Venice in interesting times

Visiting May You Live In Interesting Times, the 58th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale, for New Scientist, 16 May 2019

AN ALTERED state of consciousness, realised in virtual reality; a garden full of futuristic plants; avatars steeped in existential despair, a collection of imaginary cameras; a drowning celebrity artist.

All this in just an hour’s quick exploration. Welcome to the Venice Biennale, bursting from its two central venues to sprawl across the city.

The festival has been a fixture for more than 120 years, and has never felt more vital. Its main exhibition this year is called May You Live In Interesting Times. Ralph Rugoff is its curator. He’s more usually found running London’s Hayward Gallery, and he’s brought some of the Hayward’s spirit to bear to Venice. May You Live is colourful, brash, accessible, and full of exciting experiments in technology and digital media.

It’s big, too. Between now and 24 November, half a million people will visit Rugoff’s exhibition, which is spread over two sites. The first is the Central Pavilion of the Giardini della Biennale — gardens laid out along Venice’s eastern edge at the beginning of the 19th century. The second site is a 300 metre-long former rope-making factory in Venice’s Arsenale, a complex of former shipyards and armories.

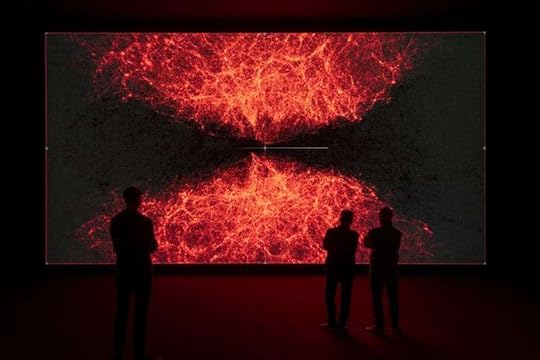

It’s in the Arsenale that you’ll find (indeed, will find it hard to miss) dataverse-1 (lead image) by the Japanese DJ and artist Ryoji Ikeda. Rugoff’s exhibition is big. The Biennale is bigger. But Ikeda, not to be outdone, has gone one better, and created an entire universe on a gigantic, wall-sized high-definition screen.

In a Paris studio that consists of hardly more than a few tables and laptops, Ikeda and his programmers have been peeling open huge data sets, using software they have written themselves. From the flood of numbers issuing from CERN, NASA, the Human Genome Project and other open sources, they have fashioned absurdly detailed abstract animations.

The data itself is what matters to Ikeda — its patterns, rhythms and regularities. What it represents is secondary, even irrelevant. Ikeda’s first love isn’t science, after all: it’s mathematics (and before that, music).

True, dataverse-1‘s 15 minute-long abstract “dances” each explore the universe at a different scale — from the way proteins fold to the pattern of ripples in cosmic background radiation. But Ikeda’s aim is not to illustrate or visualise the universe, but to convey the sheer quantity of data we are now gathering in our effort to understand the world.

In the Arsenale, we are afforded glimpses of this. The Milky Way, reduced to wheeling labels. The human body, taken apart and presented as a sequence of what look like archaeological finds. A brain, colour coded, turned over and over, as if for the inspection of a hyperactive child. A furious blizzard of solar images. And other less easily identified sequences, where the data has peeled away entirely from the thing it represents, and takes on a life of its own: red pixels move upstream through flowing numbers like so many salmon.

Ikeda’s dataverse project, which will take a year and two more productions to reach fruition, is being supported by the watchmakers Audemars Piguet. an increasingly familiar name among artists who operate on the boundaries between art and science. Last year, AP helped Brighton-based art duo Semiconductor with their CERN-inspired kinetic sculpture HALO. Before that, they invited LIDAR artist Davide Quayola to map the Swiss valley where they have their factory.

But while AP has a declared interest in art that pushes technological boundaries, Ikeda himself fights shy of any talk of technology, or even physics. He’s interested in the beauty of number itself.

In an interview with the Japanese curator Akira Asada in 2009, he remarked: “I cannot help but wonder if there are any artists today that give real consideration to beauty. To me, it is mathematicians, not artists, who epitomize that kind of individual. There is such a freeness to their thinking that it is almost embarrassing to me.”

Other highlights at the Arsenale include Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s Endodrome, (above) a purely virtual work, accessed through a HTC Vive Pro headset. The artist envisioned it “as a kind of organic and mental space, a slightly altered state of consciousness”. Manifesting at first as a sort of hyper-intuitive painting app, in which you use your own outpoured breath as a brush, Endodrome’s imagery becomes ever more precise and surreal. In a show that bristles with anxiety, Gonzalez-Foerster offers the festival-goer an oasis of creative contemplation.

Also at the Arsenale, and fresh from her show Power Plants at London’s Serpentine Gallery, the German artist Hito Steyerl presents This Is the Future, (above) a lush, AI-generated garden of the future, all the more tantalising for the fact that you’ll probably die there. Indeed, this being the future, you’re sure to die there. Steyerl mixes up time and risk, hope and fear, in a wonderfully sly send-up of professional future-gazing.

The Giardini, along the city’s eastern edge, are the traditional site of La Biennale Art Exhibitions since they began in 1895. They’re where you’ll find the national pavilions. Hungary possesses one of the 29 permanent structures here, and this year it’s full of imaginary cameras. They’re the work of cartoonist-turned media artist Tamás Waliczky. Some of his Imaginary Cameras and Other Optical Devices (above) are based on real cameras, others on long-forgotten 19th-century machines; still others are entirely fictional (not to mention impossible). Can you tell the difference? In any event, this understated show does a fine job of reminding us that we see the world in many, highly selective ways.

There’s quite as much activity outside the official venues of the Biennale as within them. At the Ca’ Rezzonico palazzo until 6 July, you have a chance to save an internationally celebrated artist from drowning (or not- it’s really up to you). A meticulously rendered volumetric avatar of Marina Abramović beckons from within a glass tank that is slowly filling with water, in a bid to draw attention to rising sea levels in a city which is famously sinking. Don’t knock Rising (above) till you’ve tried it: this ludicrous-sounding jape proved oddly moving.

Back at the Arsenale, Ed Atkins reprises his installation Olde Food, (above) which had its UK outing at London’s Cabinet gallery last year. Atkins has spent much of his career exploring what roboticist Masahiro Mori’s famously dubbed the “uncanny valley” — the gap that is supposed to separate real people from their human-like creations. Mori’s assumption was that the closer our inventions came to resembling us, the creepier they would become.

Using commercially purchased avatars which he animates using facial recognition software, Atkins has created his share of creepy art zombies. In Olde Food, though, he introduces a new element: an almost unbearably intense compassion.

Atkins has created a world populated by uncanny digital avatars who (when they’re not falling from the sky into sandwiches — you’ll have to trust me when I say this does make a sort of sense) quite clearly yearn for the impress of genuine humanity. These near-people pray. They play piano (or try to). They weep. They’re ugly. They’re uncoordinated. They’re quite hopeless, really. I do wish I could have done something for them.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers