I am in Love with Ulysses S. Grant

@font-face { font-family: "Cambria";}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

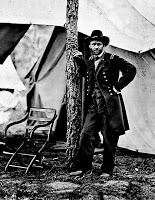

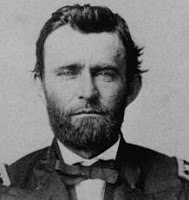

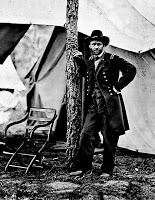

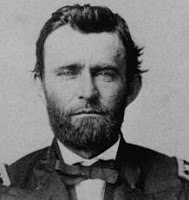

The ManI realize this infatuation may only be a passing fancy, but Ihave begun reading the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. It is a two-volume set, consisting of 552 pages (althoughI'm reading it on a Kindle which results in never having a true feel for whereyou are in a book.) In any event, I've set out on a journey to plumb this man'ssoul. It's nice to have a long read to look forward to.

The ManI realize this infatuation may only be a passing fancy, but Ihave begun reading the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. It is a two-volume set, consisting of 552 pages (althoughI'm reading it on a Kindle which results in never having a true feel for whereyou are in a book.) In any event, I've set out on a journey to plumb this man'ssoul. It's nice to have a long read to look forward to.

Grant wrote these memoirs at the very end of his life, as hewas dying of throat cancer. Seems to me a meaningful vantage point from whichto ponder one's place in history. A man of humble beginnings, Grant hadenormous successes and enormous failures. Some of these would alter the fate ofa nation; others the fate of a people. Some brought him shame and financialruin.

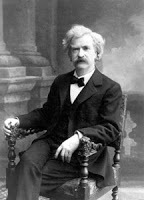

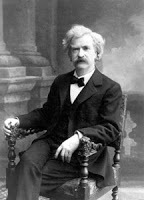

Grant BoosterMark Twain characterized Grant's account as "a great, uniqueand unapproachable literary masterpiece," a war memoir comparable in stature toJulius Caesar's. (There'shyperbole for you, to be expected since Twain was involved in publishing andselling the book.) Fifty years later, holding court underneath her Picasso's,Gertrude Stein claimed Grant's book to be one of the greatest written by anAmerican. Walt Whitman said of Grant, "In all Homer and Shakespeare there is nofortune or personality really more picturesque or rapidly changing, more fullof heroism, pathos, contrast." (I cannot resist also including this quotefrom Whitman, just because it makes me smile: "I do not value literatureas a profession. I feel about literature what Grant did about war. He hatedwar. I hate literature.")

Grant BoosterMark Twain characterized Grant's account as "a great, uniqueand unapproachable literary masterpiece," a war memoir comparable in stature toJulius Caesar's. (There'shyperbole for you, to be expected since Twain was involved in publishing andselling the book.) Fifty years later, holding court underneath her Picasso's,Gertrude Stein claimed Grant's book to be one of the greatest written by anAmerican. Walt Whitman said of Grant, "In all Homer and Shakespeare there is nofortune or personality really more picturesque or rapidly changing, more fullof heroism, pathos, contrast." (I cannot resist also including this quotefrom Whitman, just because it makes me smile: "I do not value literatureas a profession. I feel about literature what Grant did about war. He hatedwar. I hate literature.")

Of course not everyone was a fan of the man. Henry Jamessniffed that Grant's prose was "hard and dry as sandpaper." Matthew Arnold heldthat Grant's use of English was "without charm and without high breeding." But let them say what they like. Dyingand nearly destitute, Grant clung to life and churned out up to fifty pages aday so that profits from the book might provide for his family. He finished themanuscript and died five days later.

A curious man. I am in love with his voice. It wasanti-Victorian, not flowery and verbose but spare, direct, even acerbic. Yet not cynical, at least not by modern standards. The amusement and wit is gentler, forgiving, and always demonstrating a clarity and intelligence that I admire.

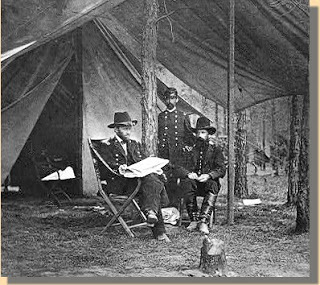

At his best?They say Grant had great courage and coolness under fire. Itcertainly showed during the Battle of Fort Donelson. It was while researching theperformance of Gideon Pillow (perhaps the worst general in the Civil War) in thatbattle that I first ran across Grant's wry recollections. It was no doubt whatset me on a course, six months later, to delve into his memoirs.

At his best?They say Grant had great courage and coolness under fire. Itcertainly showed during the Battle of Fort Donelson. It was while researching theperformance of Gideon Pillow (perhaps the worst general in the Civil War) in thatbattle that I first ran across Grant's wry recollections. It was no doubt whatset me on a course, six months later, to delve into his memoirs.

