what the Grateful Dead can teach creatives about blogging (+ the power of free)

1

Why should you bust your ass on your creative content and give it away, online, for free?

How is this supposed to help you?

And it can't be mediocre stuff, either.

It has to be remarkable, engaging, useful, distinctive…or else no one will care.

2

Part of becoming a powerful artist involves being a relevant artist.

Consistent blogging gives your ideas life and energy as it tosses them to you, dear reader, and you bounce them around and back to the blogger.

The blogger can lean into what works, what resonates, and discard or reshape what doesn't.

I'm not saying that, as a blogger, you learn to pander — which doesn't work all that well anyway, since people respond to authenticity (tricky to define, an easy word to overuse, but we know it when we see it, or at least when we don't).

I'm also not saying that you learn to compromise your vision to fit your (inaccurate) sense of the (ever-shifting) creative marketplace. But ideas evolve through expression and social interaction, and that growth weaves through your creative work.

Creative work requires isolation, but creative insight develops when you're in the world, observing and asking questions and testing your aforementioned ideas and exploring stuff and meeting cool people and taking risks and learning cool shit.

Blogging is a way to be in the world that wouldn't be possible otherwise.

3

Even if the benefits stopped there, I would wonder why more writers in particular, especially literary writers, don't take advantage of this.

"But why should I write," they grumble, "for free?"

Which brings me round to my opening question.

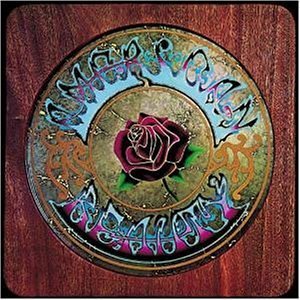

John Perry Barlow* nails it in his introduction to the book EVERYTHING I KNOW ABOUT BUSINESS I LEARNED FROM THE GRATEFUL DEAD (seriously, how could you not want to read a book with this title)?

The band became a massive success without compromising their values or vision in large part because they gave away their music for free. Or rather: they allowed tapers in the audience. As bootleg tapes of their concerts (free content) circulated among fans, they attracted new fans who paid money to come to their concerts (paid content). And because fans knew from listening to the tapes that Grateful Dead concerts changed from night to night they had incentive to attend as many concerts as possible

endowing us eventually with a following so devoted that we could, for a time, fill any stadium in America.

Barlow makes the point that an information economy is "fundamentally different" from a physical economy. In the latter, scarcity equals value. If we can't have it, we want it more. It's why De Beers manipulated the diamond market so that diamonds appeared scarce when they were all over the damn place.

But these rules don't seem to apply to expression

where there appears to be an equally strong relationship between familiarity and value instead.

The worth of a diamond remains the same whether it's hidden in your pocket, displayed in public, or dropped into the ocean like in the movie TITANIC, (which I always thought a stupid pointless move on the point of the heroine, but whatever).

Barlow continues:

…the world's greatest song has no value to anyone but me as long as it's in my head…Only when a lot of people have heard and enjoyed it does it start to accumulate value, and even then not so much for itself but for me as its source. In this, music is more like a service, something that is continuously provided, rather than an object of commerce. The more people who become aware of the quality of that service, the more that can be economically derived from providing real-time access to its provision. Thus, every time we "gave away" a show to the tapers, we increased the value of the music that hadn't been played yet.

It's the free content that draws you in to a much larger story the artist is telling.

The unfolding of that story — that sweeping, creative, singular vision expressed over years through an evolving body of work — is a service rather than an object. The more people become aware of "the high quality of that service", the higher the demand, the higher the perceived value, and the more the artist can charge for access to certain aspects of it (if the artist is inclined in that direction).

Blog posts, in a way, are like songs: little units that have value in and of themselves, fluttering out in all directions, assuming lives of their own –

– if they're good enough to win attention.

Familiarity builds trust and likeability. There's a psychology study in which a girl at college shows up for class everyday — and then, in another class, shows up only some of the time. In both cases, she doesn't speak to anybody, or make eye contact, or linger in any way before fleeing the lecture hall.

But the students who saw her everyday rated her 'likeability' much higher than the students who barely saw her at all.

The more you hear a song, the more you tend to like it (at least until you hate it again for being so overplayed).

When the success of your creative work depends largely on subjective elements — appealing to subjective tastes — it makes sense to attract your right people (through the power of your amazing content) — and make your style as familiar as possible — even before you have anything to sell them.

Because this whole question — are people willing to pay for content? — is, in my mind, kind of ridiculous.

Yes! They are!

It just depends on the story you're telling.

* I met Barlow at a String Cheese Incident concert. It was a highly memorable evening.