A Family Library

The Influence of a Father’s Library

by Ken Pierpont

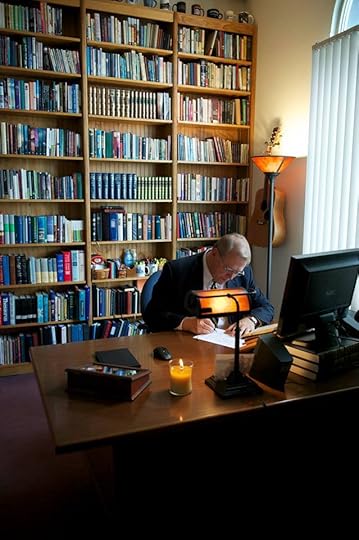

Two years

ago I walked for the first time into the rooms in our church that would become

my study. The inner room had French doors, a beautiful arched window, and

eleven-foot ceilings. I immediately imagined floor-to-ceiling bookshelves

lining the walls. Shortly after our arrival the men of the church began to turn

my dream into a reality. Now I spend hours every day in those rooms. I often

instruct my children, counsel others, meet with the staff, study for messages

and write there among my treasured books. Every week I worship God and pray in

the quietness of those book-lined rooms. A personal library is a wonderful

thing.

I have an

Amazon Kindle. It is a clever gadget, but I cannot imagine any electronic

reading device replacing the pleasure of a book-in-hand or a shelf of books, or

a collection of real books in a personal library arranged in floor-to-ceiling

shelves. I read blogs and write for electronic publications nearly every day,

but I cannot imagine a world without things to pick up in hand and read. I like

having pages to turn. The smell of print, the feel of ragged edged book, or the

weight of a book in hand are pleasures I would not want to be without. I like

real books with annotations in the margins and personal indices in the back.

It is my

abiding desire to influence my children and grandchildren and a major part of

my scheme is to do so with words—with spoken words and with the enduring words

of the printed page. I want my children to cherish good books. Sometimes my

favorite books seem to walk away on their own. Before I call the police I

always go to my son Chuk’s room. I look on his shelves. He has great taste in

books. My very best books often mysteriously migrate to his shelves. Sometimes

I just take them from the shelf and inscribe them to him, and make a mental

note to get another copy. I want the influence of my books to continue long

after I’m gone. Books can be a powerful means of influence.

Charles

Spurgeon has more books in print than any other author ever in human history,

but he had only the slightest brush with the university. He never attended a

single class or lecture. He never enrolled in any college or university, but in

the dark attic room among his grandfather’s books he read. He was influenced profoundly for life by the

puritan books in his grandfather’s dark study. He would be known as the last of

the puritans and the heir of the puritans, because he met the puritans and

spent many, many hours with them in his grandfather’s library. Here is the

account from his autobiography:

But there was one place upstairs which I cannot omit, even at the risk of being wearisome. Opening out of one of the bedrooms, there was a little chamber of which the window had been blocked up through that wretched window-duty. When the original founder of Stambourne Meeting quitted the Church of England, to form a separate congregation, he would seem to have been in possession of a fair estate, and the house was quite a noble one for those times. Before the light-excluding tax had come into operation, that little room was the minister’s study and closet for prayer; and a very nice cosy room, too. In my time, it was a dark den;—but it contained books, and this made it a gold mine to me. Therein was fulfilled the promise, “I will give thee the treasures of darkness.” Some of these were enormous folios, such as a boy could hardly lift. Here I first struck up acquaintance with the martyrs, and specially with “Old Bonner,” who burned them; next, with Bunyan and his “Pilgrim”; and further on, with the great masters of Scriptural theology, with whom no moderns are worthy to be named in the same day. Even the old editions of their works, with their margins and old-fashioned notes, are precious to me. It is easy to tell a real Puritan book even by its shape and by the appearance of the type. I confess that I harbour a prejudice against nearly all new editions, and cultivate a preference for the originals, even though they wander about in sheepskins and goatskins, or are shut up in the hardest of boards. It made my eyes water, a short time ago, to see a number of these old books in the new Manse: I wonder whether some other boy will love them, and live to revive that grand old divinity which will yet be to England her balm and benison.

Out

of that darkened room I fetched those old authors when I was yet a youth, and

never was I happier than when in their company. Out of the present contempt,

into which Puritanism has fallen, many brave hearts and true will fetch it, by

the help of God, ere many years have passed. Those who have daubed up the

windows will yet be surprised to see Heaven’s light beaming on the old truth,

and then breaking forth from it to their own confusion.

