Prophet Or Alarmist?

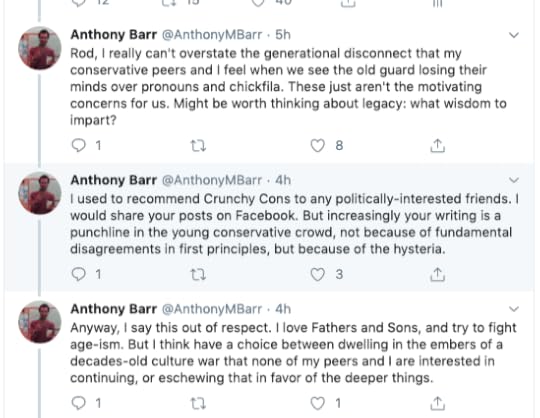

On Twitter today, a recent college graduate said, in response to my tweeting this week:

I accept the criticism — to a point, and in any case I’m glad to be able to talk about this stuff. I laughed a bit when I read it, because not one hour earlier, I had been talking to a friend who owns a small business, and who was complaining about the poor work ethic of younger people. He said he puts in 70 to 80 hours each week trying to make the business succeed, and finds it hard to deal with workers in their twenties who gripe about how worn out they are after 30-hour workweeks. My friend is not quite 40, and he’s already in a “kids these days” mode. I’m 52, and that means I’m old enough to laugh at myself when I was in my twenties, and how much I thought I knew, versus how much I actually knew. And, of course, my dad and I had some good laughs over how “wise” he became as I grew older.

I often reflect on how angry I was at him for refusing to sign off on my applying to Georgetown because he did not want me to go into debt for an undergraduate education. He was a child of the Great Depression, and had a great fear of debt. I thought he was mean, and out of touch with the reality of life today. So I went to LSU, and entered the workforce in 1989 without a penny of debt encumbering me. It took about a decade for me to fully appreciate the kindness that my father had done me by holding the line of accumulating student loan debt. (Had I sought a graduate degree, he probably wouldn’t have objected to me taking out a loan.) That story has never been far from the front of my mind when I think about how rashly a younger me dismissed the wisdom of my father. My dad really was out of touch about a lot of things, but he knew a lot more than I gave him credit for. I bet most of you have a similar story.

On the other hand, honesty compels me to say that there really were some things I understood that the generation ahead of me did not. This is not only the case with my dad, but also in journalism. For example, as my career advanced, it frustrated me how some of my older peers did not grasp that the world had changed. I’m thinking in particular about people — good people, mostly — whose mindset was stuck in an earlier decade, and who didn’t understand things that were much clearer to my generation. Of course nobody who reads history can possibly be under the illusion that the same thing won’t happen to them as they age. All of us are bound to become Grampa Simpson one day. And you know, that’s not always a bad thing. Is there any figure quite as ridiculous as an older person trying to stay relevant to younger people?

Now, to Anthony Barr’s points. I’m not sure how many people Barr speaks for, but I assume that he’s correct about a sizable number of younger people who position themselves on the Right, and who find my writing to be a “punchline” for its “hysteria.” It is true that I often write with alarm about culture war topics, and if you don’t share that alarm, or an interest in these topics, it probably strikes you as paranoid and overwrought. I get it. Maybe my alarm is unjustified.

But here’s the thing: what if he’s wrong? What if I see these things more clearly than he and his co-generationalists do?

It’s interesting that Barr references Turgenev’s novel Fathers And Sons, which is about the generational conflict between a generation of Russian liberals and their nihilistic children. The nihilistic children eventually birthed the Bolsheviks — and we see how well that worked out for Russia. If Barr wants to say that the culture war, as it has been framed since the 1960s, is over, and the left has won, well, he won’t get any serious argument from me.

But that’s not what he’s saying. He’s saying that there are no disagreements in first principles, only in how seriously to take them. He says he prefers to ignore old-school culture-war conflict “in favor of deeper things.” This is confused. It reads like the complaint of someone who doesn’t like my positions, but instead of challenging them philosophically, wants to position my caring so much about them as shallow. This doesn’t make a lot of sense, and here’s why.

When people today say they’re “tired of the culture war,” what they usually mean is that they don’t want to argue about abortion, or, more frequently, they don’t want to argue about LGBT issues. Hey, I understand that! I concede that conservative Christians have lost these battles — LGBT more completely than abortion, certainly, but I will note that even as the numbers of abortions have gone down, support for Roe v. Wade has remained largely unchanged since 1973.

