to write.

When I was a 17 year old exchange student in a small country town in Australia, my host parents expressed concern that I was spending so many summer afternoons holed upwith a stack of library books. They fretted that I was an isolate, anti-social, a teenage recluse. They thought I should get out of the house and Be Social. The father advised me to read less (and only nonfiction, because then I would "learn something"). I nodded and smiled and ignored them. They didn't know what to do with me. (When I finally did start partying with some older kids, and breaking curfew, I'm sure they were relieved: "Thank the Lord, she's almost sort of relatively normal!")

I've always been freakishly disorganized and absent-minded ("Justine," one boyfriend asked me during college when I was looking for whatever it was that I'd inevitably misplaced, "how do you get through daily life?" I found it an excellent question). When I was a child, kids teased me because I cried too easily (until I trained myself not to) and because I would sometimes, as they put it, "spazz out" (until I trained myself not to do that, either). I used too many big words and thought too much. I was too intense and melodramatic, given to stalking dramatically out of rooms or hurling my putter when I lost at miniature golf. Later, through my late teens and early twenties, I was too serious, too cerebral (although one guy told me that I smiled too much). Boyfriends who were in taekwondo with me or majoring in English lit with me said I was too competitive. Recently, during a somewhat drunken conversation in a bar in San Francisco, a well-intentioned friend told me that in the time she's known me I've been too melancholy, too much the "tormented writer".

We're allowed to be some things, so long as we're not too much of anything. We prune ourselves back and rein ourselves in, in order to fit in and be normal. And for women, 'normal' often translates into effacing ourselves; we worry that if we speak, we'll be too obnoxious or offensive; if we attend to our own needs instead of those of others, we'll be too selfish. Someone told me that the TEDXWomen conference came into being because of all the women who were turning down invitations to be guest speakers at the original TED. They would defer instead to some man they claimed "knew more" or "was better qualified" to speak on that topic. (Note to all women everywhere: PLEASE STOP DOING THIS.)

And we do this – chip away at our too-ness, become lesser quieter versions of ourselves — because we think that if we follow the rules and fit in, if we can somehow fix ourselves, we'll become balanced and well-rounded. We'll survive and thrive, be loved, find success or, at the very least, some degree of security.

We're kind of deluded that way.

Irony is – today – that the safety found in numbers, in being average and ordinary, is no longer so safe or secure. Management guru Tom Peters argues that "The White Collar Revolution will wipe out indistinct workers and reward the daylights out of those with True Distinction."

By True Distinction, he means those who are too much of something, or do too much of something. Who go to an extreme. Who are decidedly not the norm.

Who are, in some way, freaks.

The good news: we're all freaks. We just need to reclaim those parts of ourselves that we've been hiding away out of shame or embarrassment – for being too this or too that – so we can look at them with a retrained eye, to recognize our strengths and build on them, to become even more of what we are already too much of.

5

My weaknesses, many of which I've already listed, have had a funny way of turning into my strengths. When I took the Strengths Finder test,it identified my top strength as Input:

Driven by your talents, you have been described as someone who reads a lot. You probably carry reading material with you just in case you have to wait in line, eat alone, or sit beside a stranger. Because the printed word feeds your mind, you

frequently generate original plans, programs, designs, or activities. Chances are good that you link your passion for reading to your work. Your definition of "recreational reading" probably differs from that of many people. By nature, you continually expand your sphere of knowledge by reading…Like world travelers, you pick up a variety of souvenirs from your reading, such as facts, data, characters, plots, insights, or tips.

As it turns out, by this point in my life, Input has done well by me. I can't complain about the benefits of my extreme reading, even if, sometimes, people in my life complain that I'm too preoccupied.

Cried too much and oversensitive became empathic and compassionate, two of the traits I value most about my character.

Isolated and anti-social became independent enough to leave my hometown and see the world. I was unafraid of being the new kid, or of being alone in a foreign city where I don't speak the language. I could always learn what I needed to know from a book – and you're never lonely when you're reading a good book.

My episodes of spazzing out as a child turned into what I like to think of as a decent sense of humor: an appreciation of the absurd, the perverse, and the ridiculous.

Too intense? I prefer passionate and spirited. Too dramatic? I have an active imagination that is great for writing fiction. Also for performing. Too cerebral? Oh please. Melancholy? I'm in touch with a wide range of emotions, and the hardwon wisdom they have brought me. Yes, I am ambitious and competitive: would these be bad things in a man? Why should they be in me? I can be selfish, rebellious and bad – I have what my therapist has described as "a bit of a fuck-you spirit" — and I've learned to be grateful for that, otherwise certain life circumstances would have trampled me underfoot.

Disorganized and absent-minded? Well, yes, but I've learned to work around that. I find myself moving toward minimalism and sustainability. As Joshua Becker recently tweeted, "It's better to own less than to organize more." I know enough to stay away from administrative, detail-oriented work; if I ever show up as your personal assistant, you can take it as a sign that the apocalypse is upon us. You should also fire me at once.

6

I'm not one of those people to go on about how we are all perfect just the way we are.

I think we are gloriously and perfectly imperfect.

I think there is beauty, wisdom, strength and vulnerability in our secret fucked-up selves.

But so often the smart thing is not to try to change our natures, but our situation, including those relationships with people who prove toxic to us; we're like plants that differ wildly in their needs for water, light, shadow, soil. It's our job to learn and seek out the conditions we require in order to grow, to blossom, to bloom – hopefully not into the kind of plant that eats people like in that movie LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS.

7

And what I've learned is that if I can change the way I perceive myself, if I can recognize my strengths and weaknesses as flipsides of each other and appreciate them as innate to the experience of being, simply, me; if I can cultivate and celebrate the freak in me, and expect others to do the same (and if they don't or won't, avoid them), then I have to turn that same, retrained gaze on those around me.

I can't be attracted to certain people for certain reasons and then wish that they were, well, different.

It's perhaps one of the biggest tragedies of our nature that we take the people we love and attempt to change them into who we think they should be…because it makes life easier for us, because it suits our agenda, because it makes us feel more comfortable.

If we could only play Tetris in a different sense, if we could only catch the flaws – in ourselves and others – as they fall from the sky, rotate and maneuver them until they form one unbroken line across the screen.

And then disappear.

For further reading check out THE FREAK FACTOR, by David J Rendall. Good book!