New Discussion: Who is YA For?

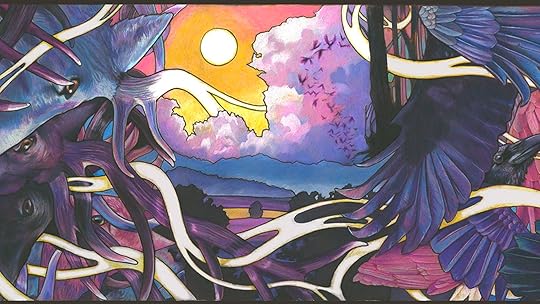

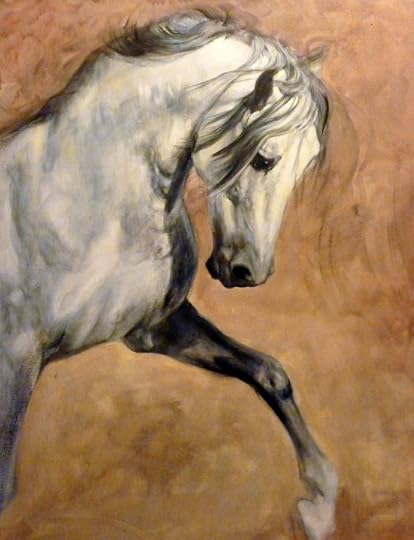

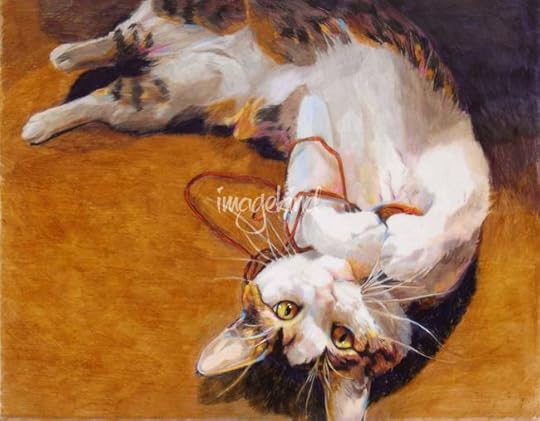

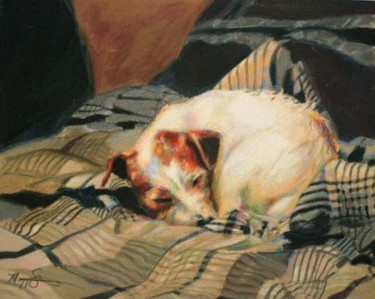

Note: I’ve chosen to feature the original art of Maggie Stiefvater in this post. Please remember to give all the credit for these gorgeous pieces to her.

Extra note: Why Maggie Stiefvater? Other than she’s one of my favorite authors? Well, the fact that she was part of the catalyst of this discussion that started on Twitter a couple of weeks ago. I’ve been thinking about what she and others said, and about the post that really got the ball rolling on this topic.

So, here’s an interesting question: Who is Young Adult fiction actually for? It may seem like a “duh, Captain Obvious” answer — Young Adult fiction is for those under 21 — but the data behind sales, library checkouts, and online reviews proves, no, it isn’t.

The majority of readers of the labeled (and marketed) YA genre in the 21st century are women ages 18 to 45. That’s right. Women with children of their own. And yet…most of us wouldn’t necessarily recommend most YA titles to our adolescents.

Once upon a time, there was something called “New Adult,” a genre that targeted women readers approximately 19 to 30, people who were just starting out on being financially independent, having to manage an apartment or house, an exclusive relationship, and just being a grown-up. “What a great idea!” so many of us currently in that stage of life exclaimed (myself included, as then a new wife and mother). I enjoyed some of those books, sometimes a lot. When you’re about 25, most of us are past the point of relating to your biggest problem being whether to cut math class or not. That was what most YA was like back then.

However, two distinct things happened. One: There was a shift in what NA was, from real plots and discussing relationships and life to little more than pornography (which many readers were not happy with, myself included). Two: YA changed from being about the actual issues teens face to focusing on world-weary 16-year-olds living in dystopian settings that forced them to become the breadwinner or the chosen one or the next queen of the realm.