By now, most people understand the stakes in the abortion fight, but I still frequently find that people — among social and religious conservatives, at least — have only a shallow understanding of what’s really at stake on several fronts in the LGBT battle. A lot of this has to do with the fact that the news media’s reporting over the years has been heavily one-sided, advocacy journalism. But it’s also the case that most people just don’t think about these things, and don’t see why they should have to.

Let me send you back to 2006, and Maggie Gallagher’s great Weekly Standard report on religious liberty and same-sex marriage, based on her interviews at a conference of legal scholars who met to discuss this. She began by discussing the decision of Catholic Charities of Boston to withdraw from adoption services after Massachusetts adopted (by court order) gay marriage. As a matter of law, the agency could not refuse then to adopt kids out to gay couples — but as a matter of conscience, it couldn’t do it. So it left the adoption business. Gallagher wrote then:

This March, then, unexpectedly, a mere two years after the introduction of gay marriage in America, a number of latent concerns about the impact of this innovation on religious freedom ceased to be theoretical. How could Adam and Steve’s marriage possibly hurt anyone else? When religious-right leaders prophesy negative consequences from gay marriage, they are often seen as overwrought. The First Amendment, we are told, will protect religious groups from persecution for their views about marriage.

So who is right? Is the fate of Catholic Charities of Boston an aberration or a sign of things to come?

Thirteen years on, it was clearly a sign of things to come. It still is, as religious-liberty cases work their way through the courts. Religious right leaders weren’t overwrought at all. In fact, in the Gallagher piece, there’s a great interview with Chai Feldblum, the law professor and gay rights advocate, who forthrightly concedes — remember, this was 2006 — that yes, there were conflicts everywhere, that gay rights and religious liberty are a zero-sum contest, and that she could not imagine a single instance in which religious liberty should win out over gay rights.

I well remember when that interview came out, because there she was, one of the top gay-rights legal scholars in the country, vindicating what people like Gallagher and me had been saying, amid denunciations for being hysterical. And you know, it made not one bit of difference. We were still denounced as hysterics. Of course we were correct. But one thing many of us didn’t fully appreciate was the extent to which cultural pressure, not state law and policy, would drive the persecution. If you had said to any of us in 2006 that the day would come when LGBT activists could stigmatize a corporation for donating to the Salvation Army, and that that corporation, despite its massive success, would yield to that intimidation, it would have been hard to believe.

Yet here we are. And here we are with people losing their jobs because they will not say that men and women and women are men.

I’m not sure how old Anthony Barr is, but if he graduated college this past spring, that means he was probably around nine years old when Maggie Gallagher published that landmark article. Like everyone his age — it’s not their fault — he has no feel for how swiftly and how radically things have changed since then. The predictions of 2006-vintage “hysterics” have largely come true, and been exceeded by the trans phenomenon. I’ve spoken to religious liberty lawyers and lobbyists who have said that they honestly did not anticipate how fast transgenderism would become a major challenge. After Obergefell, they expected to have a few years before the trans fights ramped up. In fact, it was only a matter of months.

For people of Barr’s generation to say that us old folks are hysterical about these issues is like listening to a middle-aged person say they don’t know why people get so upset about global warming, because as far as they can tell, things aren’t any hotter now than when they were kids. As a matter of fact, I do believe that global warming is happening, and though I find some global warming activists to be, well, hysterical, I have a much higher tolerance for their rhetoric than many conservatives do. Why? Because if they’re right, then we’re foolish to sit back with a “What, me worry?” attitude, and to say that we prefer to focus on “deeper things.”

I have in the past praised the stance of the Dark Mountain movement, which accepts that global warming is happening, but also accepts that at this point, humankind is not capable of making the kinds of radical changes needed to stop it … so the most productive thing to do is to figure out how to adapt. I think traditional Christians are in a similar — not exactly alike, but similar — situation regarding the culture wars around LGBT. We are still in a position when we can win certain First Amendment legal battles, though the purely cultural aspect of the culture war is going to be a much harder slog. There is no reason to give up the resistance, though there is good reason to give up certain forms of resistance. The kinds of battles that right-wing culture warriors were fighting in 2006 are not the kinds of battles that they are, or should be, fighting in 2019. But that’s a different post.

