“You Can Only Listen To A Live Album Once”

“One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.” –Jack Kerouac

In 1975, I walked away from a free ride in college to be a professional musician. I moved back to KC from New York, got married, and started to wedge my way into the local music scene. In those days, a guy could make a living playing six-night-a-week gigs around the metro area; you just had to figure a way to break in to the clique of players who had the jobs.

Your dues got paid in local jam sessions until somebody picked you up for a gig. By 1977, the only successful “wedging” I’d done into the business had landed me a modest schedule of students at a strip mall music store and a guitar player’s chair in a dart-board-band hired out by a local agent. (You called them dart-board-bands because you’d get these one-nighters where you’d swear the agent had found the gig by throwing a dart at a map of the local region.)

The other challenge that had grown and festered had everything to do with my musical skills. In retrospect, ‘paltry’ is the most charitable description of my playing. I could cop most records… kinda… but copying guitar licks from disco hits didn’t feed the musical aspirations that took me out of school. Luckily, I hooked up with a teacher in the spring of ’77 and I ended up studying with him for the next 17 years.

“People copy me so much. I even hear them play my mistakes better than me.” –Jimi Hendrix

John Elliott was a KC legend of sorts. When friends heard I’d gotten on his waiting list they’d always tell me to stick with it if I got on with him. “John Elliott taught Pat Metheny!” That’s what they said. Later, when I asked him about it, he assured me that he had only helped Pat. John said: “I helped as best I could, Pat DIDN’T need a teacher.” Funniest thing about John and the Metheny legend… and the line of guitar players on his waiting list because of it… he didn’t play guitar. John played piano, composed, and arranged big band charts. He’d been the music director for the Playboy Club. Sexist anachronism that it was even then, music director for the Playboy Club was a big deal if not THE biggest deal for a residency gig in KC.

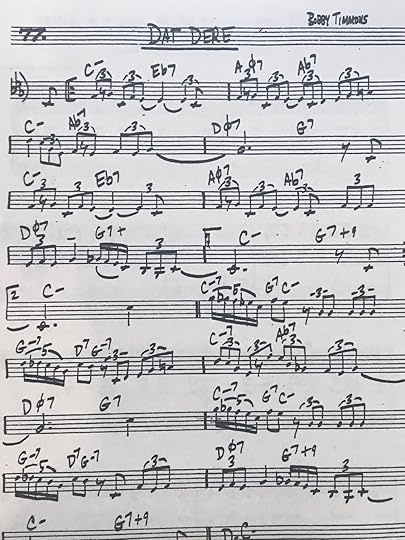

Musical goals for John appeared deceptively simple. He showed me a lead sheet one day and said: “You’re trying to learn how to read and play this solo. You need to know how to improvise a solo over this lead sheet, or any lead sheet, solo… by yourself. If you can’t ‘realize’ a tune in all of its creative potential by yourself, other players, the ones that can really blow, ain’t gonna be that interested in playing with you.”

I kept our weekly appointments. I diligently internalized all of the theoretical components of his instruction as best I could. Finally, after several months of digesting his framework, we’d begun to work with the harmonic structures of actual tunes. At the end of one of my lessons, he started comping a blues in C and nodded at me to take a few choruses. Playing blues had been my entry into this whole music thang, so I felt unshackled to let him see what I could do. Halfway through the second chorus, he started doubling my lines with me as I played them. He continued to shadow my solo through the next chorus deviating only when particular quirks in my chops surfaced. He continued to come close to doubling my lines through the next chorus and then we stopped for the lesson. He didn’t have much to say except: “See you next week.”

Several weeks passed and, finally, I had to talk to him about my ‘solo’ and several other confusing realities that had surfaced because of what he had me listening to on the side. I’d learned to play for the most part by shedding along with BB King records; spent a lot of time with one album: LA Midnight because I could tune my guitar to one song where BB called out the key. It’s not that John didn’t like BB King, but he had insisted that I listen to other players to get a sense of where we were going. I had slowly accumulated a collection of LPs by the usual suspects: Kenny Burrell, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis. John had a special affection for Joe Pass because of some duo albums with Ella, but the hands-down-you-better-listen-to-this-guy-until-you-get-it player was Jim Hall.

When you are a refugee from Electric Ladyland, Jim Hall can sound a bit understated, to say the least, but listen I did. I wore out one particular live album, a trio recording, that I initially heard with bored ears. But, over time, as I reapplied myself to listening with each drop of the needle to the turntable, it turned into a spectacular display of musicianship and understated technique.

Finally, I got the courage to ask what he had thought of my soloing. “Hey, I was wondering.” Like the thought had just spontaneously surfaced. “How was my solo when we played together a few weeks ago?”

He sat at the piano finishing some notations for my lesson: “Oh, I didn’t think to listen that way.” As he continued writing, “I was just trying to assess if you had any lyrical skills with solo melodies.” He turned with a kind smile. “You had enough ah…inoffensivenese. We have something to work with AND we have a lot of work to do.”

“How were you copping my lines with me in real time? I didn’t know what I was gonna play until I started.”

Now he had a big smile. “As predictable as you were, I would have assumed that you’d played those lines a thousand times.”

“Ha ha.” I gave a mock laugh as I remembered the roadblock of the same-licks-a-thousand-times that had brought me to him.

He put down his pencil and turned to me. “Let me give you a big picture lesson today. First thing, let’s look at these labels that you got all over your music: rock, blues, country, jazz, fusion, classical… whatever. I’m giving you the only two labels you need today: there’s good music and there’s bad music. Yeah, it’s a matter of taste, but most people don’t have good taste in music. The only ‘taste’ they have is the one they’ve been told to like.”

