How to navigate || Part 1: Navigator’s Toolkit + Navigation Mastery

Navigation is one of the most important backpacking skills, and certainly the most liberating. It allows you to drive your own adventure, rather than being a passenger.

As a new backpacker with only rudimentary know-how, I was confined to backcountry thruways like the Appalachian Trail and high-use areas like Rocky Mountain National Park, where I had the security of well worn footpaths, foolproof blazes, and accurate signage.

A pleasant footpath through the green tunnel of the Appalachians

A pleasant footpath through the green tunnel of the AppalachiansAs my navigational competence increased, so too did the adventurousness of my itineraries, best exemplified with high routes and the Alaska-Yukon Expedition. Now, I can essentially wander wherever I please, regardless of whether a trail crew, guidebook writer, cairn-building backpacker, or another person has gone before me.

Adventuring in Gates of the Arctic National Park, which is 3.4 times bigger than Yellowstone and which doesn’t have a single mile of man-made trail.

Adventuring in Gates of the Arctic National Park, which is 3.4 times bigger than Yellowstone and which doesn’t have a single mile of man-made trail.Becoming proficient: The Navigator’s Toolkit

How can you learn to navigate? To become proficient, assemble the proper maps, resources, and equipment, and then develop the skills to interpret and operate them.

Collectively, I’ll call these items as the Navigator’s Toolkit, and in this multi-part series I’ll explain them in-depth.

Part 1: Introduction + my standard kit

Part 2: Maps and resources

Part 3: Equipment

Part 4: Skills

Taking it to the next level: Navigational Mastery

How do you move beyond proficiency, and become a true expert navigator It’s a simple matter of experience.

Of course, experience cannot be purchased, downloaded, or acquired by reading blog posts or taking a class. Instead, you must undertake trips that continually expand your navigational capabilities.

When it’s done well, navigation may seem like a mysterious art form. But, in fact, it’s just pattern recognition — i.e. the application of lessons learned from previous trips onto new scenarios.

Proficient navigators possess the Navigator’s Toolkit. But expert navigators also have a vast collection of past observations to inform their travels through new but similar landscapes.

For example, I can look at maps of areas to which I have never been in Colorado’s Front Range and California’s High Sierra, and predict where you’ll find elk and use trails, talus and tundra, lingering snowfields, safe water crossings, beetle-killed spruce and lodgepole pine, and great campsites. And in Alaska’s Brooks Range I can identify the best line (or, as is often the the case, the least bad) based on the colors and textures of the ground and vegetation.

In contrast, when a merely proficient navigator looks at these same maps or over this same landscape, they don’t have the experience to interpret what they’re seeing. Without past observations informing their options, they often take sub-optimal (and sometimes just bad) lines, as part of their learning process. The next time, they will do better.

By taking a navigation course, watching navigation videos, and reading about navigation, you can more quickly become a proficient navigator. But the only way to become a pro is through practice.

By taking a navigation course, watching navigation videos, and reading about navigation, you can more quickly become a proficient navigator. But the only way to become a pro is through practice.Example toolkit

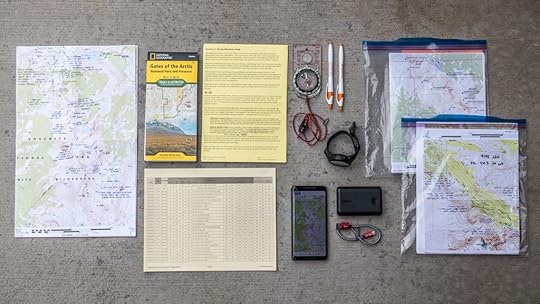

On a normal outing, what’s in my toolkit?

To start, there is the thing between my ears, my brain, which I use to read my maps and resources, and to work with my equipment.

I carry three types of maps:

Paper small-scale overview map, like from National Geographic Trails Illustrated or Tom Harrison;

Paper large-scale detailed maps, normally with the USGS 7.5-minute or FSTopo series as a base map, created in and exported from CalTopo; and,

Digital layers (always maps, and sometimes Landsat imagery) downloaded to my smartphone using GaiaGPS, as backups and/or complements to my printed maps.

For more involved trips, I hope to have several other resources. If I’m following an established trail or route, often they will be publicly or commercially available. For custom itineraries, I may create them myself.

Route description, especially for off-trail sections; and,

Databook, which lists key landmarks, mileage, vertical, and possibly water sources.

To protect and store my paper maps and resources, I bring two gallon-sized freezer bags:

For materials I need right now, stored in a side pocket; and,

For the rest of my materials, stored inside my backpack.

My standard equipment includes a:

Magnetic compass;

GPS watch, which records a breadcrumb track of my route and which gives me time, altitude, cumulative vertical gain and loss, and barometric pressure;

Smartphone with GaiaGPS, which converts my phone into an extremely functional GPS unit with maps;

Portable battery to recharge my smartphone and GPS watch, as well as my inReach; and,

Retractable ballpoint pen (plus a backup), so that I can make notes and draw bearings on my maps.

A complete navigator’s toolkit, less the skills to use these items.

A complete navigator’s toolkit, less the skills to use these items.Leave a comment

How did you learn to navigate?

What questions do you have about my toolkit?

How does your toolkit differ?

The post How to navigate || Part 1: Navigator’s Toolkit + Navigation Mastery appeared first on Andrew Skurka.