(My workshop notes on my method for revising novels, placed here so I can find them again later. Perhaps they'll help you!)

First, FINISH THE NOVEL. This is your most important duty. Just finish. No excuses.

"You can fix a bad page; you can't fix a blank one." – Nora Roberts

Then, dance around for a while! You're done! Put it away and read a good book or two. Come back later.

REVISION (aka The Fun Stuff)

1. Acceptance: everything might change, and that's okay. Keep an open mind.

2. Triage: assessing what needs the most work.

Find your theme (distill your book into 1-4 words. Love heals. The inevitability of loss. Family is chosen.) Print this out—attach it to your computer or somewhere you can see it often.

3. Write your one-sentence elevator pitch.

4. Write your one-paragraph book jacket blurb.

5. Print out and reread your book. (Paper is better for this than reading on computer.)

For every scene, write one sentence about what happens. (Anna arrives home, sees Paul.)

Now is not the time for line-edits—you will make those changes later. If you must, circle things that are wrong, but move through.

For every thought you have about plot/character/setting that must be fixed, make a Post-it note.

6. Mark up the sentence outline with your fix ideas. Ask yourself The Big Questions (see below). Make generous use of the Post-its method (see below).

7. Open the file.

8. "Save As" FilenameCUTS

9. Go back to original; start at first scene.

Ask yourself: Is this scene necessary? Does it do more than one thing (does it advance both plot and character development)? Start late, get out early.

If it is not exactly what you want, CUT it and place in Cuts file. Take what you want to save and move it back to working document, moving forward, sentence by sentence.

Pro-tip #1: At the end of every day, save your document as its name + date (ex: SundayMorning070511) so that you have copies of every day, in case you ever do want to revert or need to save something you cut (you won't, but it helps a writer sleep better).

Pro-tip #2: Every day, when you sit down to work, read over all your Post-its to keep the questions/problems fresh in your mind.

10. Move forward. Ask the same difficult questions of each scene. Is there motion in both internal and external conflict? Are characters growing/changing while acting in a believable manner? Put anything that doesn't work into the Cuts file and start again.

11. Juggle scenes as you come to them. Do not jump ahead. When you have great ideas about scenes to come, use the Post-it method. (It's possible that when you get there, this idea won't be right—don't waste precious time writing it now.)

12. Remember that the beginning is the slowest. While you're not jumping ahead to fix things, you are going backwards as you go, fixing things you've already worked on. But you are merely narrowing your egress. Your revision speed will pick up as you go, until by the end of the book, you'll be flying.

13. On the last pass, concentrate on line edits. This is when you make sentences beautiful, now that you know you're keeping them.

14. The final touches: Put the book into another form (print on paper in a new font, or put it on your Kindle). Read it aloud. Make the little changes. Check POV, grammar, spelling, repetitive words, continuity.

15. Kick it out. Send to your agent, your editor, or start writing that kick-ass query letter. Celebrate. Then start something new.

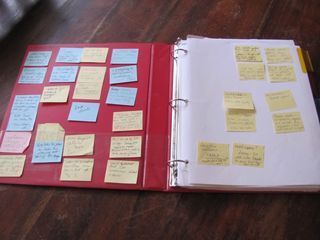

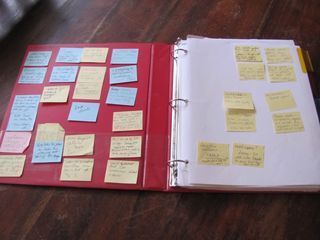

RACHAEL'S POST-IT METHOD

Buy a ton of the small Post-its (you'll want to keep them close and handy, thus the small kind).

For every problem, big or small, write a Post-it. These can range from character problems (Make Nolan more alpha) to plot issues (Add scene with Ollie freaking out).

Attach these to an 81/2x11 piece of paper or into the pages of your notebook, anywhere where you can see them often.

Reread them every single time you sit to work on your novel. Add/move/subtract frequently.

Remember: Big fix-its can fit on small Post-its.

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Using your sentence outline, analyze the plot. Look for holes. Can you clearly identify the inciting incident? The turning points? The black moment? The resolution?

Do internal and external conflicts, goals, and motivations intersect and collide? Are they definable? (If not, consider defining them, so you as the author know exactly what they are.)

Are your characters believable? Individual? Are their goals/motivations/conflicts compelling enough to make the reader keep turning pages?

Are the main characters directly involved in creating/fixing/changing their internal and external plot conflicts?

Can you set your story anywhere else? If you can, make the setting mesh more cohesively with the characters, to make it matter.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Jeri wrote: "Thanks Rachael this was very helpful. I'm almost 1/2 way done editing my book and its truly been hell, so I'm open to any ideas that can make the process easy. I've Wishes & Stitches on the nightst..."

Jeri wrote: "Thanks Rachael this was very helpful. I'm almost 1/2 way done editing my book and its truly been hell, so I'm open to any ideas that can make the process easy. I've Wishes & Stitches on the nightst..."

Jeri, Buena Park CA