Interview with Rebecca Lochlann

I've never yet done an interview on my blog. Mostly because, these past several years, I've been working too hard on my own manuscripts to pay attention to the books being published now. But I recently decided to amend that. I've had the privilege of getting to know quite a few really talented authors, and, consequently, I've had the opportunity to read some really great books. The first of which, was Rebecca Lochlann's The Year-god's Daughter. I loved it so much, I begged her to let me do an interview with her, which she graciously agreed to do.

But first, a little about the book.

Aridela is meant to be a priestess, to save herself for no man, and to become an oracle, dedicating her life to Athene. Only she doesn't want to.

Aridela is meant to be a priestess, to save herself for no man, and to become an oracle, dedicating her life to Athene. Only she doesn't want to.

Iphiboë is a princess, destined to become the next queen, to carry on the royal line, to marry and to sacrifice her husband to the Year-god. Only she doesn't want to.

Aridela's birth heralds a time of change, but those who love her are determined to protect her. In protecting her, are they not defying the Goddess's will? All that they understand and think they know is challenged when the sons of the Mycenaean king come to call, with aspirations for the Cretan throne, and for Aridela. Can they have both? And what happens when their year is up? Will they even survive to be the conquerors they are determined to be? And, of course, there can be only one.

As I was reading the book, I kept saying to myself, "A country where the women rule, where the men sacrifice themselves to love the Queen for one year… What a great story that would make! Oh, wait, that's what I'm reading!" And so, I have to ask, what inspired you write this book?

I had a spark of an idea way back in the late eighties, early nineties. Pure epic fantasy, the kind where the reader is taken to a make-believe world complete with your classic "world-building" aka Tolkien, LeGuin, Alexander, etc. I wanted a female-run country sitting smack dab against a male-run country. That's about as far as my outlining went. I started writing the story (longhand, pencil, notebook pape r—didn't have a computer yet), even drew a map complete with little triangle mountains and winding rivers. At this point I had no more of an idea of Bronze Age Crete than anyone else who has not specifically studied Greek history. I didn't know anything about the "Minoans," and, of course, during the years I was in school, there would never have been a whisper of matriarchal societies, even if such a thing were provable fact. Anyway, there I was, happily writing my fantasy when I happened across the book Moon, Moon, by Anne Kent Rush. It was in those pages that I first learned about the Crete one can find in my story, and it got my curiosity piqued.

r—didn't have a computer yet), even drew a map complete with little triangle mountains and winding rivers. At this point I had no more of an idea of Bronze Age Crete than anyone else who has not specifically studied Greek history. I didn't know anything about the "Minoans," and, of course, during the years I was in school, there would never have been a whisper of matriarchal societies, even if such a thing were provable fact. Anyway, there I was, happily writing my fantasy when I happened across the book Moon, Moon, by Anne Kent Rush. It was in those pages that I first learned about the Crete one can find in my story, and it got my curiosity piqued.

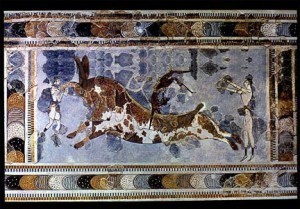

I found out that there actually was a place, in our world, a mere few thousand years ago, where women may well have run things and commanded the respect of nearby male-ruled countries. There are signs pointing to a possible matriarchal setup on Crete, but no one can ever really know for sure about these things. (The Cretans' written records have yet to be deciphered.) This is why I label my genre as "Historical Fantasy," along with "Mythic Fiction."

I don't claim to have some kind of inside knowledge about how this civilization operated or who ruled it, but the more conjectures I read by various authors, historians, and archaeologists, the more I realized, with growing excitement, that I had leeway, the freedom to merge my fantasy story into the history and myths of a real place. This was so much more intriguing than pure fantasy, because this could really have happened this way.

So what kind of research did you have to do? I imagine it took years and years.

The Bronze Age segment of the series took about 15 years of research, since I was starting from scratch. I read and read and read….and read. In those days, it was hard to find books on the subject. They were all out of print and there was no Alibris.com, no Google, not even a Yahoo. The Internet was still in its infancy. I had to scour used bookstores, and the books I found or ordered were often extremely expensive. I sometimes I borrowed books from the library and transcribed the information I needed.

How much of the story is based on researched fact and what is your own invention? Because it's difficult to tell, which I think is a characteristic of an author who knows how to weave their research in without showing it off.