And this altering of dynamics resulted in some tricky situations. Real high school students ate up The Hunger Games and Divergent and The Maze Runner — but so did parents, for very different reasons. Actual teens were drawn to the escapism of dystopia: it was so far removed from anything they know that it was all about action and adventure and good guys versus bad guys. Parents, on the other hand, considered these series, and others like them, important cautionary tales, for what can happen to our civil liberties and democracies if we get complacent.

So, in the wake of the demise of NA, a new type of “YA” emerged: the kind where any novel featuring a protagonist who was 15, 16, or 17 — regardless of the content, subject matter, or genre — was automatically marketed to real life adolescents.

Many parents do not want their kids reading it. There’s too much profanity, casual alcohol use, cutting school, fornication, and little to no consequences for unwise behavior.

And actual teenagers don’t want to read it, because the wild parties, skipping class on a whim, having sex without worrying, and paying all the bills on time so your irresponsible parent doesn’t forget to sounds like no one they know.

Recently I read a blog post written by a current adolescent, who stated many of these (and other issues) as reasons why she doesn’t read much “YA” anymore. And I agree with her — not as a teen, obviously, but as the mother of a teen who’s having a hard time finding reading material that he can relate to.

And as a mother who’s trying to raise a gentleman, I’m having a hard time finding reading material for him that encourages not swearing, not picking up random girls, and not getting blasted on a Friday night.

(That is a whole post unto itself. Anyway.)

A lot of the issue is this: Publishers saw a goldmine by getting the parents — the people with salaries — to purchase overpriced “YA” novels. Again, who’s mostly reading “YA” these days? Adults. Are kids reading the new releases by “YA” authors their parents are bringing home? Maybe, maybe not.

But here’s the other thing happening while all this is going on: Teens are much more likely to stick with MG fiction, or switch to not reading for fun at all. In English class, they’ll suffer through Shakespeare and the classics, and in their everyday lives, avoid them like the plague. They’ll just check out graphic novels or manga from the library, or skip reading anything and go straight to the movie version.

Is this all teens? No. But is it becoming more and more prevalent and should we be worried about it? Yes.

When I was White Fang’s age (he’s 15 now), YA was just coming into its own. Too many teachers and librarians had complained that kids were expected to leap from Charlotte’s Web to A Separate Peace, and adolescent minds weren’t receiving proper nourishment. So some really smart people decided to create a market specifically for the 14-year-olds who weren’t “into kids’ stuff” anymore, but not ready for highbrow literary analysis.

And there is no denying that series like Harry Potter and Percy Jackson did what seemed the impossible at the cusp of the millenium — they turned kids away from computers and back to books, boys and girls, ages 8 to 18.

Now, though, we’re facing the reverse. And it’s because, once more, publishers are shutting teens out of the market. Kids who have a $10 a week allowance can’t afford $35 new hardcovers. They aren’t going to spend that money on stories that don’t make them feel connected or impacted, anyway.

Authors who write “YA” branded books but are aware their audience is mostly adults can be torn as well. (Enter Ms. Stiefvater’s Twitter thread on the subject.) They want to write about these characters, who happen to be adolescents. They want to write deeper, grittier stories than what you’d find in MG. Do some of them feel they’d be compromising their creative vision by “scaling down” certain things to gear it more towards “real” teens? Yeah, they do. Is that wrong? Hmm. No?

So, what’s the solution?

Well, here are my ideas: We need to go back to writing and publishing a market that teens can relate to and learn from. We also need to be aware there are plenty of adults who want to read fun, adventure-filled novels with a minimum of graphic violence and sex and language, and produce more fiction like that — just with 32-year-old protagonists.

And we need to try to drive down the cost of books to begin with — reading will become an elite past-time if we don’t consider the budget of 90% of working Americans.

Maybe we should also stop looking at the almighty dollar as our number one goal, and think more about the expression on someone’s face when they’ve found their next favorite read.

After all, that’s what literature is meant for.

Daley Downing's Blog

- Daley Downing's profile

- 36 followers