Exploring Delphi on Paper

In the last two weeks, I've been making some drawings and small paintings of Delphi, trying to explore what made it such a special place for me. What do you do with ruins? We're undoubtedly influenced by all those 19th century travelers to the Middle East and Mediterranean. I saw a lot of them in museums on this trip: here's an example by Jean N. de Chacaton, a view of the Parthenon painted in the mid-1800s.

It's tempting to try to draw the monuments accurately and make pretty travel pictures, especially when the light is so clear and graphic as it is in these places. I always find myself sidetracked in that direction, and it's enjoyable to do detailed drawings and watercolors, or even fast sketches as a record of a place. But sometimes there's something more that feels like it wants to be expressed, and the actual "stones" seem somewhat peripheral to that.

So I started out, as I often do, with a detailed drawing that came before I was even thinking about doing a series. In fact, it was during the making of this first ink drawing that I began thinking about the essence of this particular place and how to express it. But it's often a circuitous route to an answer, and even then, there are multiple possibilities, because a landscape is complex, and so is our emotional response to it. There are physical elements of that landscape that affect how we view it; there is the weather and atmosphere; there are the people we're with, or not; events that happen while we're there -- and there is whatever we bring with us: knowledge of history, reading we've done or things we've been told, or perhaps a completely blank slate; things that happened on our journey there; expectations; the mood and physical state we're in on that particular day. Finally, certain places seem imbued with the events that have happened there and the people who have been there before us. Delphi is certainly such a place. Some people are more receptive to that than others, and that receptiveness may vary with different times or circumstances: arriving at the same time as two noisy busloads of school children is a big difference from being alone at a site.

It's a process to sort through all of that in order to find a personal response and find a way to express it simply and clearly through art, or writing, or any other creative form. A teacher once suggested, when I spoke of my confusion and difficulties with this, "search it out through drawing." I've tried to follow that advice, and I still find the process challenging, but now more fascinating than confusing. Often, as here, I have no clear idea where I'm going at the beginning. By drawing the reality of the subject, I start to edge closer. Certain forms may stand out, or become more important, or perhaps I notice lines in the scene that lead toward or away from each other. I may begin to remember things I had forgotten about how I felt. Recalling the scene through drawing it may tell me something I didn't "hear" when I was there. It is a process similar to a type of dream analysis, where in a quiet meditative state we revisit a dream and the characters who appeared in it, and have a waking conversation with them. When we pay close attention a second or third or fourth time, certain elements drop away as unimportant, and others come to the fore; we begin to identify with certain people or elements. It's also true that whatever answers we get may be partial; a month or a year or even longer may elapse, and then fresh insights might come.

This charcoal sketch came next. Obviously I was starting to hone in one the trees and the way they create a unique vertical punctuation on the side of steep mountains that form a series of interlacing triangles.

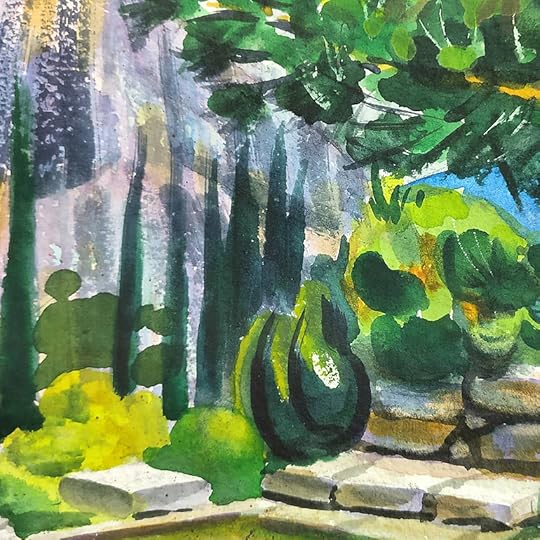

This gouache study followed later the same morning. It crops into the scene in the charcoal drawing to emphasize the trees -- are they cedars or cypresses? -- and adds some minimalistic color. The rocks from the ruin in the foreground are present, but downplayed. I liked this sketch a lot and felt it showed a new direction that could go toward either a print or a painting. That was confirmed when I posted it on Instagram and got an immediate direct message from a friend whose instincts I trust: " I love this." I replied: "It's so...nothing...and yet..." and he responded, "It's all there." Then I asked myself, OK, if "it's all there" -- WHAT have I put there? Old rocks, cedars, mountains, sky. Simple shapes. And what about these non-colors? Why do they work? Because they are harmonious. But in order to figure that out, I had to deviate some more.

Next I used watercolor on rough Arches paper. The full sheet is above, and a cropped detail below that I think is the "real" picture and contains most of what I was aiming for.

I love the saturated color and the freedom of the brushstrokes, for themselves, but the result is pretty unreal for this context.