Again, I get it: people of Barr’s generation see many things very differently. But if we’re talking about what Barr terms “the young conservative crowd,” then I would remind them that to be a conservative requires a certain high respect for the wisdom of the past, and a natural skepticism towards moral and cultural innovation. That’s not to say that the past is always right, and that innovation is always wrong. Rather, it’s to say simply that a conservative is not the same thing as a right-wing progressive. Moreover, if being a conservative means anything, it means that when you find yourself not caring about things that motivate the older generations, you should interrogate your own understanding as well as that of the older generation. Progressives assume by definition that newer is better; conservatives ought to take the opposite approach.

Maybe it’s just my generation (Gen X) speaking, but the thing that many of us reacted negatively to about the Boomers is their sense that their generation had discovered the truth about everything, and that we all ought to fall down before their superior wisdom. The narcissism of that generation was off-putting, but it was of a piece with the youth-worship of American culture. To be clear, no generation has a monopoly on truth. Every generation will be wrong about some things, and right about others. I would simply say that as a young conservative, if you find yourself not caring about the same things that older conservatives do, your first move should be to ask if you’ve got that right.

I’m on record in this space complaining that older Reagan-era conservatives are too often stuck in nostalgia for that era’s framing of our problems, and its solutions, and are failing to apply conservative first principles to solving the different problems of our era. I hope that I’ve approached that criticism with some epistemic humility, and I hope that when I and other conservatives of my generation are criticized by younger ones, that we can receive it with epistemic humility. That said, young conservatives should not be lazy about criticizing their elders, and simply assume that because they don’t feel that the things older conservative care about are important, that they are not, in fact, important.

Pro-tip: here are Russell Kirk’s Ten Conservative Principles. If you cannot affirm most of them, then you may not be a conservative after all.

Barr brought up Chick-fil-A and pronouns as an example of Gen X and Boomer-con hysteria. Here, in short, is why young conservatives ought to care about these things.

Religious liberty is important to defend in law. I don’t know Anthony Barr personally, but it sounds from his tweet like he has bought the progressive narrative that says “culture warriors” are only right-wing people. Progressives, especially in the media, assume that anybody who objects to what they want is somehow aggressing against them. In fact, it is they who aggress against us. The reason LGBT issues remain so contested is because progressive activists and litigants keep pushing against us, expanding gay rights at the expense of religious liberty. The main battle lines right now are between religious institutions (e.g., schools) and activists, and professional licensing. As a matter of both law and culture, conservatives — even conservatives who consider themselves pro-LGBT — ought to be defending the right of religious people to be left alone, and to participate in the public square without shame or harassment. Even if you are not personally religious, as a conservative, you ought to recognize the importance of religion to communal life, and defend it, even when you think religious people are wrong. Which brings us to…

Socially conservative beliefs are important to defend in culture. I am a social, religious, and cultural conservative, but I can recognize that if society consisted solely of people like me, it would quickly grow stifling and stagnant. There must be a place for liberals — and unbelievers — to be heard and respected in any healthy society. As a general rule, I am not one for heretic-hunting. Young conservatives who don’t agree with us older ones on LGBT matters ought to still protect our ability to be heard, if only because it’s important for any society to listen to its critics. Besides, do conservatives want to live in an ideologically uniform and monolithic society? I think not. Russell Kirk has said that traditional conservatives “feel affection for the proliferating intricacy of long-established social institutions and modes of life, as distinguished from the narrowing uniformity and deadening egalitarianism of radical systems.” If conservatism means anything, my young friends, it means defending older institutions and modes of life from the narrowing uniformity and deadening egalitarianism prescribed by modern progressivism. For example, you don’t have to like the Latin mass to defend its existence and practice.

Sex and gender matter a lot more than you might think. Earlier today — I think this is what sparked Barr’s tweets — I aired sharp criticism of the leading Southern Baptist pastor J.D. Greear for his policy of “pronoun hospitality.” That is, Greear said that he has decided to call transgender people by the pronouns they prefer, even though as a theological and moral conservative, he doesn’t believe that men become women (and vice versa) only by an act of the will. I agree with Greear that one should not make a point to insult trans people gratuitously, but as I wrote, I think he takes it much farther than he should, and concedes ground that he shouldn’t concede. He’s trying to be polite and pastoral, but in this case, manners is a matter of metaphysics and morals.

Words are unavoidably connected to reality. The word must be grounded in the truth. This is not uniformly the case. In my earlier post, I talked about an older gentleman in my town, who insisted on being addressed as “Colonel,” even though it was probably the case that he had never reached that rank. He was a fabulist, but calling him Colonel was a courtesy that everybody could afford. This is not the case in the matter of trans folk; if it were no big deal, they would not be so insistent on pronoun usage. In fact, they understand better than the merely courteous why words matter so much. Words cannot make a lie true, but words are how we conceptualize reality, and they can either help us see that reality more clearly, or obscure it from our vision. This is why propaganda is so dangerous.

