Adam Phillips on creativity and mental health

BY CATHARINE MORRIS

The psychoanalyst and writer Adam Phillips was interviewed by Joan Bakewell at King's College London on Monday as part of the Royal Society of Literature's autumn programme. According to the blurb, he would reflect on relationship between creativity and mental health; on whether we try too hard to be happy; and on his notion of psychotherapy as a kind of practical poetry.

Psychoanalysis is closer to poetry than it is to science, he said: people undergoing analysis, like poets, are attempting to be as articulate as possible about the things that matter most to them, and it is often during that attempt that they discover what they think and feel. Freud may have been disappointed that his Studies in Hysteria lacked "the serious stamp of science", but Phillips is comfortable with the idea of psychoanalytic theory as a set of stories. As the editor of a new Penguin edition of Freud, he heeded Bruno Bettelheim's complaints about the loss in the standard English edition – translated by James Strachey – of Freud's accessible, literary quality, and set out to restore it.

Phillips told us that he decided to become an analyst after he read Carl Jung's autobiography, and chose child psychoanalysis in particular because he thought it would be "more fun". (He thought that his colleagues would be more fun, too; he emphasized that this was not the case.) He talked about his admiration for Donald Winnicott; about modern parenting ("It has become a cross between a middle-class religion and a science – a terrible combination"); and about children in literature – it was in the early nineteenth century, he said, that people began to see childhood as important and significant, and to appreciate the extent of what children can intuit about adult life. He was also asked about kindness, the topic of one of his books – there is a fear attached to one's instinct to be kind to other people, he said, because acting on it means becoming involved in their lives.

These were all interesting topics, but the conversation never turned to creativity and mental health, as many in the audience were no doubt expecting it to. The evening was sponsored by Richard and Jenny Davenport-Hines, whose son Cosmo took his own life after suffering symptoms consistent with schizophrenia. They provided a moving statement about him and about his original use of language, which seemed to decline or lose focus as his illness progressed.

The relationship between creativity and mental health has been much studied. In the TLS of September 2, Gregory Currie wrote that "the long-standing notion that creative people are mad or close to madness got some support from a mid-1990s study of creative groups which found that only one of fifty writers (Maupassant) was free of psychopathology, and that this group contained the highest proportion of individuals with severe pathology (nearly 50 per cent) compared with scientists, statesmen, thinkers, artists and composers"; he also said that there was "a reasonably well-evidenced relation between creativity and milder forms of schizotypy and bipolar disorder". But it is a rather fraught subject. For one thing, what is creativity, and how does one measure it?

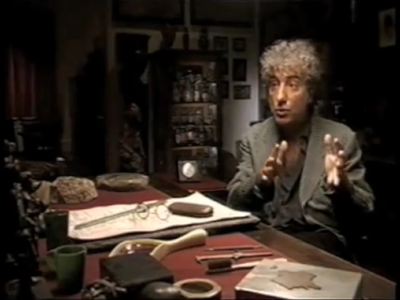

Phillips himself has explored this topic in a television programme, in which he comes to the conclusion that we romanticize a link between creativity and mental illness, partly as a way of explaining away marked talents that we lack ourselves. In that programme he interviews Gwen Adshead, a consultant forensic psychotherapist at Broadmoor Hospital; she says that there are people for whom "something about their imagination seems to have been liberated by their mental illness" – they may be more prepared "to think outside the box . . . to see things differently from how most people see things".

But she also says that the link between mental illness and creativity has been somewhat exaggerated: "Generally speaking, mental illnesses don't make people more creative . . . . People with mental illnesses have less flexibility in how they respond even to everyday stresses; they have less capacity to use their talents; they have less capacity to regulate their mood and thoughts; less capacity to connect well with other people. They lose things. It's a process of loss". She may be talking about a different sort of creativity from that which we attribute to artists, but the Davenport-Hineses' account of their son suggests that they have seen both sides of that story.

Richard Davenport-Hines published an article about his son on the King's College website earlier this year. He contributed an essay to the book The Death of a Child, edited by Peter Stanford, which was reviewed in the TLS of October 21.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers