The Lessons of the Great Beaufort Skedaddle

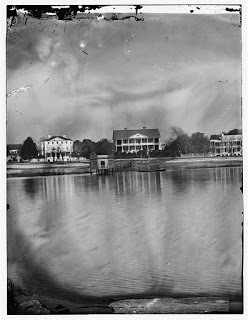

View of Beaufort, SC, Dec 1861

View of Beaufort, SC, Dec 1861The American Civil War can be viewed through many lenses, but a perspective rarely employed is that of the South's refusal to make what was essentially an energy transition--from slave labor to nascent fossil fuels. A small, moneyed elite, who made most of the economic and political decisions for the region, feared loss of wealth. If an orderly transition away from slavery, say over twenty years, had been negotiated between the North and the South, with a gradual introduction of Constitutional rights for former slaves, the great wealth of the antebellum South would undoubtedly have diminished, but much would have remained. Instead, half a million Americans died in war, and the entire South, black and white alike, experienced violence, hunger, and massive destruction of property and infrastructure, to be followed by a hundred years of grinding poverty, during which many of the worst abuses of slavery--racism, segregation, confinement of blacks to the lowest economic strata, black disqualification from voting, and white control of the black population through violence--remained intact. (The decade of Reconstruction was only a partial respite.) Even today, seven of the ten poorest states in the nation are former Confederate states.

Sometimes history plods along slowly. Sometimes it turns on a dime. On the 157th anniversary of the Great Beaufort Skedaddle, it's worth remembering that sometimes doubling down on one's way of life brings about catastrophe from which there is no recovery.

They were at church when the word came. In the pews of Saint Helena’s in Beaufort, South Carolina, master and slave alike heard that an enormous Yankee fleet was massing off Point Royal Sound a mere ten miles away. If Confederate defenses didn’t hold, the town would have to evacuate in a matter of hours. It was time to pack and to pray.

Beaufort antebellum charmIn 1861, Beaufort was one of the wealthiest, most cultured cities in America. The town boasted not only a library of three thousand volumes but also some of the most erudite, educated men in the South. Having built their elegant Greek Revival mansions with ballrooms, chandeliers and two-story piazzas, planter families gathered here each summer to escape the heat and ague of their Sea Island plantations, as well as socialize and talk politics. Secession politics. For more than a dozen years cries for secession had risen from Beaufort, much of them led by its native son, rabble-rousing, fire-eater Robert Barnwell Rhett, remembered as the “Father of Secession.”

Beaufort antebellum charmIn 1861, Beaufort was one of the wealthiest, most cultured cities in America. The town boasted not only a library of three thousand volumes but also some of the most erudite, educated men in the South. Having built their elegant Greek Revival mansions with ballrooms, chandeliers and two-story piazzas, planter families gathered here each summer to escape the heat and ague of their Sea Island plantations, as well as socialize and talk politics. Secession politics. For more than a dozen years cries for secession had risen from Beaufort, much of them led by its native son, rabble-rousing, fire-eater Robert Barnwell Rhett, remembered as the “Father of Secession.”The Confederacy knew full well that Port Royal might be a target for a Northern base, but they couldn’t be sure other sites weren’t also in the running and so were somewhat lackadaisical in establishing defenses for Port Royal Sound. During the summer of 1861, local plantations reluctantly provided slaves to begin construction of two forts to guard the Sound’s entrance: Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island and Fort Beauregard on Phillips Island. But not only were the forts still incomplete by November, the artillery installed fell far short of what was originally proposed and even farther short of what was needed when the Yankees came calling.

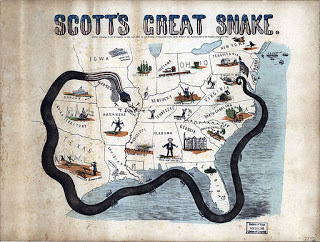

Plans had been underway in the North to take a Southern port since early summer, with Lincoln himself involved in the selection. After all, to implement the “Anaconda Plan”—a tight blockade of the Southern coastline intended to cripple the Confederate economy—U.S. Navy warships needed a place to refuel with the coal that gave them power. Port Royal was one of the choicest deepwater ports on the Southern coast. That a massive Northern fleet was poised to sail was common knowledge to anyone who could read a newspaper once The New York Times published the details in the article, “The Great Naval Expedition,” on October 26th. The only unknown was the destination, a secret that, remarkably, was successfully kept. It wasn’t until they were at sea that the captain of each vessel opened a sealed envelope telling him where his ship was headed.