It's all based on researched fact. But many of the archaeological books I read sent my mind on an exploration of new paths. For instance, I realized that just because Arthur Evans coined the term "Minoans," which he borrowed from famous Greek myth, didn't mean that's what the people of Crete called themselves. As I delved deeper, I realized the whole "King Minos" idea was also a later invention, as is so very much of what has come down through history, all very piecemeal, and mostly from a much, much later time. No one really knows where the term "Minos" originally came from or what person it was attached to, but Robert Graves conjectures it was a title held by a female, and the king of Crete had to acquire it through her. Other writers (Jacquetta Hawkes, for one) support this theory. I conceived the idea of "Minos" belonging to a sacred woman on Crete. It made sense that it would belong to a high-ranking woman. I could have taken this in many directions, but I chose to give it to the oracle, the high priestess—not of the royal family, yet just as important as they—maybe more so. I've tried to return life to the older beliefs and myths: those that hang by an unravelling thread on the tapestry of our history.

It's all based on researched fact. But many of the archaeological books I read sent my mind on an exploration of new paths. For instance, I realized that just because Arthur Evans coined the term "Minoans," which he borrowed from famous Greek myth, didn't mean that's what the people of Crete called themselves. As I delved deeper, I realized the whole "King Minos" idea was also a later invention, as is so very much of what has come down through history, all very piecemeal, and mostly from a much, much later time. No one really knows where the term "Minos" originally came from or what person it was attached to, but Robert Graves conjectures it was a title held by a female, and the king of Crete had to acquire it through her. Other writers (Jacquetta Hawkes, for one) support this theory. I conceived the idea of "Minos" belonging to a sacred woman on Crete. It made sense that it would belong to a high-ranking woman. I could have taken this in many directions, but I chose to give it to the oracle, the high priestess—not of the royal family, yet just as important as they—maybe more so. I've tried to return life to the older beliefs and myths: those that hang by an unravelling thread on the tapestry of our history.

I find action scenes really difficult to write. In the labyrinth scene, in particular, there is a sword fight that I found utterly brilliant. How did you come to write it so well? Did you watch sword fights? Do you simply have a very exacting imagination? Or, like other authors I have known, did you reenact a battle scene?

It wasn't always that way, to be honest. I, too, find fight scenes almost impossible. But a friend who read the book before it was published was honest enough to tell me that my fight scenes were lacking. I threw myself wholeheartedly into correcting this problem. I studied fighting scenes in movies, in books, and I made use of my husband's extensive knowledge. Yes, we did enact a few punch-outs. It helped me visualize exactly what could happen. With these assists, I was able to put something together that worked.

You have some very interesting characters. Menoetius, for instance. He's sort of a dark horse. Did you have a purpose in making him disfigured? Was it simply to serve as a disguise, or is there some underlying symbology there?

Ah, Menoetius. He is a classic reluctant hero. But that's where the obvious ends. There is more to him than meets the eye, more than he himself knows at this point. The Year-god's Daughter is as much a "coming of age" story for Menoetius as it is for Aridela. This youth from Mycenae begins life blessed in a way, for he is handsome, and given privileges most children of slaves could never hope to experience. Everything changes later, when he is forced into life without beauty, without status, without hope and from that place…he is honed, transformed.

This is complex plotting, then. Where does that need to tell a complex story come from? Is it from studying literature, or perhaps the huge tomes written in the tradition of epic fantasy?

It just unfolded that way as I was writing. I began with a plan of simple, unrelated stories, but that's not what ended up happening. I just got pulled deeper and deeper into these characters' lives, and through them, into the lives of people as yet unborn. I wanted this ancient story to resonate with modern day people, and future generations.

It strikes me as interesting because I think modern plots are quite simplistic. Perhaps it's why they can so easily be fit into 100,000 word limits. I struggle with word limits, but I don't think it's so much about how many words, as it is about how much of the story to tell. Would you agree with this? And what do you make of the seeming appetite for short, concise, easily digestible books in our digital age? Is there room, do you think, for the classically formed saga?

Gosh I really hope so, but I really don't know. I fear that attention spans are growing shorter by the year, and that there may come a day when no one would pick up a thick book. I hope that doesn't happen. I grew up with big books and from that place, I was shaped as an author. Although I have bowed to the need for books to be shorter, I still am compelled to write a big, epic story, to unravel it like a ball of yarn, to tangle readers up in it so that they can't escape, and hopefully don't want to. I don't necessarily want to write a "historical," a "fantasy," a "romance," or fit myself into other labels. I want to write a story, in the old sense, a tale that draws in readers, sits them in front of a fire, wraps them in a blanket and keeps them there while the world goes by, unnoticed. That is my true goal, and that can't be compressed into a certain word or page count.

You chose to break yours up. How do you feel about that decision now? I chose to keep my first two together, as the division between them is less clear than in those that follow, and because I saw mine as one thick book, but I do get the feeling that readers want to get through books more quickly, whereas I like to linger with the characters longer, to form a relationship with them and to learn something from them, if I can. Breaking a book up into a series is one way around this. Are you happy with your decision to go this route?

