A Keeper's Tale, Part 4 of 5:: Hot Herps

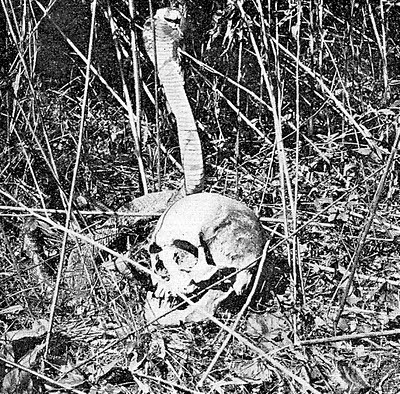

Cantil--a hot herp. Photo by Hodari Nundu

Cantil--a hot herp. Photo by Hodari Nunduby guest writer Hodari Nundu

Salvador took us on a private "tour" of the reptile house,to show us how to feed and handle the different snake species he kept.

Most of them were harmless, but some were extremelydangerous. The most intimidating was without a doubt, the Green Rattlesnake,also known as the West Coast Rattlesnake. Found only in Western Mexico, it iseasily the largest rattlesnake in the country, sometimes rivaling even theEastern Diamondback in size. It is a particularly ill tempered snake, andbecause of its large size, the amount of venom it can inject into its victim isimpressive. Even though, being "hot herps," the rattlesnakes were off limitsfor beginners, Salvador allowed us to join him in the enclosure to show us howto feed them, as long as we stayed behind him.

The snakes weren´t happy to see us. There were several ofthem in the enclosure, and every single one of them adopted an attack postureand started rattling its tail. The sound was amazingly loud, and incrediblyintimidating.

A couple years later, I would read that the effect of arattlesnake's warning sound may be more powerful than we suspected. People whohad never heard it before, and even people who didn´t know what a rattlesnakewas, would become equally alarmed the moment they heard it.

But as intimidating as the rattlers were to my friend and me,they were not particularly scary to Salvador, who had worked with some of the deadliestspecies in the world.

He particularly remembered King Cobras. "They were veryscary" he said "even to an experienced snake handler. Some of them would risetheir heads vertically and look right at our eyes. And they can growl. Theygrowl like a turbine when they're mad".

He also had close calls with mambas and Gaboon vipers. Thezoo where he worked had both species together in the same enclosure. Thekeepers refered to that enclosure as "the terrarium of death."

But although a mamba once slithered up his back and into hisshoulder, forcing him to remain completely motionless for over half an hourbefore the snake decided to climb down, he was never bitten by any of thoseAfrican species.

When I asked him what was the snake he feared the most, hedidn´t hesitate.

"I have kept all kinds of snakes, and I can tell yousomething" he said "I would prefer to work with cobras or mambas anyday ratherthan with lanceheads".

*

The Spanish name for the lancehead snake is nauyaca real,which can be roughly translated as "royal pitviper". Its scientific name,infamous among herpetologists, is Bothrops asper.

It is the most dangerous snake in Latin America, and kills morepeople in Mexico than any other species. It has every trait that makes a snakedangerous: an aggressive, nervous temperament, a potent venom, the habit ofapproaching human settlements in search of rodents, and a proclivity to bitemany times in a single attack, thus injecting huge amounts of venom. In ruralareas where medical attention is difficult to get, most people bitten by thissnake die, and those who survive are left horribly scarred or lose entire limbsto the creature's highly necrotic venom.

There's a legend, often repeated among snake enthusiastsaround here, about a gigantic venomous snake (according to some versions, itwas eight meters long), that was kept in the Guadalajara zoo and managed toinjure or kill three keepers in a matter of seconds.

When my friend and I asked Salvador about this, he smiled.

"It was a lancehead, actually" he said "and it is true thatit bit three handlers within seconds. They were trying to force-feed it, butthey forgot that these snakes can bite even with their mouths closed. The fangsare very long and retractable, so they can stick them out of the mouth. That'swhat this lancehead did; it used one of its fangs to scratch the handler thatwas grabbing its neck. The man released it in alarm, and the snake immediatelyturned in the air at the man grabbing the middle section of its body and bithis hand. When he let go, the snake fell to the ground and bit the third manwho had been holding its tail. It was all over in seconds. All of the handlerslived, but one lost his hand. So in a way, the legend is true. The only partthat was added was the bit about the snake being gigantic".

After this conversation, Salvador showed us how to kill arat to feed it to a snake. Live rodents are rarely given to snakes in zoos;rodents are more than capable of biting snakes and causing them serious injury.This rarely happens in the wild, where the rodent has the much preferableoption of running away. In a small enclosure, however, rodents are no wimps.They will fight to the death to save themselves.

Before continuing I should probably mention that I don´tenjoy killing animals at all. I used to, though, when I was a kid. Me and mycat Pinky (in my defense, it was my sister who named him) would often team upto hunt insects in the house. I would swat the insects and Pinky would eat thecorpses. Whenever we encountered a dangerous specimen, like a scorpion(scorpions kill hundreds of people in Mexico every year), Pinky would replaceme as the main hunter and deal with the creature himself. Somehow, he alwaysmanaged to avoid being stung. Together, we were the perfect pest-managementteam during those rainy months when insects of all sorts wandered into thehouse.

I would also capture insects for a collection I had. I wouldtake the hapless insect and dip it into a jar with alcohol, alive. The insectwould struggle for a few moments before going still. Eventually, I had a smallmuseum of pickled cicadas, earwigs, scorpions and other arthropods, and wouldproudly show it to all my friends until my cat decided that it would be fun tosmash all the jars and spill the foul-smelling contents all over my bed.

This all changed when I was 13, and a mouse wandered intoour house. I immediately went after it, along with the cats. I don´t know how,but I got to the mouse before the cats did, and then, I used a dustpan to beatthe unfortunate rodent to death.

Once it was death, I just sat there, staring at themotionless body. Before that moment, all the lives I had taken had belonged toinsects. It is relatively easy to kill insects. They are small, they don´t havefacial expressions and they usually don´t make a sound when you squish them todeath. Yet the mouse, despite being small, was much more similar to a human. Itbled profusely, and it squeaked in fear and in pain when I struck it with thedustpan.

It made me feel terrible about myself. Had my cats caughtthe mouse, its fate wouldn´t have been much better; Pinky, in particular,enjoyed playing with live mice before eating them. But at least he was meant tokill mice. He was a cat after all. I had no need to kill the mouse. Not in sucha brutal manner, anyways.

That episode got me thinking about death a lot. Even insectcollecting seemed wrong now. Insects, I figured, had naturally short lifespans,and it didn´t seem right to make them even shorter just so I could show theirpickled corpses to people who really didn´t enjoy the sight anyways.

That was the end of my insect-collecting days. Nowadays,whenever I go hunting for bugs, it is with a camera. I must say, getting a goodpicture of a fantastic looking insect and then letting it fly away is much morerewarding than putting it into alcohol.

As for mice, whenever one gets into my house, well, that'swhat cats are for. I just hope they don´t start feeling remorse too oneday.

Next: Hope

Published on November 25, 2011 09:00

No comments have been added yet.