Can We Build Trustable Hardware?

Why Open Hardware on Its Own Doesn’t Solve the Trust Problem

A few years ago, Sean ‘xobs’ Cross and I built an open-source laptop, Novena, from the circuit boards up, and shared our designs with the world. I’m a strong proponent of open hardware, because sharing knowledge is sharing power. One thing we didn’t anticipate was how much the press wanted to frame our open hardware adventure as a more trustable computer. If anything, the process of building Novena made me acutely aware of how little we could trust anything. As we vetted each part for openness and documentation, it became clear that you can’t boot any modern computer without several closed-source firmware blobs running between power-on and the first instruction of your code. Critics on the Internet suggested we should have built our own CPU and SSD if we really wanted to make something we could trust.

I chewed on that suggestion quite a bit. I used to be in the chip business, so the idea of building an open-source SoC from the ground-up wasn’t so crazy. However, the more I thought about it, the more I realized that this, too was short-sighted. In the process of making chips, I’ve also edited masks for chips; chips are surprisingly malleable, even post tape-out. I’ve also spent a decade wrangling supply chains, dealing with fakes, shoddy workmanship, undisclosed part substitutions – there are so many opportunities and motivations to swap out “good” chips for “bad” ones. Even if a factory could push out a perfectly vetted computer, you’ve got couriers, customs officials, and warehouse workers who can tamper the machine before it reaches the user. Finally, with today’s highly integrated e-commerce systems, injecting malicious hardware into the supply chain can be as easy as buying a product, tampering with it, packaging it into its original box and returning it to the seller so that it can be passed on to an unsuspecting victim.

If you want to learn more about tampering with hardware, check out my presentation at Bluehat.il 2019.

Based on these experiences, I’ve concluded that open hardware is precisely as trustworthy as closed hardware. Which is to say, I have no inherent reason to trust either at all. While open hardware has the opportunity to empower users to innovate and embody a more correct and transparent design intent than closed hardware, at the end of the day any hardware of sufficient complexity is not practical to verify, whether open or closed. Even if we published the complete mask set for a modern billion-transistor CPU, this “source code” is meaningless without a practical method to verify an equivalence between the mask set and the chip in your possession down to a near-atomic level without simultaneously destroying the CPU.

So why, then, is it that we feel we can trust open source software more than closed source software? After all, the Linux kernel is pushing over 25 million lines of code, and its list of contributors include corporations not typically associated with words like “privacy” or “trust”.

The key, it turns out, is that software has a mechanism for the near-perfect transfer of trust, allowing users to delegate the hard task of auditing programs to experts, and having that effort be translated to the user’s own copy of the program with mathematical precision. Thanks to this, we don’t have to worry about the “supply chain” for our programs; we don’t have to trust the cloud to trust our software.

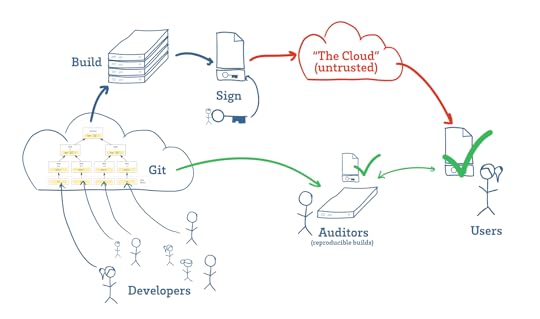

Software developers manage source code using tools such as Git (above, cloud on left), which use Merkle trees to track changes. These hash trees link code to their development history, making it difficult to surreptitiously insert malicious code after it has been reviewed. Builds are then hashed and signed (above, key in the middle-top), and projects that support reproducible builds enable any third-party auditor to download, build, and confirm (above, green check marks) that the program a user is downloading matches the intent of the developers.

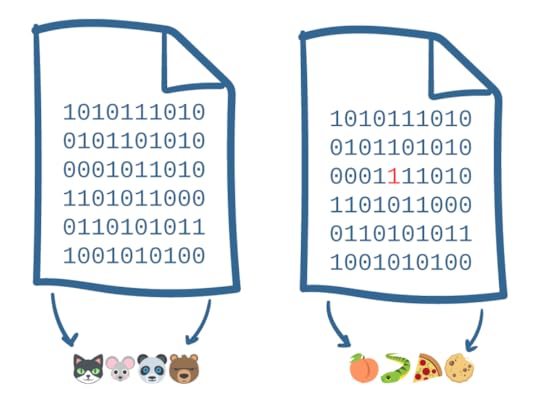

There’s a lot going on in the previous paragraph, but the key take-away is that the trust transfer mechanism in software relies on a thing called a “hash”. If you already know what a hash is, you can skip the next paragraph; otherwise read on.

A hash turns an arbitrarily large file into a much shorter set of symbols: for example, the file on the left is turned into “

Andrew Huang's Blog

- Andrew Huang's profile

- 32 followers