Performing Herman Cain

Performing Herman Cain

by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

I'vetaken as much interest in Herman Cain's now suspended campaign for president,as I might have over whetherindividuals choose to use mustard or mayonnaise on their ham sandwiches. Beyond simple curiosities about why somepotential voters found Cain appealing, I've had little desire to find out whatanimates Cain's political concerns. This is not to say that I didn't share the belief among someAfrican-Americans, that Cain was some index of the ultimate limits of post-racediscourses—themselves a victory for multiculturalism, as opposed to a victoryover anti-Black racism, as Vijay Prashad has describedit. Yet, Cain's candidacy has beenshrouded in so much absurdity, that it's hard to see him as anything other thana performance artist.

Forall the talk that necessarily questions Cain's commitment to a Black politicalproject and wrongly questions his "blackness," as if Black identity can besimply reduced to a content analysis, Herman Cain's "performance" is filledwith enough racialized signifiers, that his oft willingness to break out insong is far more interesting than even the sexual dramas (some potentiallycriminal and others simply morally questionable) that have all but ended hisquest for the Republican nomination for President.

Itwas during a recent dinner conversation with two colleages, Guthrie Ramsey, Jr.and Angela Ards, neither of whom who had spent much time watching Cain, thatthe performative aspects of Cain's public presence came into focus for me. Both Ramsey and Ards have expressedrelative shock over Cain's clearly "raced" diction; if Herman Cain had once called you on a cold sales call some thirtyyears ago, there would be little to suggest that he wasn't a Black man from theSouth.

Indeed,the way that Ramsey and Ards described recoiling at the sound of Cain's voice (asopposed his "twirling in my head" moment) was reminiscent of some of thestruggles faced by New York Governor Alfred Smith more than eighty-years ago,when running for President. Potential voters outside of the Northeast,similarly recoiled in response to Smith's decidedly "New Yawk" accent,particular in an era well before television became such a vital component ofnational politics.

Theirony is that only four years ago, then Senator Barack Obama would have neverbeen taken seriously as a presidential candidate had he sounded like Cain orany number of Southern Black men—something the President's current runningmate, noted at the time.

BothObama and Cain's vocal performances are reminders of the role that the voice has played in establishing the"authenticity" of Blackness. One hundred years ago when Black "black-faced"minstrels were in open competition with White "black-faced" minstrels over whowere the real "darkies," the tippingpoint occurred with the development of the phonograph and the "talkies" (motionpictures with sound), and the ability of Black artists—most prominently BertWilliams—to approximate Blackness insound (as opposed to the use of black vernacular language) in ways thatwere more challenging for White "black-faced" minstrels; Al Jolson simplysounded like he was trying to sound Black.

Despitehis "sound of Blackness" Cain had been successful reaching a broader audiencethan expected, in large part of his deft negotiation of racial nostalgia andracial accommodation—none which makes him any less Black or so-calledself-hating, but simply more willing to work within the constraints of a highlyracialized society, on that society'sterms. It goes without saying,perhaps, that Cain is a racial throwback.

Theoft-cited example of Cain's experiences at Morehouse College in the 1960s,where his father insisted that he "stay out of trouble," in an era when Blackcollege students were indeed starting trouble and changing the world for thebetter—even at an institution known today for its marked socialconservatism. This admission onCain's part, no doubt strikes a chord for potential voters who still readPresident Obama as postmodern Black Power radical, as embodied in the frankracial talk of his life partner Michele Obama during the throes of the 2008primary season.

Thatbit of autobiographical positioning on Cain's part was easy; moredeliberate—and complicated—has been his performance of spirituals, at anynumber on campaign events. Hiswillingness to take on the role of the minstrel—the American brand of travelingbards who traveled the country, telling stories of far away lands, and not tobe mistaken with the "black-faced" variety, who traveled the land embodying"the other" in Blackness—has in some way been a stroke of performative genius,no matter how uncomfortable it makes the Black rank-and-file feel.

Thesongs are a gesture towards nostalgia, a way to make some Whites morecomfortable with Cain, and clearly not a performance for simply performance sake; Cain has clearly been singing these songs all of his lifeand sounds pleasing doing so. Quiet as it's kept, Cain's gestures were every bit as effective as thePresident's "dirt off my shoulder" gesture, which quickly became part of themythical lore that has characterized Candidate Barack Obama.

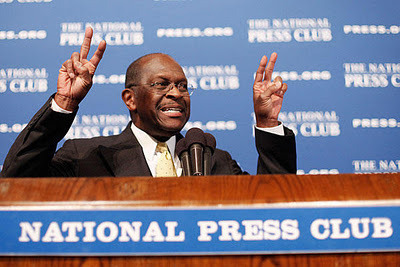

Forexample, when Cain broke out into a version of "He Looked Beyond My Faults(Amazing Grace)," at the National Press Club, to a melody most recognizable asthe Irish ballad "Danny Boy," few knew that there was a version of "AmazingGrace" that was set to "Londonberry Air," an Irish song that dates back to thelate 18th century. "Londonberry Air" later served as the melody for Frederick Weatherley's"Danny Boy," which the late Dottie Rambo later appropriated for her 1970southern gospel classic "He Looked Beyond My Faults".

ThatRambo worked closely with well-known televangelists like Oral Roberts, JohnHagee, Jim Bakker, Paula White, Pat Robertson and T.D. Jakes, speaks volumesabout the audiences that Cain was trying to reach with his gestures. As much as positioning himself at the anti-BarackObama—which can't be easily conflated as "anti-Black"—Cain shrewdly, via hisuse of Southern gospel, positioned himself as the true southern conservative.

Inmany ways, it is not surprising that what has undone Cain's campaign is not hisshuffle back to Dixie routine—which none of his Republican peers could haveever pulled off credibly—but thebasic truism that as an African-American candidate you simply have to be abovethe moral fray.

Unfortunately for Cain there is no nostalgic era thathe can conjure to help navigate the still-water mess that continues to be raceand sex, unless he starts singing R Kelly's "Bump N' Grind" at future publicappearances.

***

MarkAnthony Neal is the author of five books including the forthcoming Looking for Leroy: (Il)Legible BlackMasculinities (New York University Press) and Professor of African &African-American Studies at Duke University. He is founder and managingeditor of NewBlackMan and host of the weekly webcast Leftof Black . Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan .

Published on December 03, 2011 12:05

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.