Why Create?

Today we take for granted the idea that creativity is a human

attribute. The question “Why Create?” is predicated on the assumption

that we have the option do so. But that assumption has only been around

for about 500 years. Prior to the Renaissance, the notion of individual

creativity didn’t exist, because the concept of individuality as we now

understand it didn’t exist. Paintings, for example, remained unsigned,

and painters, anonymous, because the individual was considered

unimportant. All creative power was vested Above.

On a larger scale, great Gothic cathedrals like Chartres were the

products of thousands of people toiling anonymously in collaborative

efforts that continued over hundreds of years. The great cathedrals were

deliberately designed to give the person who entered them an

overwhelming feeling of insignificance in the presence of an omnipotent

and omniscient Deity.

Individualism Recognized as a Value

A

remarkable shift occurred during the Renaissance, when the power and

potency of the individual began once again to be celebrated, as they had

been in Greek and Roman times. In 1486, the Renaissance scholar and

philosopher Pico della Mirandola offered his Oration on the Dignity of Man,

heralding the shift from the medieval worldview, which disempowered the

individual, to the revolutionary notion that we humans, unlike other

creatures, have been placed at the very center of the universe, and

blessed with powers of free will and creativity that are unlimited and

virtually godlike.

Pico articulated the revolutionary notion that creativity is part of

our expression of free will, part of what makes us uniquely human. He

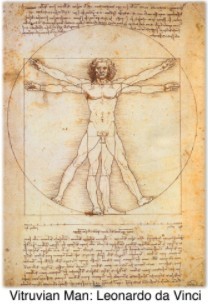

celebrates the notion that we create because we can. Leonardo da Vinci’s

Vitruvian Man (a.k.a. “Canon of Proportion”) and Michelangelo’s “David”

are the best-known symbols of this humanistic rebirth of individual

creativity. But there is one man, Filippo Brunelleschi, who was the

pre-eminent force in the emergence of the new human-centered worldview,

for he both literally and figuratively created a new human-centered

perspective. Just as the Gothic cathedrals had communicated a message

about humanity’s place in the universe, Brunelleschi’s architecture sent

an equally profound but very different message, as best exemplified by

his dome for the Florence cathedral.

Standing beneath Brunelleschi’s heavenly dome, one feels oneself to

be at the center of Creation. One does not feel overpowered and

belittled, but exalted and uplifted in this sacred space. Humankind’s

centrality and importance are also affirmed in Brunelleschi’s invention

of three-dimensional perspective in art; which he taught to Massaccio,

who produced the first Renaissance painting and to Donatello who created

the first Renaissance sculpture. And Brunelleschi exemplified the new

ethos in his own life by registering the world’s first patent for an

invention (his remarkable ox-hoist) – patents being the legal and

economic expression of the value placed on the individual’s intellectual

capital.

Emergence of the Renaissance Man

Although Brunelleschi is the seminal

force, Leonardo da Vinci reigns as the supreme expression of the

“Renaissance Man” or “Uomo Universale” (Universal Man). DaVinci serves

as a global archetype of individual creative possibility. In 1994 Bill

Gates paid $30.8 million dollars for 18 pages of DaVinci’s notebooks.

Why did Gates pay so much? Because he can! And, it’s easy to imagine

that Gates recognizes that his own legacy resides in his role in the

transformation from the Industrial Age to the Information Age; and that

he wanted to associate himself and his brand with the works of a man who

embodies the spirit of the dawn of that earlier new age.

The Renaissance, with its brilliant

artists and architects, sculptors and scholars, taught us anew that

creativity is our birthright, a gateway to our highest expression, the

secret of individuation and personal fulfillment, and the secret of the

art of living. Creativity may also be a means to earning a good living,

as quite a number of artists discovered during the Renaissance. Before

we explore the loftier motivations for creating let’s examine the

relationship between creativity and profit.

The feudal system of the Middle Ages

collapsed because, among other things, of the invention of the

long-range cannon (built by a Hungarian engineer named Urban), which

could blast through the walls of the feudal fortress. As fortress walls

crumbled the printing press, magnetic compass, mechanical clock,

microscope and telescope expanded European horizons exponentially. The

technological breakthroughs that drove the transformation of the Middle

Ages into the Renaissance were all made possible by the funding that

became available as innovative accounting and banking systems evolved.

Brunelleschi, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and all their fellow

geniuses wouldn’t have created much of anything without the Renaissance

equivalent of corporate sponsorship. If the Sforza, Medici and a

succession of Popes hadn’t provided the capital, the Florence cathedral

would’ve remained open to the elements and there would have been no

“Last Supper,” “David” or “School of Athens.” As Professor Lisa Jardine

author of Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance emphasizes,

“…those impulses which today we

disparage as ‘consumerism’ … occupy a respectable place in the

characterization of the new Renaissance mind… A competitive urge to

acquire was a precondition for the growth in production of lavishly

expensive works of art. A painter’s reputation rested on his ability to

arouse commercial interest in his works of art, not on some intrinsic

criteria of intellectual worth.”