My question at the moment: how does an aware, intelligentman of his caliber, a great strategist and imperturbable tactician (unruffled by bolting horses or bullets flying overhead), make suchastonishing, bonehead errors of judgment? His presidency was one of the mostcorrupt on record, and some of the worst excesses of the Reconstructionhappened on his watch. He went on to end his life in financial ruin due to laxoversight and further poor judgment. And yet he says this about theMexican-American War (with which I am in complete agreement):

"I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this dayregard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by astronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic followingthe bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in theirdesire to acquire additional territory."

I cannot but believe Grant was a moral man. Moral in, Isuppose, my complex, rather torturous definition of the term. (You have to seeall the complexities, the good and the bad, the dark and the light, and all themurky grey areas in between where things are never clear and people try andfail, and maybe don't try so hard and fail but have to be forgiven anywaybecause, in the end, kindness is the only true religion. And with all this,knowing the tragedies and the pettiness and the failures and the sadness,knowing your own failures and the reefs you've foundered on, you still mostdays attempt the right thing, that which will cause the least suffering and mostwell-being for all. You strive for what your conscience can best live with, because there is, inthe end, no other choice. And if you can do all this without bitterness, witheven a sense of humor, by god, you're a saint.)

(I have not often managed to live up to this definition.)

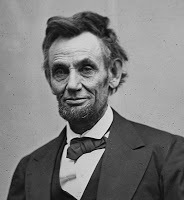

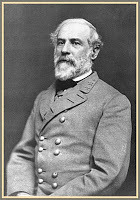

I wish Lincoln had lived to write his autobiography. Hecould be hysterically funny and I'm sure such a book would be a rollicking goodtime (not unlike Benjamin Franklin's autobiography which is a hoot.) I'm also a fan of Robert E Lee and wishhe'd written memoirs so I could hear his voice without all the mythologizingand interpreters, though in his writing Lee is invariably such a gentleman andso circumspect that perhaps little of his inner personality might have shownthrough.

I wish Lincoln had lived to write his autobiography. Hecould be hysterically funny and I'm sure such a book would be a rollicking goodtime (not unlike Benjamin Franklin's autobiography which is a hoot.) I'm also a fan of Robert E Lee and wishhe'd written memoirs so I could hear his voice without all the mythologizingand interpreters, though in his writing Lee is invariably such a gentleman andso circumspect that perhaps little of his inner personality might have shownthrough.

But what is left to posterity, mostly due to a pressing needfor cash, is the account of a man who, as a West Point cadet, just wanted to becomea math professor and who probably would've been happier, when all was said anddone, had that happened. But his soul, his demons, his moral center? Does thearc of the universe indeed bend towards justice, kindness, redemption? Ah,that's why I read. And why I write. To find out.

But what is left to posterity, mostly due to a pressing needfor cash, is the account of a man who, as a West Point cadet, just wanted to becomea math professor and who probably would've been happier, when all was said anddone, had that happened. But his soul, his demons, his moral center? Does thearc of the universe indeed bend towards justice, kindness, redemption? Ah,that's why I read. And why I write. To find out.

The ManI realize this infatuation may only be a passing fancy, but Ihave begun reading the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. It is a two-volume set, consisting of 552 pages (althoughI'm reading it on a Kindle which results in never having a true feel for whereyou are in a book.) In any event, I've set out on a journey to plumb this man'ssoul. It's nice to have a long read to look forward to.

The ManI realize this infatuation may only be a passing fancy, but Ihave begun reading the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. It is a two-volume set, consisting of 552 pages (althoughI'm reading it on a Kindle which results in never having a true feel for whereyou are in a book.) In any event, I've set out on a journey to plumb this man'ssoul. It's nice to have a long read to look forward to. Grant wrote these memoirs at the very end of his life, as hewas dying of throat cancer. Seems to me a meaningful vantage point from whichto ponder one's place in history. A man of humble beginnings, Grant hadenormous successes and enormous failures. Some of these would alter the fate ofa nation; others the fate of a people. Some brought him shame and financialruin.

Grant BoosterMark Twain characterized Grant's account as "a great, uniqueand unapproachable literary masterpiece," a war memoir comparable in stature toJulius Caesar's. (There'shyperbole for you, to be expected since Twain was involved in publishing andselling the book.) Fifty years later, holding court underneath her Picasso's,Gertrude Stein claimed Grant's book to be one of the greatest written by anAmerican. Walt Whitman said of Grant, "In all Homer and Shakespeare there is nofortune or personality really more picturesque or rapidly changing, more fullof heroism, pathos, contrast." (I cannot resist also including this quotefrom Whitman, just because it makes me smile: "I do not value literatureas a profession. I feel about literature what Grant did about war. He hatedwar. I hate literature.")

