SOMETHING about the planes. They draw him in. Perhaps it’s the...

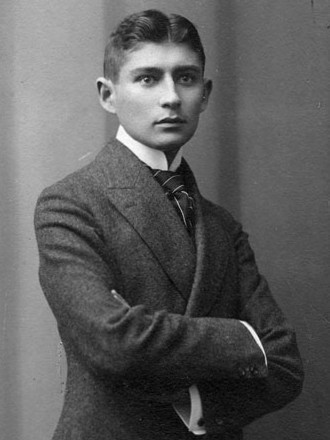

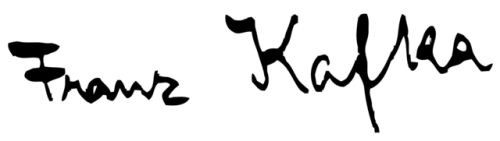

SOMETHING about the planes. They draw him in. Perhaps it’s the drama, the epic struggle of the airmen fighting to get their machines off the ground. It gives him hope when it comes to his writing. Yet, leave the excitement of this air show in 1909 behind and fast forward to his deathbed decades later, in 1924, when he is editing ‘The Hunger Artist’. The joy of ‘The Aeroplanes at Brescia’ is gone. Instead, Franz Kafka gives us the story of a man nobody believes, a man unable to escape suspicion no matter his sincerity, a hero grounded and made subject to the merciless, never-ending gaze of onlookers, who dies miserably in a cage. The metamorphosis is complete.

What happened to him? The mysterious menace that pervades Kafka’s work clouds our understanding of his life. We are tempted to believe he was miserable, dying at the relatively young age of 40. He starves to death. He has a form of tuberculosis that seals his throat. His three sisters Ellie, Valli, and Ottla are murdered during the Holocaust by the Nazis. Had he survived he too might have met the gas chamber.

But just as his novels are left incomplete, so too Kafka’s life story. More manuscripts, more diaries, more pieces of correspondence are destined to emerge. For decades they have been subject to a legal battle, scattered in bank vaults and safes in Israel and Switzerland thanks to Max Brod’s secretary Esther Hoffe. Yet, even if Kafka the man is yet to fully come out, some readers can already sense what town knows. Here is a writer deeply concerned with the oppressive power of the deep state; who fears autocrats as much as he fears fathers; who exudes queer sexual desire but must hide it. This is the world in which Anu Lakhan’s new chapbook Letters to K, complete with drawings by Kevin Bhall, arrives.

— from ’Reading Kafka in Port of Spain’, my review of Anu Lakhan’s Letters to K.