Plans had been underway in the North to take a Southern port since early summer, with Lincoln himself involved in the selection. After all, to implement the “Anaconda Plan”—a tight blockade of the Southern coastline intended to cripple the Confederate economy—U.S. Navy warships needed a place to refuel with the coal that gave them power. Port Royal was one of the choicest deepwater ports on the Southern coast. That a massive Northern fleet was poised to sail was common knowledge to anyone who could read a newspaper once The New York Times published the details in the article, “The Great Naval Expedition,” on October 26th. The only unknown was the destination, a secret that, remarkably, was successfully kept. It wasn’t until they were at sea that the captain of each vessel opened a sealed envelope telling him where his ship was headed.  The Great Naval Expedition en routeThe fleet that set out on Oct 29thwould prove to be the largest U.S. naval and amphibious expedition in the entire nineteenth century. It included 17 warships, 25 colliers, 33 transports, 12,000 infantry, 600 marines, and 157 big guns. Port Royal, with its two cobbled-together forts supplied with only 2500 men, 4 gunboats, and 39 guns between them, didn’t stand a chance.

The Great Naval Expedition en routeThe fleet that set out on Oct 29thwould prove to be the largest U.S. naval and amphibious expedition in the entire nineteenth century. It included 17 warships, 25 colliers, 33 transports, 12,000 infantry, 600 marines, and 157 big guns. Port Royal, with its two cobbled-together forts supplied with only 2500 men, 4 gunboats, and 39 guns between them, didn’t stand a chance.  Bombardment of Port RoyalNature came to the South’s aid in the form of a storm that sank some of the Northern fleet along the way, and then rough water delayed the day of the final attack. But when November 7thdawned clear and calm, the water so still it was glassy, enough of the North’s warships were available to commence battle. Union ships concentrated their enfilade on Fort Walker. To the soldiers inside, the sound of artillery was deafening. By noon, only three of Fort Walker’s water battery guns were still operational; by 2:30 p.m., all powder was gone. The time had come to abandon the fort. The command at Fort Beauregard, concerned about being trapped on Phillips Island with no line of retreat, quickly followed suit. Thankfully, casualties on both sides were light. Accounts vary, but the Confederates finished the day with between 11 and 59 killed and an equivalent number wounded or missing, while the Union fleet saw 8 dead and 23 wounded.

Bombardment of Port RoyalNature came to the South’s aid in the form of a storm that sank some of the Northern fleet along the way, and then rough water delayed the day of the final attack. But when November 7thdawned clear and calm, the water so still it was glassy, enough of the North’s warships were available to commence battle. Union ships concentrated their enfilade on Fort Walker. To the soldiers inside, the sound of artillery was deafening. By noon, only three of Fort Walker’s water battery guns were still operational; by 2:30 p.m., all powder was gone. The time had come to abandon the fort. The command at Fort Beauregard, concerned about being trapped on Phillips Island with no line of retreat, quickly followed suit. Thankfully, casualties on both sides were light. Accounts vary, but the Confederates finished the day with between 11 and 59 killed and an equivalent number wounded or missing, while the Union fleet saw 8 dead and 23 wounded.Even with the enormous attacking naval force, Sea Island planters had been so confident in the defending forts manned with recruits from their very own Beaufort Volunteer Artillery that many watched the battle from shore on nearby Saint Helena Island. But when Confederate cannons grew silent and cheers reverberated from the Northern ships, they knew something had gone dreadfully wrong. They hurried home to evacuate, no doubt pained to leave bolls of valuable Sea Island cotton still unpicked in the fields.

When news of the battle’s outcome reached Beaufort, a kind of panic ensued. Facing an invading army of Yankees was too dreadful to contemplate; flight was of the essence. But what to take, what to leave behind? The daguerreotypes? The silver? Of course the family bible must be packed. Some loaded up carriages, hoping to stay ahead of the Yankees on the long overland route to safety. But Beaufort was lucky that day—there was a steamer anchored in the river that could take hundreds swiftly to Charleston. However, it had only so much room. Furniture, clothing, horses, and the vast majority of their most valuable property—slaves—would have to be left behind. In the tumult, even food and dinner dishes were abandoned on dining room tables, testament to the haste involved. That evening the steamer departed overflowing with Beaufort’s white citizenry along with every jewel and sentimental item they could squeeze on board. Legend has it that when Yankee forces arrived two days later to occupy the town, they found just one white man remaining in Beaufort, and he was dead drunk.

