The Truth of my Story

In September 2018, my teaching mentor asked me to write “the truth of my story.” I’m not completely sure what he meant by that and I remain unsure today. Nonetheless, I wrote my story and I would like to share it here today. I invite your thoughts and comments and I encourage you to write the truth of your own story, whatever that may mean.

The Truth of My Story

I

hate running.

Or,

rather, I don’t feel naturally inclined to running. It’s difficult and time

consuming. I don’t like feeling exhausted or intentionally causing myself pain

and discomfort. Also, it tends to be very boring, especially on a treadmill

when there is no change of scenery. Running doesn’t give me much personal satisfaction

or joy. Yet, in my life I have completed nine marathons, one fifty-mile

ultra-marathon, and countless half-marathons, 5ks, 10 milers, and so on. I have

chosen, despite my natural interests, to run and I have chosen it time and

again.

When

I completed my ultra-marathon after ten hours and thirty-one minutes of effort,

I actually cried I was so tired. They were not tears of joy—they were tears of

sheer exhaustion. I had done all I could to complete the race and by the end I

was too tired to think, to move, to exist. I did not compete against anyone. I

ran alone. I had no decipherable purpose but to accomplish a difficult

endeavor.

I

run not because I enjoy it, I run because I believe it has value. Running

provides me with strength and stamina. Running is challenging. It provides at

least as many mental challenges as it does physical. I run to be a better

soccer player, so that I know before every game that I have provided myself

with the best opportunity to be successful. I run because I believe that it is

the right thing to do. I do not like it. I do not enjoy it. I am not fulfilled

by it. Rather, I am enriched by running.

I

approach writing with much the same attitude. I did not grow up with a joy or

passion for writing or telling stories. I do not now nor have I ever believed

that I am even very good at writing. It is an endeavor—a challenge—a way to

exercise my brain. Writing a novel is not much unlike running a marathon, but

instead of using my legs, I am using my hands, and instead of using my body, I am

using my intellect. I write because I am curious and I desire to learn. I write

because it is an outlet for my restlessness. I write because I am obligated to make

the most of the my time, talents, and opportunities. I write because I believe

it is the right thing to do.

As for the topics I choose to write about, l admit that I seem to have a natural interest in the subjugation, exploitation, and genocide of Western Indigenous peoples. As an undergraduate student in West Virginia, I wrote an essay about the Battle of Point Pleasant which took place October 10, 1774, between members of the Shawnee and Mingo tribes and the settlers, frontiersmen, and militia of western Virginia. While attending graduate school, I wrote my Master’s Thesis on the extinguishment of the Pampas Indians in Argentina and its justification by a group of intellectual elite known as The Generation of 1837. Then, I proceeded to encounter and write about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, an event in Minnesota that resulted in the hanging of thirty-eight Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota and the expulsion from beyond the borders of the state of Minnesota of all Dakota and Ho-Chunk peoples.

Though it is a common theme throughout history, I am struck by the ability of human beings to exploit, hurt, and destroy other human beings. Every time I learn something about a heinous event, I am shocked. I have not come to expect such behavior and I never will. And though many cultures throughout history have experienced suffering at the hands of another culture, I am especially perplexed by the so-called plight of Western Indigenous peoples. One reason, I think, is because of its incredible scope. An entire hemisphere of people were almost completely destroyed.

Another reason is because Indigenous cultures appear to me to be rooted in good, enlightening, and generous ways of living (Though, I understand now that that could be a personal bias developed because of the way Indigenous people and cultures have been depicted by the dominant culture). From what I can tell, most Western Indigenous cultures value kindness and have a deep and profound respect for the earth and all living things. How, I wonder, can such an exquisite and reverent culture be seen as weak and exploitable rather than revered and admirable?

Also,

I am drawn to this history is because it is a part of my own history. For

better or for worse, I live with its legacy. It happened in my own home, right

where I grew up along the Mississippi River just a few miles above the Falls of

St. Anthony.