Creativity as Vocation

Those of us who “arouse commercial

interest” through our creative endeavor — writers, photographers,

creative directors, web designers, graphic artists, composers, painters

and performers – are part of a great heritage of creating art for cash.

As literary legend Dr. Samuel Johnson put it: “No man but a blockhead

ever wrote, except for money.”

Capitalism provides the most energy and

opportunity for creative expression. And the United States of America —

founded on the remarkable idea that we are all created equal and have an

inalienable right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” — is

the greatest capitalist entity in history thus far. Our nation’s

youthful optimism, diversity and emphasis on freedom and equality

fosters an environment where creativity and innovation are more the

cultural norm than anywhere else. Yet, as we transition out of the

Industrial Age, and face unprecedented environmental, social and global

challenges, the ability to think creatively becomes more urgent and

important.

Historian of science George Sarton

writes: “Since the growth of knowledge is the core of progress, the

history of science ought to be the core of general history. Yet the main

problems of life cannot be solved by men of science alone, or by

artists and humanists: we need the cooperation of them all. “Sarton

concludes that Leonardo’s “outstanding merit” is in his demonstration

that “the pursuit of beauty and the pursuit of truth are not

incompatible.”

For Leonardo, creativity was a function

of the marriage of art and science. He emphasized, for example, that the

ability of the artist to express the beauty of the human form is

predicated on a study of the science of anatomy. But Leonardo’s science

was also based on his art.

Imagination and Creative Thinking Lead to Invention

Leonardo urged his students to awaken the

generative power of imagination in an unprecedented way. Offering “a

new and speculative idea, which although it may seem trivial and almost

laughable, is none the less of great value in quickening the spirit of

invention.” He urged students to contemplate abstract forms – patterns

of smoke, clouds, and swirls of mud – and to allow the imagination to

run freely to discover in these mundane forms “the likeness of divine

landscapes … and an infinity of things.” The Maestro then counsels that

the ideas generated in this flight of the imagination “may then be

reduced to their complete and proper forms.”

In the thousand years before DaVinci in

Europe there was very little encouragement to “quicken the spirit of

invention” by seeking “divine landscapes” or searching for “an infinity

of things.” Before Leonardo the concept of “creativity” as a human

function and an intellectual discipline didn’t exist. Inspired by

Brunelleschi and Alberti, Leonardo effectively invented the modern

discipline of “creative thinking.”

Just as Leonardo helped to invent the art

of creative thinking he also points us toward a compelling reason to

create: to know ourselves and the world around us – to appreciate truth

and beauty — through mirroring the creative source. In his classic work The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination,

Daniel J. Boorstin addresses the mystery of the motivating forces of

creativity. He notes, “the human need to create has transcended the

powers of explanation.” Boorstin adds, “Peoples of ancient Egypt, Greece

and Rome who did not know a Creator-God, who made something from

nothing, still created works unexcelled of their kind. And peoples of

the East who saw a cosmos of cycles created works of rare beauty in all

the arts. Across the world, the urge to create needed no express reason

and conquered all obstacles.” Boorstin summarizes the prologue of his

journey through the history of Heroes of the Imagination,

by proclaiming his intention to “describe the who, when, where, and

what.” But, he concludes, “the why has never ceased to be a mystery.”

Creativity and Immortality

Of course, as Boorstin speculates, “Man’s

power to make the new was the power to outlive himself in his

creations.” In other words, for some, the motivation to create is to

achieve immortality. And, of course, it isn’t necessary to posit or

believe in God in order to create, but as Vincent van Gogh expressed it,

“I can do very well without God in both my life and my painting but I

cannot…do without something which is greater than I, which is my life,

the power to create.”

The Chinese philosopher T’ang Hou

reflects on the nature of the power – the “something greater” referenced

by van Gogh: “Landscape painting is the essence of the shaping powers

of Nature. Thus, through the vicissitudes of yin and yang – weather,

time, and climate – the charm of inexhaustible transformation is

unfailingly visible. If you yourself do not possess that grand wavelike

vastness of mountain and valley within your heart and mind, you will be

unable to capture it with ease in your painting.”

There is a creative force in the universe

that we can all experience in our hearts and minds as a “grand wavelike

vastness.” In creative endeavors we open ourselves to discover our

harmony with “something greater” and, if we persevere, something true

and beautiful just might emerge. As Ansel Adams expresses it, “Sometimes

I do get to places just when God’s ready to have someone click the

shutter.”

So “Why Create?” There are infinite

reasons — to make visible the charm of inexhaustible transformation, to

become more susceptible to grace, to achieve immortality, to know the

mind of God, to manage change, make a living or make a life; but the

simplest is: just because we can.

The post Why Create? appeared first on Michael Gelb.