If I'd felt I had the freedom to do so, and that it would have been accepted by most readers, I would have put the entire Bronze Age part of my story into one book, as it was originally intended to be. But since it didn't seem like a good idea, I tried to break it up at strategic points, where the reader is hopefully happy with the ending, yet still looking forward to the next segment.

Do you write simply for entertainment's sake, or do you have a higher purpose?

My goal, after writing a story that captures a reader's imagination, is to return this mythical, historical woman/ideal to human awareness, to give her life again, reminiscent of what she enjoyed thousands of years ago.

Do you know your characters before you write them, or do they develop on the page?

Everything revolves around Aridela, and always has. She is the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone, she who is visible from afar, and has profound tasks to accomplish. She is the collective soul of all women, and carries the wounds of every woman within her. Chrysaleon has always been clear as well, but Menoetius is much more complex, mysterious, and difficult. He hides himself: he makes me work at drawing him out, and I'm not completely sure where he will end up in the editing process, frankly.

Do you outline? Or are your stories more organic than that?

I wrote the first several books (which have since been split up,) by the seat of my pants, through inspiration, dreams, and research. When it came to the book containing the series climax, I tried outlining. I liked it. I recommend outlining. It helped me get started, and kept me from going off on tangents.

Now and then, as I read, I found certain themes relevant. Was that your intention, or is it simply that history, and historical themes, repeat themselves through the ages?

It struck me early on in my research how the year-god on Crete was honored then ritually slaughtered, only to rise again in the spring. I saw many beliefs I'd thought of as uniquely Christian, not just on Crete but elsewhere, like ancient Britain, who also utilized a sacrificial king, all long before Jesus came along. There is much to learn about ancient beliefs and religions, and how they relate to present day, and how they actually formed a base for present day beliefs. There is a very ancient theme of sacrifice in this world, resurrection, and godhood and how imperative it is to the well-being of ordinary mortals. Another theme I wanted to highlight was how closely the fertility of the land was intertwined with the fertility of women: not too long before the time period in which my story takes place, the theory was that women could get pregnant from the north wind (Boreas), or from eating beans, or from other solitary endeavors. The man's part was accepted, but wasn't the only way. Some evidence suggests that for thousands of years, women routinely journeyed to temples, where they offered themselves in sexual acts that everyone considered sacred and holy, rather than degrading or promiscuous. Children born to temple maidens were revered. Am I saying this is what happened? No. I'm saying it could have happened, and that's what makes it all so fascinating to me—something worth writing about fictionally—an alternate history that might be real.

It struck me early on in my research how the year-god on Crete was honored then ritually slaughtered, only to rise again in the spring. I saw many beliefs I'd thought of as uniquely Christian, not just on Crete but elsewhere, like ancient Britain, who also utilized a sacrificial king, all long before Jesus came along. There is much to learn about ancient beliefs and religions, and how they relate to present day, and how they actually formed a base for present day beliefs. There is a very ancient theme of sacrifice in this world, resurrection, and godhood and how imperative it is to the well-being of ordinary mortals. Another theme I wanted to highlight was how closely the fertility of the land was intertwined with the fertility of women: not too long before the time period in which my story takes place, the theory was that women could get pregnant from the north wind (Boreas), or from eating beans, or from other solitary endeavors. The man's part was accepted, but wasn't the only way. Some evidence suggests that for thousands of years, women routinely journeyed to temples, where they offered themselves in sexual acts that everyone considered sacred and holy, rather than degrading or promiscuous. Children born to temple maidens were revered. Am I saying this is what happened? No. I'm saying it could have happened, and that's what makes it all so fascinating to me—something worth writing about fictionally—an alternate history that might be real.

It's perhaps strange that I empathised with Iphiboë as much as I did. She reminds me, in some ways of my Imogen. What is her background? Can you tell me more about her?

Iphiboë has a very special reason for the way she is. The name Iphiboë means "Strength of oxen." One might wonder if this name simply doesn't work attached to this seemingly timid girl. But, as with most of the characters in my series, things are not quite as they appear. Iphiboë takes center stage early on in the second book, The Thinara King. More than that I probably should not say.

What is your publishing schedule for the rest of the series?

I hope to have the second book, The Thinara King, out in April, 2012. The third book, In the Moon of Asterion will probably follow it in the fall. Then I take readers into something completely different, yet I promise my heroes will still be there.

You can find The Year-god's Daughter at Amazon 0r Barnes & Noble.com. Learn more about the author at rebeccalochlann.wordpress.com