Life in the time of T. D’Arcy McGee… by Ann Shortell #History #Canada #Ireland @CelticKnotMcGee

Life in the time of T. D’Arcy McGee…By Ann Shortell

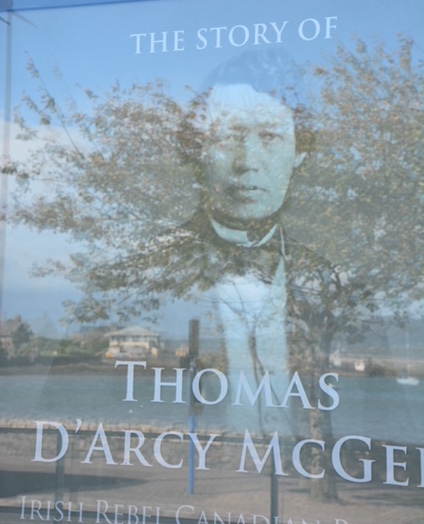

The Honourable Thomas D'Arcy McGee, 1867. Artist: Denis Hurley, (1875 - 1879)

T. D’Arcy McGee is well-known in Canada as one of the Fathers of Canadian Confederation—and as the first person assassinated in this country.

He’s also known and honoured in his birthplace: Carlingford, County Louth, Ireland.

Recently, some close friends visited Carlingford, and lunched at the eponymous bistro D’Arcy’s. Their friendly server, Paul, mentioned that he’s fascinated by McGee, so my friends sent this lad a copy of my novel, Celtic Knot .

I particularly appreciate the book making its way to the town that is also the birthplace of my fictional protagonist, Clara Swift. However, Celtic Knot is a twist of history. My fictional D’Arcy McGee is inspired by the historical figure, but is not a representation of this iconoclast’s life journey.

So it is with this young Carlingford gentleman in mind that I pen a few introductory words here about McGee, that quicksilver son of Ireland and father of Canada.

A photo of McGee’s image in a poster outside the museum in Carlingford, Ireland, captures both the man and the land he loved (photo: Cathy Scott, 2018, used by permission.)

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

The eponymous Carlingford bistro D’Arcy’s (photos: Cathy Scott, 2018, used by permission)

McGee was a constant contradiction of a man: ambitious and self-destructive; compellingly ugly and at times unctuous, while undeniably a charismatic, canny politician and visionary statesman.

He was brilliant, a protean writer of prose and verse, and a celebrated orator. A successful man ever in quest of the right way to live, both for himself and for his people. His swings in mood, thought and political stance proved time and again to be the making of McGee’s fortune, then his undoing. The man charmed crowds and was embraced by their leaders, then lost the support of both—in three countries.

McGee’s intellectual hopscotch wasn’t limited to the political. During the course of his lifetime, he took conflicting positions on temperance and on religion. He began and ended as a prohibitionist and a committed Roman Catholic, but in between came a lifetime struggle with alcoholism and, during his early Irish and American days, a period of strong anti-clericalism.Born in 1825, McGee left Ireland in 1842—not because of economic or political hardship, but due to an adolescent rift with his stepmother. At age seventeen, he stood at a gathering in Boston and spoke with such eloquence about Irish independence that a newspaper offered him a job as their roving representative. After two years, the young McGee returned to Ireland. Though he worked for a time in London, McGee did witness his homeland suffer through the famine.

It’s too harsh to say that McGee viewed one million deaths as a costly harbinger to national revolt. But, in his writings, he did react to the famine mainly in the context of Ireland’s political foment.

Leading up to the 1848 rebellion, McGee morphed from reporter to a central organizer for the Young Ireland movement. When the rebellion failed, he escaped in picaresque fashion and returned to America rather than be captured alongside his peers.

From then on, McGee focused on promoting the status of Irish immigrants. By the 1850s, he turned against America as discriminatory and insular. McGee envisioned a large-scale emigration from America to the province of Canada East, where the British had already granted French Catholics the rights McGee sought for the Irish. His people did not follow; only his own family arrived in Montreal with McGee. There, once again, he quickly became a leading writer, thinker and political force in a landscape undergoing great change.

A decade later, he was the individual who conceived the concept of uniting British North American into a country called Canada. He saw this new nation as a template that could encourage the British to move toward an independent Ireland. McGee’s one brush with armed resistance had convinced him that further rebellion would be the worst possible outcome for Ireland.

This conversion to the concept of an Ireland that would slowly work to regain its rights under British rule placed McGee squarely at odds with old allies. He was not shy about owning his switch in allegiances. In the 1860s, McGee became the most public opponent of Irish Fenian rebels in North America. This endangered his political career, then his life.

McGee was shot in the back of the head on the steps of his boarding house, after a speech defending the founding of Canada. His assassination burnished his popularity. Mere months earlier, he’d been kicked out of the Montreal St. Patrick’s Society, then had trouble getting elected to the Parliament he’d helped create. By the time of his murder, McGee was about to be forced by debt—and having spent his political capital—to accept the sinecure of a civil service appointment. On his forty-third birthday, eighty thousand people took to the streets of Montreal to watch McGee’s funeral procession.

McGee had planned to focus on his writing to reinvigorate himself. As well as his newspaper work and speeches, he’d already authored a dozen books. And he was recognized in his day as a poet of note. Today McGee is almost unknown for his literary works. There is some suggestion that his poetry has been eclipsed in Ireland by his politics.

McGee called himself an old keener. His poem Home-Sick Stanzas describes his decision to leave Ireland as a wound that could not heal. The opening stanza can now be read as an epitaph for this visionary emigrant:

“Twice had I sailed the Atlantic o’er, / Twice dwelt an exile in the west;/ Twice did kind nature’s skill restore/ The quiet of my troubled breast—/As moss upon a rifted tree,/So time its gentle cloaking did,/ But though the wound no eye could see,/Deep in my heart the barb was hid.”

STATUE OF T. D’ARCY MCGEE, PARLIAMENT HILL, OTTAWA ONTARIO CANADA

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Photo by: D. Gordon E. Robertson

Celtic Knot

1868 Ottawa: Irish-Canadian politician D’Arcy McGee is assassinated. Patrick James Whelan is found guilty of murder in a show trial, and publicly hanged. That much is history. Did Whelan do the deed? Clara Swift thinks not. She saw a buggy on Sparks St., moments after the murder. . .

CELTIC KNOT: It’s reimagining a crisis that tested a new nation.It’s history with a mystery.It’s a Clara Swift Tale.And it all begins with a shot in the dark.

“. . .captures the tones and styles of the late 1800s perfectly . . .”

Foreword/Clarion Reviews(FIVE STARS)

“. . . conjures a memorable heroine . . . thrilling . . .”

Kirkus Reviews

“. . . a well-told, gripping tale of murder and its aftermath . . .”

Ottawa Review of Books

Amazon US • Amazon UK •

BookTopia• Watersones

Ann Shortell

Ann Shortell is an award-winning Canadian author. She spent her youth writing serious articles and books about men with power and money, and how they responded to a time of great change in business and politics. Now she’s writing a historical mystery series about a young, poor, powerless Irish-Canadian immigrant girl, forced to cope during times of great trauma and political upheaval. Shortell likes to think she’s evolved.

Ann Shortell is an award-winning Canadian author. She spent her youth writing serious articles and books about men with power and money, and how they responded to a time of great change in business and politics. Now she’s writing a historical mystery series about a young, poor, powerless Irish-Canadian immigrant girl, forced to cope during times of great trauma and political upheaval. Shortell likes to think she’s evolved. She’s a member of the Historical Novel Society, Sisters In Crime, The Writers’ Union of Canada, and a member and director of Crime Writers of Canada (CWC).

Celtic Knot was a finalist for CWC’s 2017 unpublished manuscript award, the Unhanged Arthur.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 16.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #323333; -webkit-text-stroke: #323333} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} span.s2 {text-decoration: underline ; font-kerning: none; color: #295376; -webkit-text-stroke: 0px #295376} p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Published on November 06, 2018 23:00

No comments have been added yet.

The Coffee Pot Book Club

The Coffee Pot Book Club (formally Myths, Legends, Books, and Coffee Pots) was founded in 2015. Our goal was to create a platform that would help Historical Fiction, Historical Romance and Historical

The Coffee Pot Book Club (formally Myths, Legends, Books, and Coffee Pots) was founded in 2015. Our goal was to create a platform that would help Historical Fiction, Historical Romance and Historical Fantasy authors promote their books and find that sometimes elusive audience. The Coffee Pot Book Club soon became the place for readers to meet new authors (both traditionally published and independently) and discover their fabulous books.

...more

...more

- Mary Anne Yarde's profile

- 159 followers