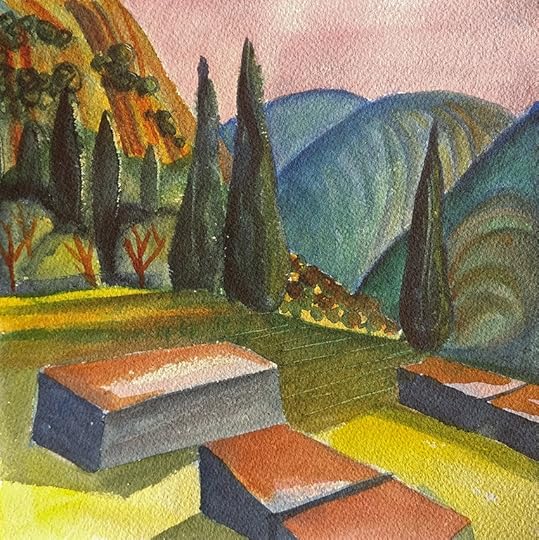

Delphi, I was beginning to understand, was in a spectacular setting on the side of Mount Parnassus, but its overall feeling was very quiet and "inner." That came across better in monochrome or subdued colors, which I used in the next iteration, the gouache above. I was also getting interested in the shapes on the sides of the mountains.

That was followed by another watercolor. I like it, but felt both of these were too pretty and didn't say much beyond that. The full view kept looking like a postcard.

Then I did another bright watercolor, above, from memory, simplifying and stylizing the shapes. This one seems to have possibilities too. Historically, the monuments here would have been painted in bright primary colors - we tend to forget that. A friend who is Greek wrote to me that she liked it a lot: "Beautiful, those light lines on the cypresses. And the expressive colors feel more apt in uniting the landscape with its wild, somewhat extravagant past than the usual soft watercolors which mainly just point out the natural beauty of the Mediterranean landscape."

Finally, last night, I did a brush drawing in ink and indigo watercolor, also from memory. The single, rather Munch-like tree, standing alone, comes perhaps closest so far to my feelings about the place. I also return to that early gouache, and can see better why it works. I'm getting closer, but I'm not finished yet.

What's made the greatest impression on me is the Greek sense of place -- they had an unerring ability to choose particular sites for their cities, and within them, for their temples, theatres, meeting places, dwellings and tombs. I've only understood this by being in those places myself; you simply can't feel that from books or slideshows in art history classrooms. When you are actually there, you see why they chose a particular site: regardless of the centuries that have passed, usually you can still see the view that they saw, feel the wind off the ocean or glimpse the water or a mountain in the distance; you have a sense of what they felt was special or sacred in that place. This uncanny ability to sense what is special about a place, and use it for its full effect, seems equal to me to their architectural skill, or mastery of balance and harmony.

For the Greeks, Delphi was the center of the universe. Kings traveled in person from all the city-states, including the islands, to consult the Pythia, the Delphic oracle in the temple, and they built treasuries on the side of the hill to house part of the spoils won in battle, as a gift to the gods. Mount Parnassus is remote, and far from the sea; at 2,457 m (8,061 ft) it is one of the highest mountains in Greece, sacred to Apollo and Dionysus, and it was also the home of the Muses, who inspired poetry, art, and dance. Delphi is located far up on its slopes. It was a real journey for us to get there, in a modern car, on winding mountain roads. I can hardly imagine what it took for ancient people to make that journey and arduous climb; clearly it was of vital spiritual and political importance to them.

Oracle of Delphi: King Aigeus in front of the Pythia. 440-430 BC, drinking cup, Attic red-figure, Kodros Painter. (Berlin, Altes Museum)

But going there myself, I could see and feel why they thought it was so special. On the way up, we drove hairpin turns, stopping once for a shepherd with his flock of goats, the bells around their necks tinkling, their hooves clicking and scrambling on the loose rocks. We passed through the narrow winding streets of the town of Delphi, perched precariously on the slope, and back into the wilderness to the ancient site, from which you see no signs of human habitation. It's spectacular and wild: from the steep rocky slope with its pines and cedars, you look down across a deep rugged valley. Hawks and owls and crows must have been common then as now, the wind blows, the dark cedars punctuate the sky, and you climb the same paths, past the market and the treasuries, up toward the man temple where the oracle gave her riddles, and even higher to the theatre. Of course, what was once a busy mecca is deserted except for tourists. I tried to imagine a bustling marketplace, smoke rising from sacrificial fires, human voices everywhere: that was difficult. But there was something about the place itself that hadn't tumbled with the stones, and had perhaps even preceded them. Standing on the ridge above the main temple, I tried to imagine coming there any of the grand buildings had even been built. Who were the people who identified this place and first called it sacred? Perhaps what I was seeing and feeling now was closer to what they felt. I kept hearing the cry of a hawk as it circled and rose in the mountain thermals, and then plunged down into the deep valley we can had come from. Above us was snow, the inaccessible realms of the gods. Closer by, in a glade in the woods, near a rushing spring, perhaps the Muses still danced: it wasn't hard to imagine.