Thomas

Edison was born in 1847 in the canal town of Milan, Ohio. He was the baby of

seven children and he only attended school briefly. He was taught at home by

his mother with the use of his father’s library. Paul Ford was a well-known and

widely read historian. As a child he was often sick and educated by having the

free run of his father’s library. Jonathan Edwards, a colonial preacher, was

one of the greatest preachers and philosophers in America. He was profoundly

influenced by his own father’s library. J.

Hudson Taylor, the great pioneer missionary to China, was converted while

reading on Sunday afternoon in his father’s library. Loisa May Alcott’s main literary source was

her father’s library. Virgina Wolfe said, “I owe all the education I have ever

had to my father’s library.”

Theodore

Roosevelt wrote of his home: “At Sagamore Hill we love a great many

things—birds and trees and books and all things beautiful, children and gardens

and hard work and the joy of life. The place puts me in the mood for a good

story. Of course, I am always in the mood for a good story. Perhaps that is why

I am rather more apt to read old books than new ones. And perhaps that is why I

surround myself with reminders of stories, long ago told, or those yet to be

told. Life ought to be redolent with the stuff of life from which the stories

of life inevitably spring.”

Doug

Phillips has written with warm affection about his father’s library. “The mere

presence of my father’s library taught me to respect and love important books.

And it increased my respect for my father as a man. My father had chosen not to

invest his limited and precious resources in sports paraphernalia or

entertainment, but in documents, literature, and resources that filled our home

with knowledge. In my father’s library, I met and grew to love the men that my

father respected.” Mr. Phillips wrote:

“To this day, when visiting a friend’s home, I love to be invited to look at

his library. I can tell so much about the man by looking at the books he has collected,

how he prioritizes them, and whether they are unopened museum pieces, or

well-worn, dog-eared tools of dominion.”

My own

father took me to many, many libraries through my growing up years. He loved

books and he was frugal, so a library is a great place for a frugal

bibliophile. On Saturdays in the fall we loved to follow college football, but

not before we had wandered among the stacks in the old Kregel store in Grand

Rapids, Michigan. The entire basement housed a huge collection of used

theological and devotional books. Eventually Dad acquired a significant

collection of books. I have spent many, many hours browsing and reading and

learning—having my curiosity aroused by those titles and learning to cherish

books.

A few

years ago I was invited to speak to an annual gathering of an organization that

is in decline. It was a delightful meeting but my family nearly outnumbered the

attendees. But it was on the beautiful west coast of Michigan and when the week

came to an end I had met new friends and found some fresh peaches by a roadside

stand and spent a good week with two of my sons. On the way home we would meet

another of my sons in Grand Rapids and then, before leaving town, we would

always browse the stacks in the used book shop. There I discovered the complete

works of Henry VanDyke, many years old and in nearly “mint” condition. I

happened to have set aside a bit of money in my discretionary account and now

they grace my shelves and often delight me with their poetry, prose,

description, narration, nature, and devotional writing. They outlasted their

writer. They outlasted their original owner and they will outlast me. One

winter evening many years from now a young man longing for adventure could sit

before the fire and pass his eyes over the very lines that made their way into

my own soul. That young man or young woman may be my grandchild. My choice of

books is one of the tools of enduring influence at my disposal.

In Shelden

VanAuken’s poignant telling of his young life and love in A Severe Mercy he writes of revisiting Glenmerle in the night. It

was his boyhood home. Among the rich memories that wash over him in the

moonlight are memories of books that opened the world to him. In the same way

his own story has given us a view of the world we could never have otherwise

had—a view of Virginia, of sailing trips, and of Oxford, of misty cobblestone

streets and quiet conversations with C. S. Lewis and friends, considering the

truth of God.

John

Maclead wrote: “It is an old and healthy

tradition that each home where the light of godliness shone should have its own

bookshelf. Blessed is the man or woman who has inherited such a cultural and

spiritual bequest.” Henry Ward

Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, said, “A home without books is like

a room without windows. A little library, growing every year, is an honorable

part of a man’s history. It is a man’s duty to have books. A library is not a

luxury, but one of the necessities of life.” In 1815 Thomas Jefferson said, “I

cannot live without books” Even the apostle Paul, while he was imprisoned,

instructed Timothy in 2 Timothy 4:13, “When you come, bring the cloak that I

left with Carpus at Troas, ALSO THE BOOKS, and above all the parchments.”

It interested me to read in the essays of Wendell Berry some comments on reading and education:

“Now to my understanding the simplest and most natural way to educate a child is in a place were a collection of worthy books is near-at-hand. The best place to learn is among people who cherish books, in the circle of your homelight, among stacks of compelling things to read.”

Ken

Pierpont is a pastor, writer, and storyteller from Michigan. He and his wife

Lois have four sons and four daughters who have learned together at home for

thirty years. Ken has written a book, Sunset on Summer, and publishes a weekly

newsletter. For more information visit www.kenpierpont.com.