Grant BoosterMark Twain characterized Grant's account as "a great, uniqueand unapproachable literary masterpiece," a war memoir comparable in stature toJulius Caesar's. (There'shyperbole for you, to be expected since Twain was involved in publishing andselling the book.) Fifty years later, holding court underneath her Picasso's,Gertrude Stein claimed Grant's book to be one of the greatest written by anAmerican. Walt Whitman said of Grant, "In all Homer and Shakespeare there is nofortune or personality really more picturesque or rapidly changing, more fullof heroism, pathos, contrast." (I cannot resist also including this quotefrom Whitman, just because it makes me smile: "I do not value literatureas a profession. I feel about literature what Grant did about war. He hatedwar. I hate literature.")Of course not everyone was a fan of the man. Henry Jamessniffed that Grant's prose was "hard and dry as sandpaper." Matthew Arnold heldthat Grant's use of English was "without charm and without high breeding." But let them say what they like. Dyingand nearly destitute, Grant clung to life and churned out up to fifty pages aday so that profits from the book might provide for his family. He finished themanuscript and died five days later.

A curious man. I am in love with his voice. It wasanti-Victorian, not flowery and verbose but spare, direct, even acerbic. Yet not cynical, at least not by modern standards. The amusement and wit is gentler, forgiving, and always demonstrating a clarity and intelligence that I admire.

At his best?They say Grant had great courage and coolness under fire. Itcertainly showed during the Battle of Fort Donelson. It was while researching theperformance of Gideon Pillow (perhaps the worst general in the Civil War) in thatbattle that I first ran across Grant's wry recollections. It was no doubt whatset me on a course, six months later, to delve into his memoirs.

At his best?They say Grant had great courage and coolness under fire. Itcertainly showed during the Battle of Fort Donelson. It was while researching theperformance of Gideon Pillow (perhaps the worst general in the Civil War) in thatbattle that I first ran across Grant's wry recollections. It was no doubt whatset me on a course, six months later, to delve into his memoirs. My question at the moment: how does an aware, intelligentman of his caliber, a great strategist and imperturbable tactician (unruffled by bolting horses or bullets flying overhead), make suchastonishing, bonehead errors of judgment? His presidency was one of the mostcorrupt on record, and some of the worst excesses of the Reconstructionhappened on his watch. He went on to end his life in financial ruin due to laxoversight and further poor judgment. And yet he says this about theMexican-American War (with which I am in complete agreement):

"I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this dayregard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by astronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic followingthe bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in theirdesire to acquire additional territory."

I cannot but believe Grant was a moral man. Moral in, Isuppose, my complex, rather torturous definition of the term. (You have to seeall the complexities, the good and the bad, the dark and the light, and all themurky grey areas in between where things are never clear and people try andfail, and maybe don't try so hard and fail but have to be forgiven anywaybecause, in the end, kindness is the only true religion. And with all this,knowing the tragedies and the pettiness and the failures and the sadness,knowing your own failures and the reefs you've foundered on, you still mostdays attempt the right thing, that which will cause the least suffering and mostwell-being for all. You strive for what your conscience can best live with, because there is, inthe end, no other choice. And if you can do all this without bitterness, witheven a sense of humor, by god, you're a saint.)

(I have not often managed to live up to this definition.)

I wish Lincoln had lived to write his autobiography. Hecould be hysterically funny and I'm sure such a book would be a rollicking goodtime (not unlike Benjamin Franklin's autobiography which is a hoot.) I'm also a fan of Robert E Lee and wishhe'd written memoirs so I could hear his voice without all the mythologizingand interpreters, though in his writing Lee is invariably such a gentleman andso circumspect that perhaps little of his inner personality might have shownthrough.

I wish Lincoln had lived to write his autobiography. Hecould be hysterically funny and I'm sure such a book would be a rollicking goodtime (not unlike Benjamin Franklin's autobiography which is a hoot.) I'm also a fan of Robert E Lee and wishhe'd written memoirs so I could hear his voice without all the mythologizingand interpreters, though in his writing Lee is invariably such a gentleman andso circumspect that perhaps little of his inner personality might have shownthrough. But what is left to posterity, mostly due to a pressing needfor cash, is the account of a man who, as a West Point cadet, just wanted to becomea math professor and who probably would've been happier, when all was said anddone, had that happened. But his soul, his demons, his moral center? Does thearc of the universe indeed bend towards justice, kindness, redemption? Ah,that's why I read. And why I write. To find out.

But what is left to posterity, mostly due to a pressing needfor cash, is the account of a man who, as a West Point cadet, just wanted to becomea math professor and who probably would've been happier, when all was said anddone, had that happened. But his soul, his demons, his moral center? Does thearc of the universe indeed bend towards justice, kindness, redemption? Ah,that's why I read. And why I write. To find out.

Published on December 07, 2011 20:10

No comments have been added yet.