Ultimately, we are talking about metaphysics and anthropology. On the metaphysical point, traditional conservatism has always recognized — philosophically, theologically, or both — that there is a transcendent hierarchy embedded in reality, and that the purpose of philosophizing and theologizing, as well as worshiping, is to draw ourselves into a more harmonious relationship with the things that are. Is human nature given, or is it entirely plastic? Which parts of it are given, and which parts are we free to make over according to our desires?

There is hardly a more profound question. The Soviet system, perhaps the cruelest tyranny that ever existed, was based in part on the idea that there was no such thing as human nature, that what we call “man” is a creature determined by social forces. Change society, and you can mold man into anything you want him to be. At its worst, this led to the horrors of the Romanian experimental concentration camp at Pitesti. Even Solzhenitsyn said this camp was the most barbaric entity in the entire world. The entire purpose of the camp was to destroy the human personality, and to remold it into the perfect communist man.

The point is not that progressives are building Pitesti in America. The point is that at the heart of these issues about sexuality and gender are some core principles about the relationship of the body to the metaphysical order, and what it means to be a human being. If young conservatives like Anthony Barr don’t recognize that, then they are confused about first principles. To give LGBT activists and progressive allies what they want — total affirmation, even beyond legal rights — is to affirm that they are correct about the body, and about human nature. Is this something that conservatives are willing to do?

It should not be something that religious conservatives are willing to do. To be a Christian means that you believe, as the Bible teaches, that man is made in the image of God. This is at the root of human dignity. This necessarily means that human nature is given. It is not created by us; it is created by God, and given to us. We either receive it, or we don’t. As Christians, we cannot believe that we have permission to create ourselves in our own desired image. Gender complementarity is written into the nature of human beings. This is the template of our given reality. And until the day before yesterday, historically speaking, Scripture and Christian tradition have been very clear about the meaning of sexuality. Sex has meaning beyond the sum total of how we feel about it. Sex is not simply expressive; it is a participation in the cosmic order. If that sounds loopy to you, you haven’t thought about it hard enough. As I wrote in the most popular piece I ever did for TAC, an essay called “Sex After Christianity”:

[Cultural critic and sociologist Philip] Rieff, who died in 2006, was an unbeliever, but he understood that religion is the key to understanding any culture. For Rieff, the essence of any and every culture can be identified by what it forbids. Each imposes a series of moral demands on its members, for the sake of serving communal purposes, and helps them cope with these demands. A culture requires a cultus—a sense of sacred order, a cosmology that roots these moral demands within a metaphysical framework.

You don’t behave this way and not that way because it’s good for you; you do so because this moral vision is encoded in the nature of reality. This is the basis of natural-law theory, which has been at the heart of contemporary secular arguments against same-sex marriage (and which have persuaded no one).

Rieff, writing in the 1960s, identified the sexual revolution—though he did not use that term—as a leading indicator of Christianity’s death as a culturally determinative force. In classical Christian culture, he wrote, “the rejection of sexual individualism” was “very near the center of the symbolic that has not held.” He meant that renouncing the sexual autonomy and sensuality of pagan culture was at the core of Christian culture—a culture that, crucially, did not merely renounce but redirected the erotic instinct. That the West was rapidly re-paganizing around sensuality and sexual liberation was a powerful sign of Christianity’s demise.

It is nearly impossible for contemporary Americans to grasp why sex was a central concern of early Christianity. Sarah Ruden, the Yale-trained classics translator, explains the culture into which Christianity appeared in her 2010 book Paul Among The People. Ruden contends that it’s profoundly ignorant to think of the Apostle Paul as a dour proto-Puritan descending upon happy-go-lucky pagan hippies, ordering them to stop having fun.

In fact, Paul’s teachings on sexual purity and marriage were adopted as liberating in the pornographic, sexually exploitive Greco-Roman culture of the time—exploitive especially of slaves and women, whose value to pagan males lay chiefly in their ability to produce children and provide sexual pleasure. Christianity, as articulated by Paul, worked a cultural revolution, restraining and channeling male eros, elevating the status of both women and of the human body, and infusing marriage—and marital sexuality—with love.