“I’m hip to what you’re saying about the audience in general. But there is music called jazz, or blues… or whatever.”

“In your world, any label you put on the music is a marketing term. Before recordings, the only label, well… those labels didn’t exist before recordings. The context dictated the musical expression. If you’re in the backwoods of 19th Century Missouri, you ain’t listening to baroque music on a pipe organ. You’re noodling out shit on a banjo to rattle your inner muse.”

He looked at me and paused for thought, then continued. “The road you’ve begun to walk down is most easily described as jazz at this point in musical history. But a bigger view is: you’re not trying to be a jazz musician. You want to be an IMPROVISING musician. The other option as a player is to become an interpretive player…what you think of as a highly skilled classical musician. In this huge world of musical phenomena, the most highly skilled interpretive players are in the classical arena. A case could be made that some stone-cold studio players bring an equal level of interpretive skill to the table, but the material doesn’t rise to the challenge of the classical repertoire.

“The best improvisers are in the jazz arena.” He looked at me just begging for a retort. I continued to listen. “I sometimes get these rock dogs that want to argue about it. They seem bound and determined to prove that you can make a sow’s ear out of a silk purse.”

The opening for my Jim Hall question had surfaced: “I’ve been wearing my stylus out listening to albums you recommend. That Jim Hall Trio thing he did in… ah, Toronto, I think. I listen to it over and over. I’ve noticed something: I have quite a few moments on the two sides where I anticipate hearing again a ‘good part’. There’s a run on the last solo chorus for Angel Eyes that I especially focus on. It took a couple of weeks and a hundred plays to hear it. I wouldn’t have caught 90% of what he did that night if I’d been there.”

“90% sounds a bit optimistic.” He winked. “First problem you would have had that night if you approached it like the first time you heard the album is this: you were trying to ‘understand’ what you heard. Somewhere around listen #50, or so, you ceased with the cognitive bullshit. You let the music in, unfiltered, to work its evocative emotional magic that is at the root of musical experience. Chaps my ass when I hear people say: ‘I don’t like jazz… I don’t understand it.’ What in hell are they trying to UNDERSTAND?”

He looked at me for my answer. I just shrugged. I didn’t know what I had been trying to understand before listen #51.

“You need to understand something else about your audience and yourself. Because of recordings and radio and all the other in-your-control listening opportunities, your musical development has been culturally stunted. It’s so easy to tune that dial to the lowest common denominator. Before you know it, you’re tapping your foot to The Monster Mash. If you had been lucky enough to catch the opening night for Beethoven’s Fifth, you would have had no previous performance to measure it against. After that night, it is unlikely that you would have ever heard it again. But a listener from ‘then’ would’ve ‘gotten’ it. We can read the performance reviews. They got it with one listen. Some of the reviewers became quite eloquent in their condemnations of his… ah, symphonic vision. But even the bad reviews are detailed and specific about what happened that night. But like it or not, if you weren’t there, it didn’t happen.”

He looked at the keyboard gathering his thoughts. “To enter into this discipline of improvisatory music; jazz, if you like, you and I have a lot of things we need to do at a cognitive level. But as long as the theory I teach is processed cognitively as you perform, you can’t really blow. As long as the technical demands of the instrument limit your ability to express, you can’t blow.”

He let the silence settle for a moment. “You can see the attraction of drugs or alcohol. Some players fall into substance abuse because it turns off that cognitive thing. Unfortunately, some of these pop jackasses forgot to learn how to play before they got high. More unfortunately, some master improvisers got high to throw the learning to the wind so they could really cut loose with ferocious musicality. Tragically, many found a double-edged sword in that choice.”

As our time that week drew to a close, he left me with this truth: “Most people in that club in Toronto didn’t get it either. Most people in a concert hall only serve as seat-warmers.” He could get really cynical about the audience. A residency gig at the Playboy Club’ll do that to you. “Funniest thing, if Jim was really on that night, and it sounds to me like he was, Jim was just an available conduit for the music. He played in a groove of musical availability that he’d spent a lifetime channelling. If you like New Age process labels. Anyway, I’m pretty sure Jim didn’t ‘get’ any of it… at all… until he heard the playback later on the bus. Oh yeah, one more thing: you can only listen to a live album once, after that you’re just listening to reinforce an echo of something that you probably already missed the first time. Don’t waste a ‘first listen’ again by trying to understand what you’re hearing.”

In the twenty-some years since my last lesson with John, I still find myself working on what he called my ‘stunted cultural growth’. Unless I’m working on a tune, I try to only listen to music I’ve never heard before and probably won’t hear again. An easy resource for that in my life has been jazz radio stations, but to suggest that to others gets me back into that argument about labels. But I can suggest an easier alternative that leaves the choice of musical label if you’re still into that. Up to you:

GO SEE LIVE MUSIC!

I’m not talking about your big arena shows. Don’t miss a good one, if you’re a fan of musical spectacle (I am), but search out the local club scene. Play 19th century once a month; go get the air in your ear vibrated by a real human. Live music offers a tender caress to your ear that can rival the touch of a lover’s tongue.

“At some point in life the world’s beauty becomes enough. You don’t need to photograph, paint or even remember it. It is enough.” –Toni Morrison

Copyright Richard Gibbins, 2019. All Rights Reserved.

“You Can Only Listen To A Live Album Once” was originally published in C.R.Y on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.