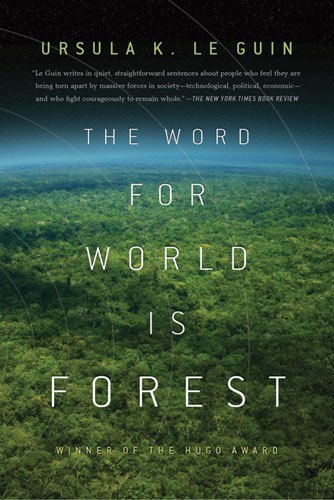

The Word for World is Forest – a retro review

‘As a fiction writer, I don’t speak message, I speak story…’ This is something Le Guin believed, even towards the end of her long and distinguished career. The statement was partly in exasperated response to school librarians and teachers asking her for books with the ‘message’ front-loaded. Philip Pullman, a writer very different in tone than Le Guin but no less ambitious in his grappling with big ideas about the human condition and the nature of reality, has experienced a similar problem. In discussing avoiding didactism in his writing Pullman said: ‘Ideas are best conveyed by making them look not like ideas at all, but events.’ Le Guin, in this slim novel first published in 1972, at the height of the Vietnam War, has tried to do just that – not by offering a polemic, but by dramatizing the problem – the wearily familiar dynamic of an aggressively Capitalist colonial power subjugating and exploiting the indigenous inhabitants for the purposes of extracting the maximum amount of wealth (resources, either in the form of slave labour or mineral wealth, or both), no matter the cost to the ecosystem, its biodiversity, and the lives of the aboriginal dwellers. This rapacious pattern (the inevitable manifestation of ‘progress without limits’, and ‘free trade’, the mantra of late Capitalism, Neoliberalism ) has played out throughout humanity history – although that should not make it normative. We come to think of it as the only game in town, and ‘the way things are’, when, with enough willpower, other ways are possible and other worlds. In Le Guin’s story – set within the archipelago of novels exploring the Hainish universe (an advanced intellectual race who may or may not be the progenitors of human kind) – the author transposes this pattern onto a distant planet. Although it is forgivable to see the echoes of the Vietnam conflict, by setting the action on a richly Tropical planet the human colonists call ‘New Tahiti’ Le Guin creates the cognitive estrangement which defamiliarizes us and makes us see the situation anew. Here, both sides are flawed, moral dualisms become enmeshed in complexity, and the obvious empathic leap, identifying with the diminutive hirsute natives (the Athsheans as the literal ‘underdogs’) starts to feel uncomfortable when we see them enacting ‘war crimes’ against the Colonist just as heinous as those they have endured. The cycle of violence seems inexorable until the arrival of a passing ship from Earth, the Shackleton, conveying Hainish and Cetian ambassadors and an ‘ansible’ (interplanetary communicator) changes the rules of the game. Le Guin’s father was an anthropologist, and her exposure to his discipline and careful methodology informs not only this, but much of her work – yet here it is foregrounded in the figure of Raj Lyubov, a ‘spesh’ (specialist) who has deep sympathies for the Athsheans after learning their language and studying their sophisticated dream-praxis. Yet although Lyubov’s frustrated attempts to ameliorate the brutish treatment of the ‘Creechies’ (as the inhabitants are dehumanised), and wanton destruction of the sylvan biome (the extraction of the incredibly valuable timber drives the ‘annexing’ of the planet) are for a while the main line of desire, ultimately Lyubov is seen as an emasculated protagonist, amid the ultra-machismo of the military endeavour (which Le Guin darkly satirizes: the staccato jargon, testosterone-pumped behaviour, and self-destructing madness mirroring Heller’s Catch-22). As the viewpoint shifts to Selver, the Athshean rebel figurehead ‘god’, it is easy to assume we are going to fall into a classic rebellion narrative – Robin Hood in space; but Le Guin has more sophisticated fish to fry. To say more than that would involve spoilers; but the whole, brief novel (practically a novella) is familiar to movie-goers across the world, for James Cameron Avatar feels like a very loose, unofficial ‘revisioning’ of it. However, those expecting things to play out in a similar way will be deeply surprised. Le Guin is not one to go for the crowdpleasing payoffs. Her universe is more complex than that. In such a short ‘novel’ it is perhaps inevitable that the characters will seem (relatively) thinly-sketched: Captain Davidson, the violent, indignant antagonist, is the least convincing; although there is nothing simple about Mr Lepennon, the Hainish visitor, or the troubled reluctant messiah, Selver. What comes across most authentically amid the ambitious thought experiment of it all (the logical endgame of infinite growth on a galactic stage) is Le Guin’s cri-de-coeur for the protection of precious habitats, the biodiversity of life they contain, and the autonomous rights of those who dwell among them. Environmental awareness was developing when she wrote the book, but it feels increasingly prescient in an age of Climate Chaos and the latest IPCC report urging governments to act now before it is too late. As such, Le Guin’s book is a message in a bottle from the future – but one that interweaves that ‘message’ very skilfully into the texture of the narrative, challenging us as readers: confronting us with our assumptions and complicities. But that is to make it sound abstract and intellectual, when in essence it is an Adventure Story told at a cracking pace. To let Le Guin have the last word: ‘The complex meanings of a serious story or novel can be understood only by participation in the language of the story itself. To translate them into a message or reduce them to a sermon distorts, betrays, and destroys them.’

Kevan Manwaring