Christian marriage, Ruden writes, was “as different from anything before or since as the command to turn the other cheek.” The point is not that Christianity was only, or primarily, about redefining and revaluing sexuality, but that within a Christian anthropology sex takes on a new and different meaning, one that mandated a radical change of behavior and cultural norms. In Christianity, what people do with their sexuality cannot be separated from what the human person is.

It would be absurd to claim that Christian civilization ever achieved a golden age of social harmony and sexual bliss. It is easy to find eras in Christian history when church authorities were obsessed with sexual purity. But as Rieff recognizes, Christianity did establish a way to harness the sexual instinct, embed it within a community, and direct it in positive ways.

What makes our own era different from the past, says Rieff, is that we have ceased to believe in the Christian cultural framework, yet we have made it impossible to believe in any other that does what culture must do: restrain individual passions and channel them creatively toward communal purposes.

Rather, in the modern era, we have inverted the role of culture. Instead of teaching us what we must deprive ourselves of to be civilized, we have a society that tells us we find meaning and purpose in releasing ourselves from the old prohibitions.

How this came to be is a complicated story involving the rise of humanism, the advent of the Enlightenment, and the coming of modernity. As philosopher Charles Taylor writes in his magisterial religious and cultural history A Secular Age, “The entire ethical stance of moderns supposes and follows on from the death of God (and of course, of the meaningful cosmos).” To be modern is to believe in one’s individual desires as the locus of authority and self-definition.

I want to repeat Charles Taylor’s line:

“The entire ethical stance of moderns supposes and follows on from the death of God (and of course, of the meaningful cosmos).”

Can one be a religiously-believing conservative and say that the cosmos lacks meaning? If not, then from what does the cosmos derive meaning? The answer, of course, is from God. But what is God like? If we are made in the image of God, what does that entail? The Bible, and sacred tradition, has answers. You may find the answers unsuitable or boring, or inconvenient for your aspirations to middle-class success in post-Christian America, but the answers are there, and they don’t cease to be truthful because you don’t like them.

About the “hysteria” of people like me regarding these topics, I would point out that from an orthodox Christian point of view, we are living through what C.S. Lewis called “the abolition of man.” A couple of days ago, I was sorting through transcripts of the interviews I’ve done for my upcoming book, and I ran across a startling quote from an older Baptist man in Russia. Talking about the decline of faith in postcommunist Russia, he said that the materialism coming in from the West has done more to destroy religious belief than even the Soviets. Think about that. Geriatric hysterics like me observe the collapse of Christian faith within our civilization, and we see the role that social and cultural change plays in it. Within living memory, the faith has all but disappeared in much of Europe, and we in America are on the same track. I often get comments in this space from people who can’t understand why this bothers me, because according to statistics, people are thriving more today than ever. And everybody is so nice now!

Well, I follow a God who said that it profits a man nothing to gain the whole world, but to lose his soul. If you take Christianity seriously as a description of the Things That Are, as distinct from a mere philosophy of life, or psychologically comforting rituals, then you see the decline and fall of the Christian faith as a civilizational catastrophe with eternal consequences.

Not everybody is a Christian. Not everybody is a conservative. Not everybody is a Christian conservative. But if you do identify as a Christian conservative, and you fail to see how profound this crisis is, then I would say: grow up.

Finally, on the question of being too agitated by the times, let me point you to this interview that journalist Roberto Suro did with PBS for a Frontline documentary a couple of decades ago about John Paul II. Suro covered his papacy for The New York Times and Time magazine. Here’s the relevant segment:

At the end of the day, when you look at this extraordinary life and you see all that he’s accomplished, all the lives he’s touched, the nations whose history he’s changed, the way he’s become such a powerful figure in our culture, in all of modern culture–among believers and not–taking all of that into account, you’re left with one very disturbing and difficult question. On the one hand, the Pope can seem this lonely, pessimistic figure–a man who only sees the dark side of modernity, a man obsessed with the evils of the twentieth century, a man convinced that humankind has lost its way. A man so dark, so despairing, that he loses his audiences. That would make him a tragic figure, certainly.

On the other hand, you have to ask, is he a prophet? Did he come here with a message? Did he see something that many of us are missing? In that case, the tragedy is ours.

You can tell the difference between Pope John Paul II and me pretty easily. He was a great saint; I’m just a middle-aged semi-pious slob who bites his nails. Still, don’t miss the point I’m making. In light of Barr’s comments, consider: What is the difference between a prophet and a hysterical alarmist? How would you know?

The post Prophet Or Alarmist? appeared first on The American Conservative.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 504 followers