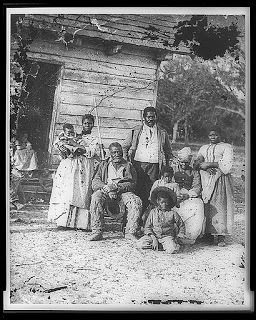

What must the deserted slaves, who spoke Gullah, their own Sea Island patois, have thought as the laden steamer chugged away from Beaufort’s dock? Did they realize that history had unexpectedly turned a corner right in front of them, and that now, after centuries of captivity as a people, they were suddenly free? Perhaps the political ramifications didn’t sink in that night, but before the first Yankees arrived, clothing and other finery had been looted (liberated?) from the grand homes, and food and liquor thoroughly consumed in an understandable celebration of events.

Five generations now free (1862)It is estimated 8-10,000 slaves were left behind in the Sea Islands when the white population fled. They were soon joined by thousands of others who escaped to the region once they realized that Northern occupation meant freedom. They all needed food and shelter, and since the Emancipation Proclamation had yet to happen, their legal status, beyond being “contraband,” was unclear. The Army asked for help and received it in the form of the Port Royal Experiment. Financed and organized by Northern abolitionist charities, the Experiment worked as a test case to create self-sufficiency among the former slaves. Its success points to what Reconstruction might have been if less corruption and more competence had been at its helm. Northern missionaries and teachers flocked to the Sea Islands to create schools and aid societies. Former slaves were allowed to farm the confiscated plantations and were paid $1 per 400 lbs of cotton they were able to harvest. The Penn School on St. Helena Island was one of the earliest schools established for freed slaves and can be visited as part of the Penn Center today.

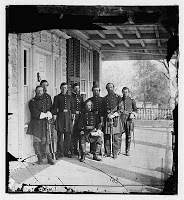

Five generations now free (1862)It is estimated 8-10,000 slaves were left behind in the Sea Islands when the white population fled. They were soon joined by thousands of others who escaped to the region once they realized that Northern occupation meant freedom. They all needed food and shelter, and since the Emancipation Proclamation had yet to happen, their legal status, beyond being “contraband,” was unclear. The Army asked for help and received it in the form of the Port Royal Experiment. Financed and organized by Northern abolitionist charities, the Experiment worked as a test case to create self-sufficiency among the former slaves. Its success points to what Reconstruction might have been if less corruption and more competence had been at its helm. Northern missionaries and teachers flocked to the Sea Islands to create schools and aid societies. Former slaves were allowed to farm the confiscated plantations and were paid $1 per 400 lbs of cotton they were able to harvest. The Penn School on St. Helena Island was one of the earliest schools established for freed slaves and can be visited as part of the Penn Center today. Yankees at home on a Beaufort piazza (1862)The Union Army found Beaufort a pleasant setting for officer’s quarters, administrative offices and hospitals. Because the Army occupied Beaufort until the end of the war, the fine mansions, while suffering damage, were not burned to the ground like so many other Southern towns and surrounding Sea Island plantations. To this day Beaufort’s centuries-old live oaks and antebellum charm remain. Port Royal turned out to be as advantageous a harbor as the Union had hoped and did much to strengthen the potency of the blockade. After the war, most planter families—their sons dead, their plantations burnt, their Beaufort homes sold in government auctions for back taxes (often without their knowledge)—never returned. The civilization that was antebellum Beaufort vanished into the night with that last steamer.

Yankees at home on a Beaufort piazza (1862)The Union Army found Beaufort a pleasant setting for officer’s quarters, administrative offices and hospitals. Because the Army occupied Beaufort until the end of the war, the fine mansions, while suffering damage, were not burned to the ground like so many other Southern towns and surrounding Sea Island plantations. To this day Beaufort’s centuries-old live oaks and antebellum charm remain. Port Royal turned out to be as advantageous a harbor as the Union had hoped and did much to strengthen the potency of the blockade. After the war, most planter families—their sons dead, their plantations burnt, their Beaufort homes sold in government auctions for back taxes (often without their knowledge)—never returned. The civilization that was antebellum Beaufort vanished into the night with that last steamer.It is rare that the wheel of fortune spins as violently as it did on November 7, 1861. The town that had advocated so fiercely for secession was the first to feel the brunt of an occupying army. A people remarkable for their wealth lost almost everything in a matter of hours. A region that so defiantly insisted that its way of life—slavery—was non-negotiable ended up being the first to have a colony of former slaves experiment with what it meant to be free. The Great Skedaddle indeed.

Beaufort 1849 is a novel by Karen Lynn Allen set in Beaufort, South Carolina, at a point when the Civil War might still have been avoided.

Published on November 02, 2018 16:57

No comments have been added yet.