The final reason I can determine for my keen interest in this history, is because I knew so little about it growing up. I remember learning of Greeks and Romans, of great wars and plagues, of the Gold Rush and the Oregon Trail, but I don’t remember learning anything about treaties and reservations, about Dakota and Ojibwe. I could name all the state capitals, but I could not recite the name of a single Dakota or Ojibwe leader. I could write papers on the Dust Bowl or the American Revolution, but I knew nothing of the exile of an entire people from their homeland, a land which still bears their name—Minnesota, the land where the water reflects the sky/clouds. I did not know Henry Sibley. I did not know Alexander Ramsey. I did not know Sarah Wakefield and the settlers who suffered and died in 1862. I did not know John Other Day and the Dakota who were stripped of their land of culture. And all of them—all of their gain and loss—to pave the way for this rich and abundant land I now call my home.

My

ambition, then, is first as a student. I want to learn the history for myself.

I want to know what happened and why. In doing so, I have determined that this

history—that of discovery, settlement, politics, and culture in Minnesota—is

far more complicated and complex than can be easily understood. To begin, the Indigenous

cultures of this region have a largely unwritten history as well as a culture

that is completely foreign to my own understanding. Additionally, there were

many different people and groups involved in this history, all of them with

different perspectives and motivations. Because of this it is impossible to

fully grasp the how and why of early Minnesota history. But, as an advocate of

learning that does not mean I should not try to discover, interpret, and convey

the history to the best of my ability.

It

is therefore because I am motivated and capable enough to do the work of

reading, researching, writing, and comprehending this history to some degree,

that I feel compelled to share it with those not so inclined, or capable, or

fortunate. I do not expect multitudes of people to seek out and obtain the

wherewithal to delve into the sources of history in the same manner that I

have. Yet, I believe this history is important and necessary. Combining those

factors, I have decided to write stories about Minnesota’s past and its

tarnished history with Native peoples. I want to learn and therefore I desire

to teach.

Humankind

cannot progress without knowledge of its past, no matter how forgettable or flawed

that past may be. Unfortunately, the negative treatment of Native populations throughout

this hemisphere has largely been ignored, misinterpreted, or conveyed through a

narrow perspective. It is only through careful, dedicated research, writing,

and dialogue that this history can be vetted and understood and then utilized

to create a more aware, just society, righting the wrongs of the past and

avoiding the same mistakes in the future.

In the preface for his book, Custer Died For Your Sins, author Vine Deloria, Jr. wrote that the “task of keeping an informed public available to assist the tribes in their efforts to survive is never ending . . . and many additional books on this subject will have to be written correcting misconceptions and calling attitudes to account.” I wish to contribute to this endeavor of calling attitudes to account by using my own personal strengths, skills, experience, motivations, and perspectives. My account may be just one of many, but it adds to the books on this subject written to correct misconceptions and erase misunderstanding and ignorance.

The

truth of my story does not lie within the documents or facts of history. Those

remain unchanged even if their interpretation varies. The truth of my story

lies within me. It is my ability and desire to tell a story that goes beyond the

stories that have already been told. It is my ability to reveal a history that

has been hidden by indifference or stuck in the upper stratus of academia in

multitudes of informational text. The truth of my story lies in the simple fact

that I can, will, and ought to convey an important history in a manner that is

compelling and informative—in a manner that sheds light on a forgotten or

overlooked history and thereby creates awareness and discussion on a painful

and unfortunate part of our past.

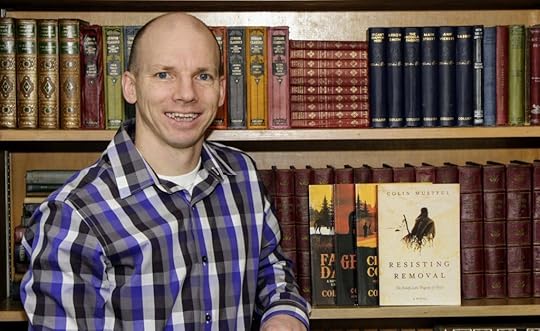

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.